Table of Contents

Definition / general | Essential features | Terminology | ICD coding | Epidemiology | Sites | Pathophysiology | Etiology | Clinical features | Diagnosis | Laboratory | Radiology description | Radiology images | Prognostic factors | Case reports | Treatment | Clinical images | Gross description | Microscopic (histologic) description | Microscopic (histologic) images | Positive stains | Negative stains | Videos | Sample pathology report | Differential diagnosis | Additional references | Board review style question #1 | Board review style answer #1 | Board review style question #2 | Board review style answer #2Cite this page: Rytych J, Escobar DJ. Atrophic gastritis. PathologyOutlines.com website. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/stomachchronicatrophic.html. Accessed April 2nd, 2025.

Definition / general

- Type of chronic gastritis characterized by prominent loss of glands secondary to chronic environmental (Helicobacter pylori infection) or autoimmune etiologies

Essential features

- Destruction of glands occurs in gastric body / fundus in autoimmune type and in the antrum in environmental type

- Associated laboratory findings include increased gastrin, decreased pepsinogen I, decreased pepsinogen I/pepsinogen II ratio, iron deficiency and B12 deficiency

- Metaplastic epithelial changes may become dysplastic and progress to gastric adenocarcinoma

- Decreased acid production can lead to enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell hyperplasia and development of well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors

Terminology

- Environmental (metaplastic) atrophic gastritis (EMAG), antrum restricted atrophic gastritis, multifocal atrophic gastritis, type B gastritis

- Autoimmune (metaplastic) atrophic gastritis (AMAG), atrophic autoimmune gastritis, type A gastritis

ICD coding

Epidemiology

- Environmental

- Incidence increases with increasing age; overall worldwide prevalence of ~25%, ranging between 6 and 66% (Ann Palliat Med 2022;11:3697)

- Vast majority caused by H. pylori, which infects more than half of the world population; dietary factors, such as high salt intake, may cause rare cases (Gastroenterology 2017;153:420, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:1133)

- Autoimmune

- F:M = 2 - 3:1

- Average age: 60.3 years (Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;50:1172, Autoimmun Rev 2019;18:215)

- Prevalence: ~1 - 2% in the general population; women and > 60 year olds ~2 - 3% (Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;50:1172)

- Patients have a 3 - 5x risk of preexisting or development of other autoimmune conditions, such as autoimmune thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes mellitus (Autoimmun Rev 2019;18:215)

Sites

- Environmental atrophic gastritis typically initiates in the antrum of the stomach and progressively involves the body and fundus (multifocal)

- Autoimmune atrophic gastritis involves the body and fundus with sparing of the antrum (Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2020;22:38)

Pathophysiology

- Environmental atrophic gastritis is caused by direct damage to gastric mucosa by environmental factors: predominantly H. pylori infection and possibly dietary factors, such as high salt intake (Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:1133)

- Longstanding insults lead to multifocal atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and ultimately gastric cancer (World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:2373)

- Autoimmune atrophic gastritis is caused by the immune mediated destruction of parietal cells (Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6:56)

- CD4+ T cells that are reactive against the H+ / K+ ATPase on parietal cells are the major driver

- These helper T cells stimulate B cells to produce antiparietal cell and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies and activate cytotoxic T cells to damage parietal cells

- Loss of parietal cells results in reduced HCl production and compensatory G cell hyperplasia in the antrum resulting in overproduction of gastrin

- Increased gastrin stimulates hyperplasia of enterochromaffin-like cells (ECL cells), increasing the risk for neuroendocrine tumors

- Damaged gastric epithelium undergoes metaplastic changes, increasing the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma

Etiology

- Environmental atrophic gastritis is directly caused by damage from environmental factors: predominantly H. pylori infection and possibly dietary factors (Gastroenterology 2017;153:420, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:1133)

- Autoimmune atrophic gastritis thought to arise by 1 of 2 potential mechanisms (Autoimmun Rev 2019;18:215)

- Primary autoimmune disease involving antibodies against parietal cells and intrinsic factor

- Secondary autoimmune process via molecular mimicry of the beta subunit of H. pylori urease and the beta subunit of ATPase on parietal cells

Clinical features

- May be asymptomatic

- ~57% of patients report one or more gastrointestinal symptoms, including heartburn, regurgitation, dyspepsia and early satiety (Acta Biomed 2018;89:88)

- Iron deficiency is an early finding secondary to decreased HCl production by parietal cells

- Atrophic gastritis was seen in 19 out of 60 patients with presumed gastrointestinal source of iron deficiency anemia (Am J Med 2001;111:439)

- H. pylori infection is a known cause of iron deficiency (Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:127)

- Pernicious anemia (B12 deficiency) secondary to loss of intrinsic factor production by parietal cells

- Prevalence of 37 - 69% of patients with autoimmune atrophic gastritis

- > 50% of patients with B12 deficiency were positive for H. pylori infection (World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:563)

Diagnosis

- Requires histopathologic confirmation; American Gastroenterological Association Institute guidelines recommend the updated Sydney protocol (5 gastric biopsies placed in separately labeled jars)

- 2 from antrum (lesser and greater curvature) within 2 - 3 cm from the pylorus

- 2 from body (lesser and greater curvature)

- 1 from the incisura angularis

- Correlation with clinical, serologic and histopathologic findings is recommended (Gastroenterology 2021;161:1325)

Laboratory

- Iron deficiency: microcytic anemia

- B12 deficiency: macrocytic anemia, elevated methylmalonic acid (Gastroenterology 2021;161:1325)

- Elevated serum gastrin secondary to achlorhydria due to loss of parietal cells (Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:284)

- Decreased serum pepsinogen I (produced by chief cells) and decreased pepsinogen I/pepsinogen II ratio (Gastroenterology 2021;161:1325)

- Pepsinogen II is produced by pyloric glands and Brunner glands

- Antiparietal cell and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies are commonly seen in autoimmune atrophic gastritis (combined sensitivity ~73% in one study) (Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:459)

Radiology description

- Best evaluated using barium Xray fluoroscopy

- Patchy and mild involvement is not typically recognizable

- Severe atrophy shows a diffusely narrowed stomach that has a smooth contour with loss of rugal folds (Radiology 2008;246:33)

Prognostic factors

- Progression of atrophic gastritis to malignancy depends on severity and extent of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia

- Risk of progression to gastric adenocarcinoma ranges from 0.1% to 0.3% per year

- Risk of neuroendocrine tumor development ranges from 0.4% to 0.7% per year (Gastroenterology 2021;161:1325)

Case reports

- 8 month old boy with atrophic gastritis secondary to Helicobacter pylori infection (Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e17986)

- 28 year old man with seronegative atrophic gastritis presenting as a hemolytic anemia (Case Rep Hematol 2020;2020:8697493)

- 45 year old man with Helicobacter suis atrophic gastritis (Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2022;2022:4254605)

- 50 year old woman with early autoimmune gastritis and characteristic endoscopic findings (Clin J Gastroenterol 2021;14:718)

- 66 year old man with early autoimmune gastritis and a normal endoscopic appearance (Clin J Gastroenterol 2022;15:547)

Treatment

- All patients with atrophic gastritis should be tested for H. pylori and treated, if positive (Gastroenterology 2021;161:1325)

- No established treatment for autoimmune type atrophic gastritis; immunosuppression for symptomatic relief has shown some success in a case report (ACG Case Rep J 2020;7:e00496)

- Patients should be evaluated for anemia and B12 / iron deficiencies and supplemented if present (Gastroenterology 2021;161:1325)

- No consensus on the interval for endoscopic surveillance, American Gastroenterological Association Institute guidelines recommends every 3 years in advanced cases (Gastroenterology 2021;161:1325)

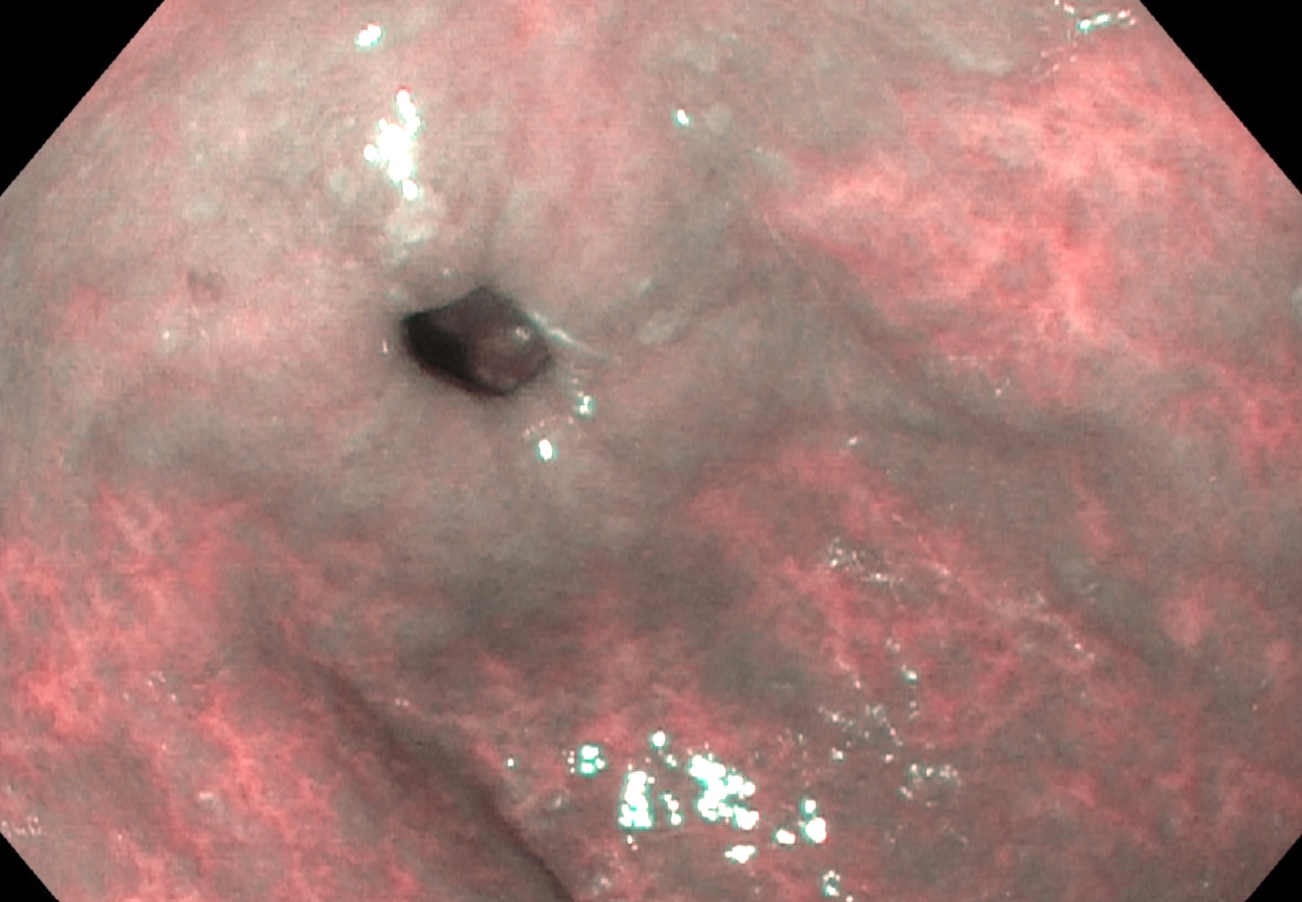

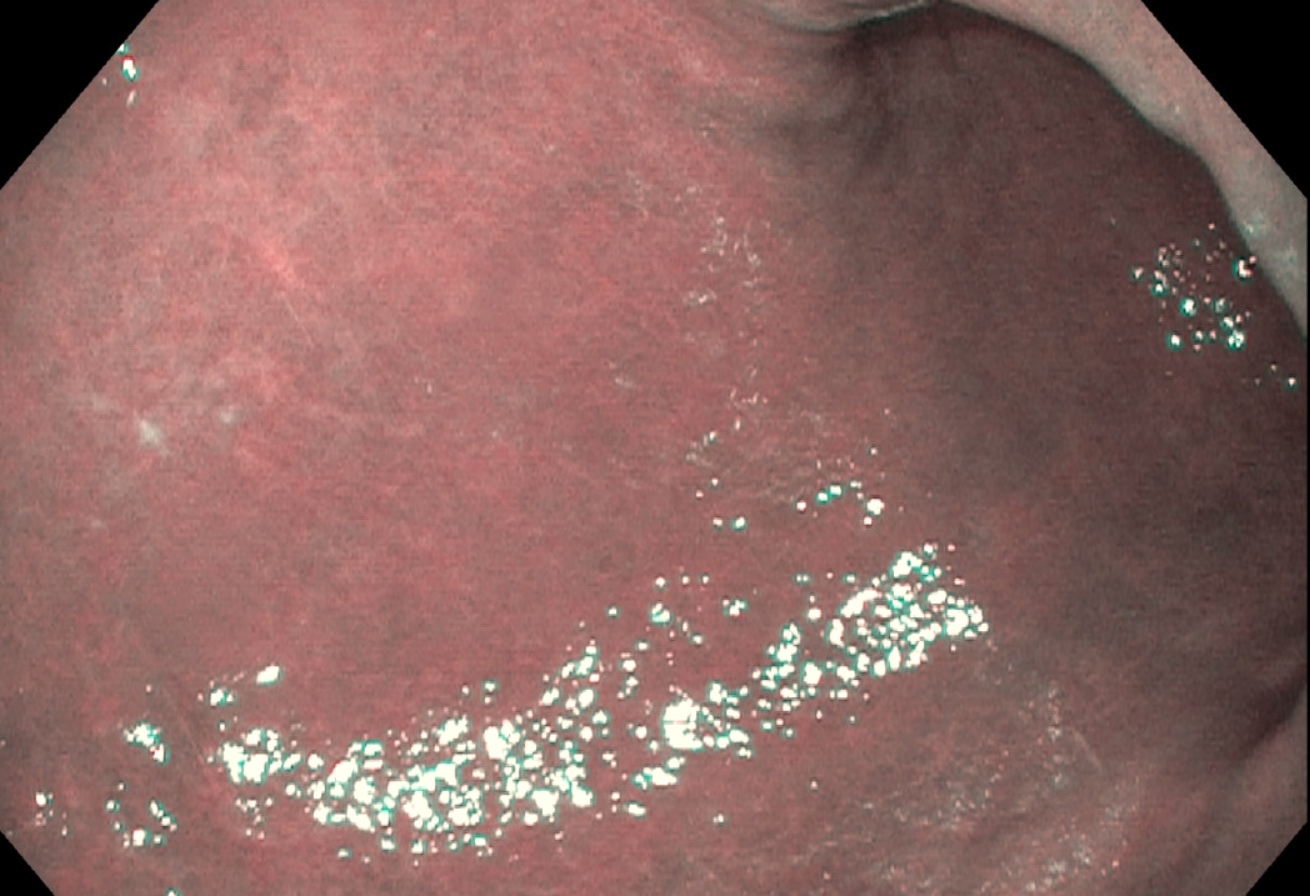

Clinical images

Gross description

- Early atrophic gastritis may appear normal endoscopically

- Typical endoscopic appearance of late atrophic gastritis shows loss of gastric rugal folds and prominent submucosal vessels secondary to the thinning of the overlying mucosa

- Intestinal metaplasia appears nodular and may display the light blue crest sign: blue-white lines seen on the crests of the epithelial surface (Gastroenterology 2021;161:1325)

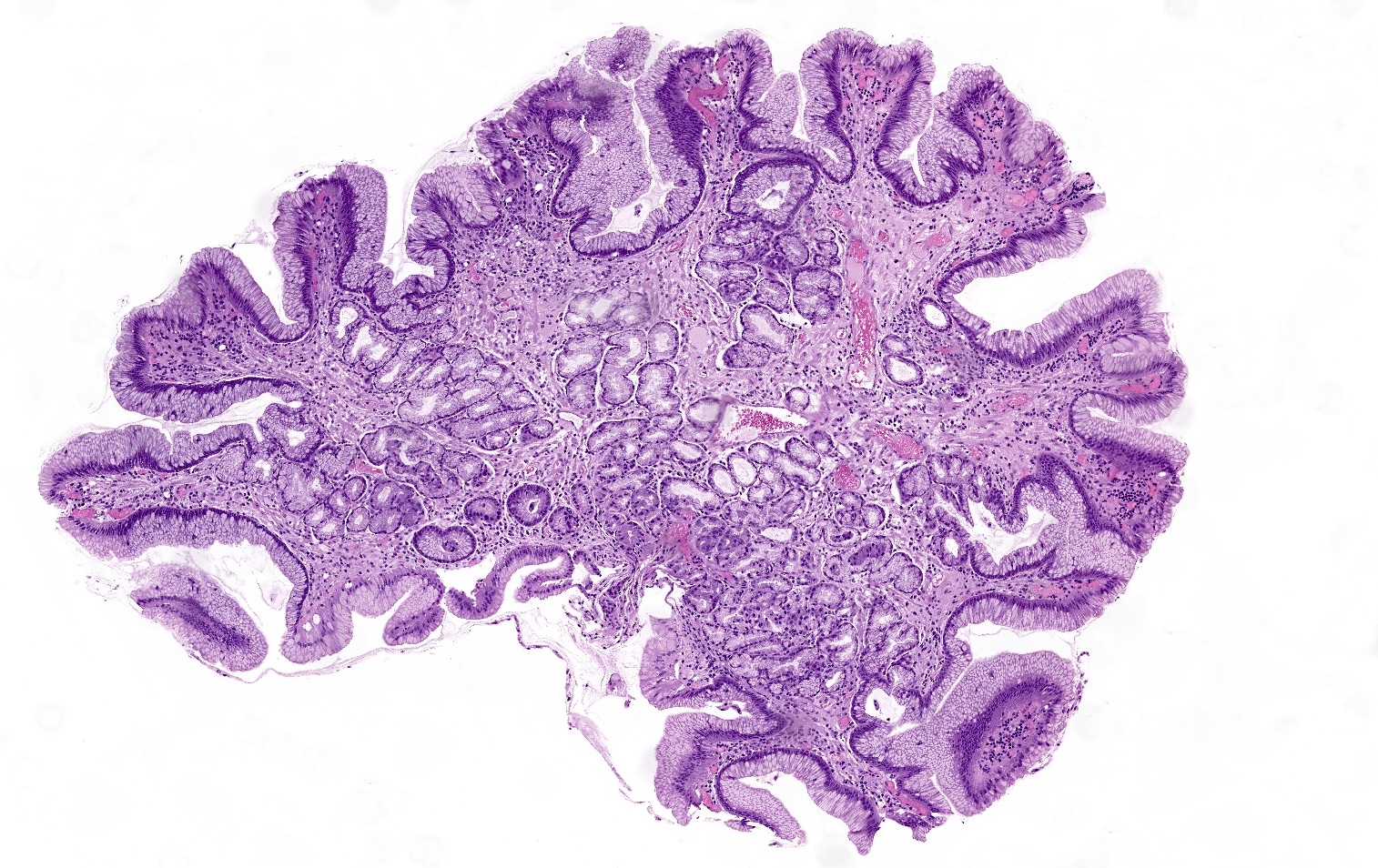

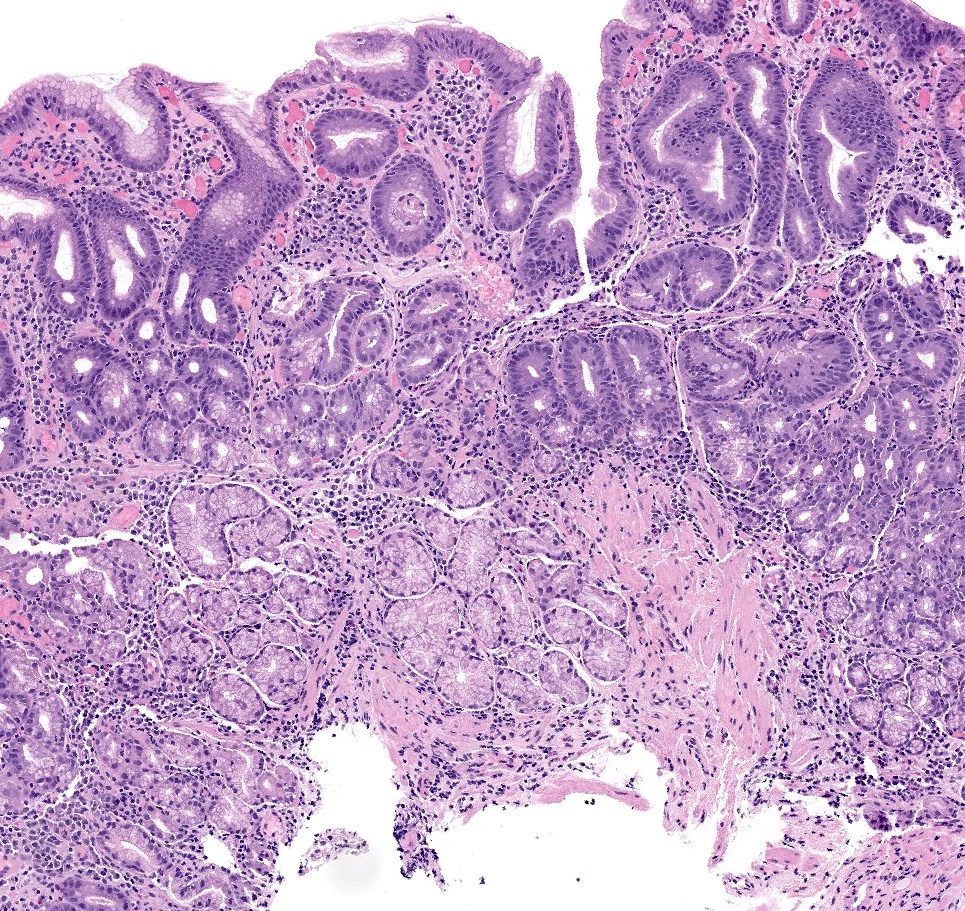

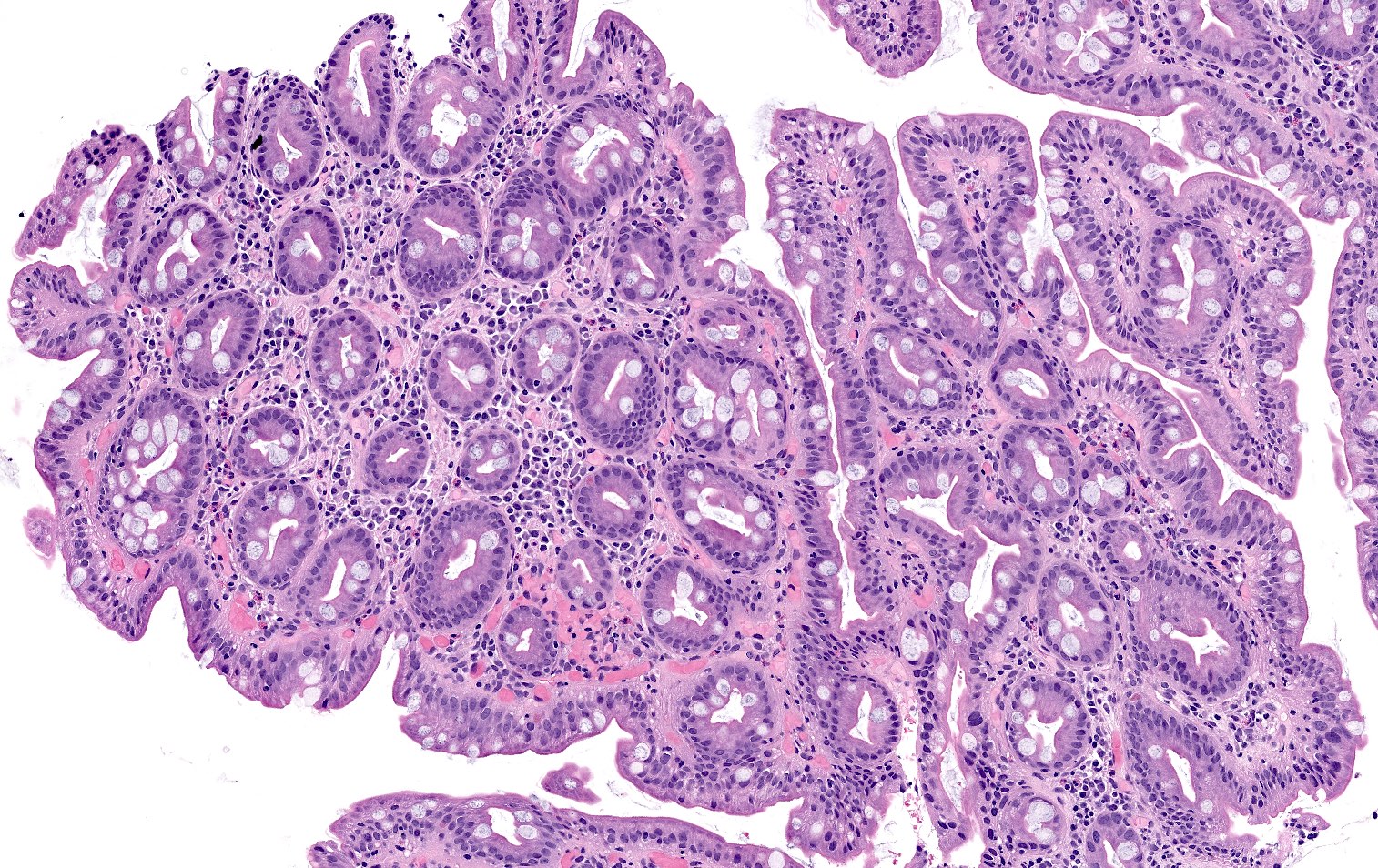

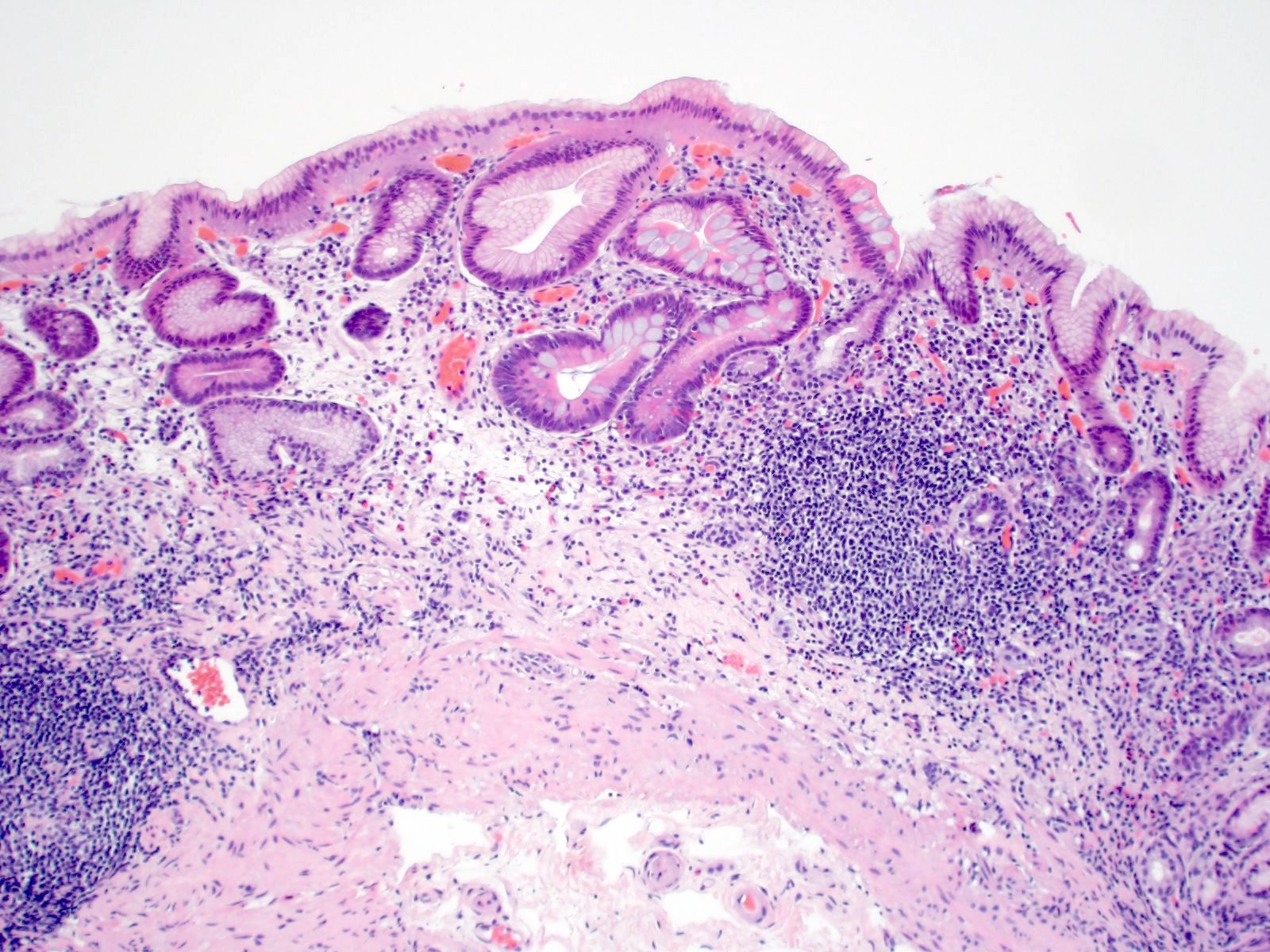

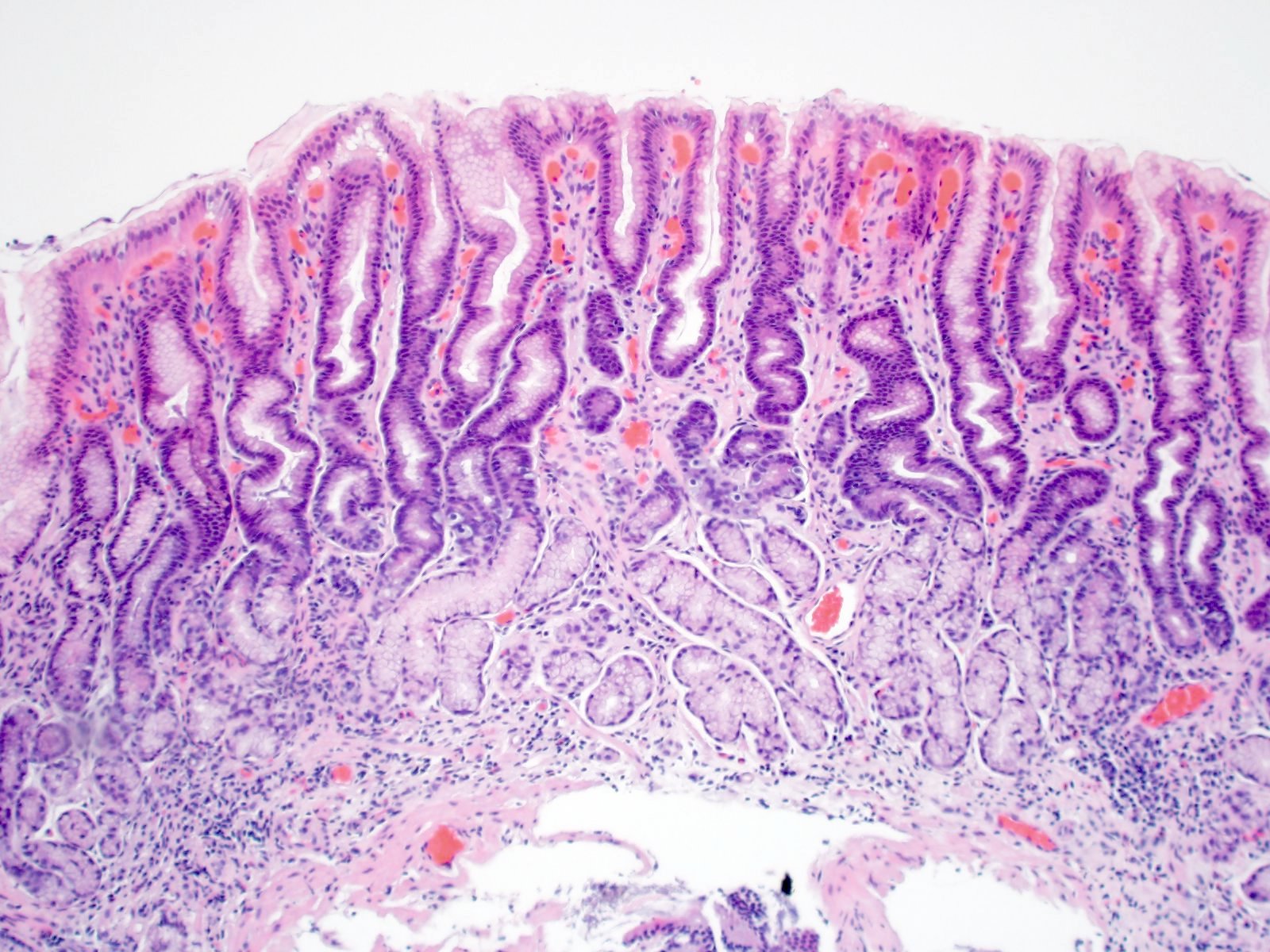

Microscopic (histologic) description

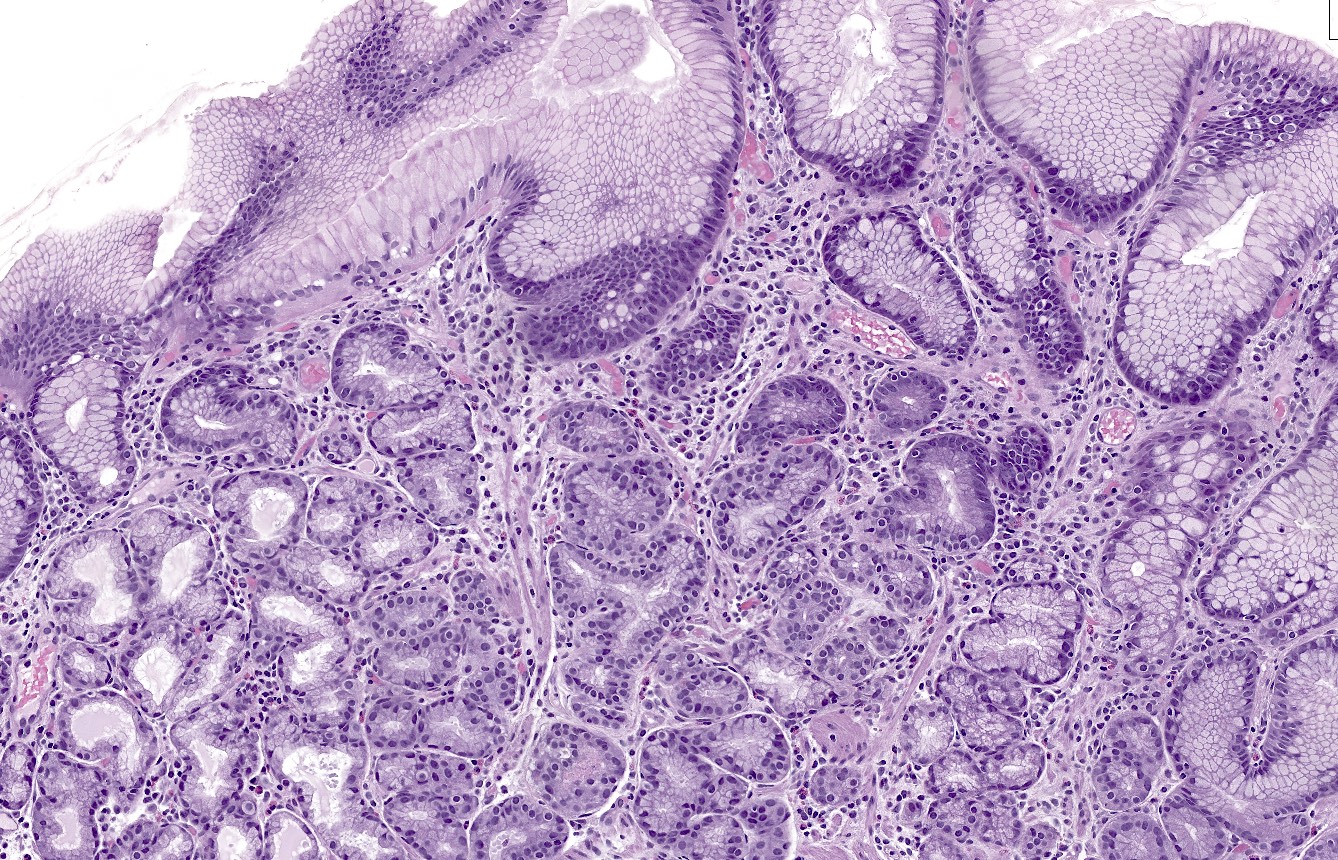

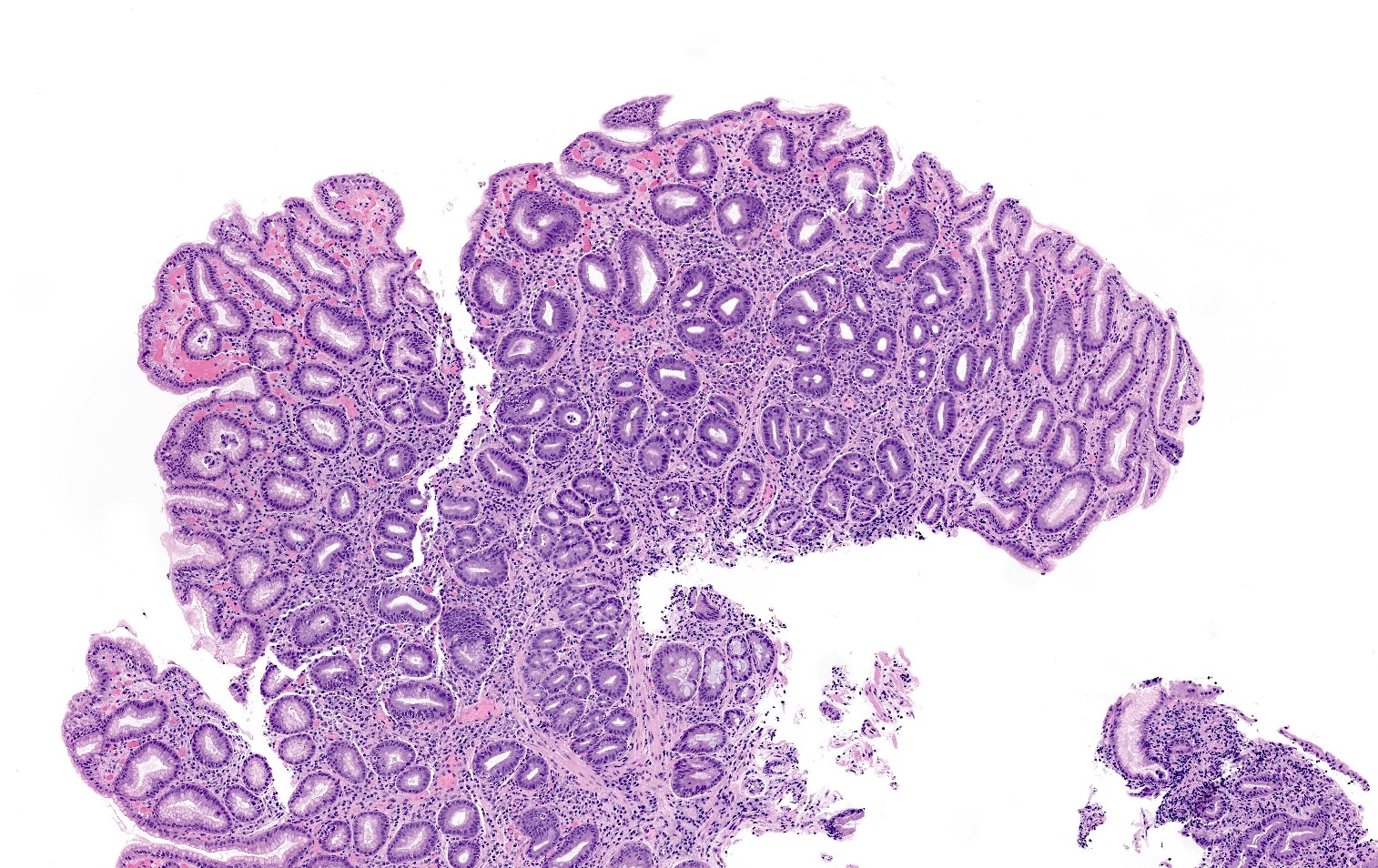

- Atrophy (loss of native glands) of gastric mucosa with lamina propria fibrosis, with or without metaplastic epithelial changes (Dig Liver Dis 2021;53:1237)

- Environmental atrophic gastritis (Arch Pathol Lab Med 2019;143:1327)

- Early chronic H. pylori infections typically contain neutrophils and show a diffuse, superficial infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria of antral mucosa

- Longstanding H. pylori infections show atrophy and pseudopyloric (mucinous) and intestinal metaplasia

- Oxyntic gland destruction is typically less prominent than autoimmune atrophic gastritis

- Enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell hyperplasia is less commonly seen than autoimmune type atrophic gastritis

- Autoimmune atrophic gastritis features differ between early, florid and end phases (Arch Pathol Lab Med 2019;143:1327)

- Early phase

- Mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the basal lamina propria of oxyntic mucosa (bottom heavy)

- Inflammatory cells can include lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils and mast cells

- Lymphocytes may infiltrate glands

- Occasional apoptotic bodies may be seen

- Pseudopyloric (mucinous), pancreatic acinar or (less often) intestinal metaplasia may be seen

- Hypertrophic parietal cells may form polypoid nodules (oxyntic gland pseudopolyps)

- Florid phase

- Marked atrophy of oxyntic mucosa

- Diffuse lymphoplasmacytic inflammation

- Prominent intestinal metaplasia

- G cell hyperplasia present in the antrum

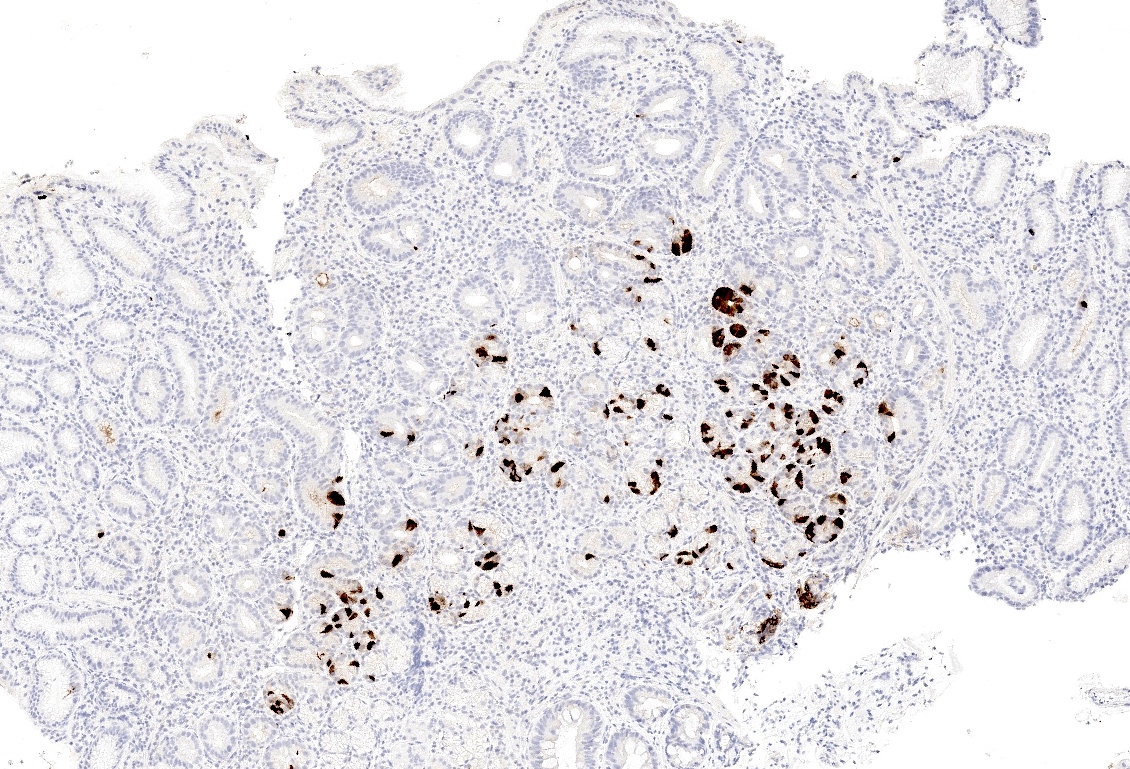

- End phase

- Near complete loss of oxyntic glands and fibrosis of the lamina propria

- Decreased inflammation

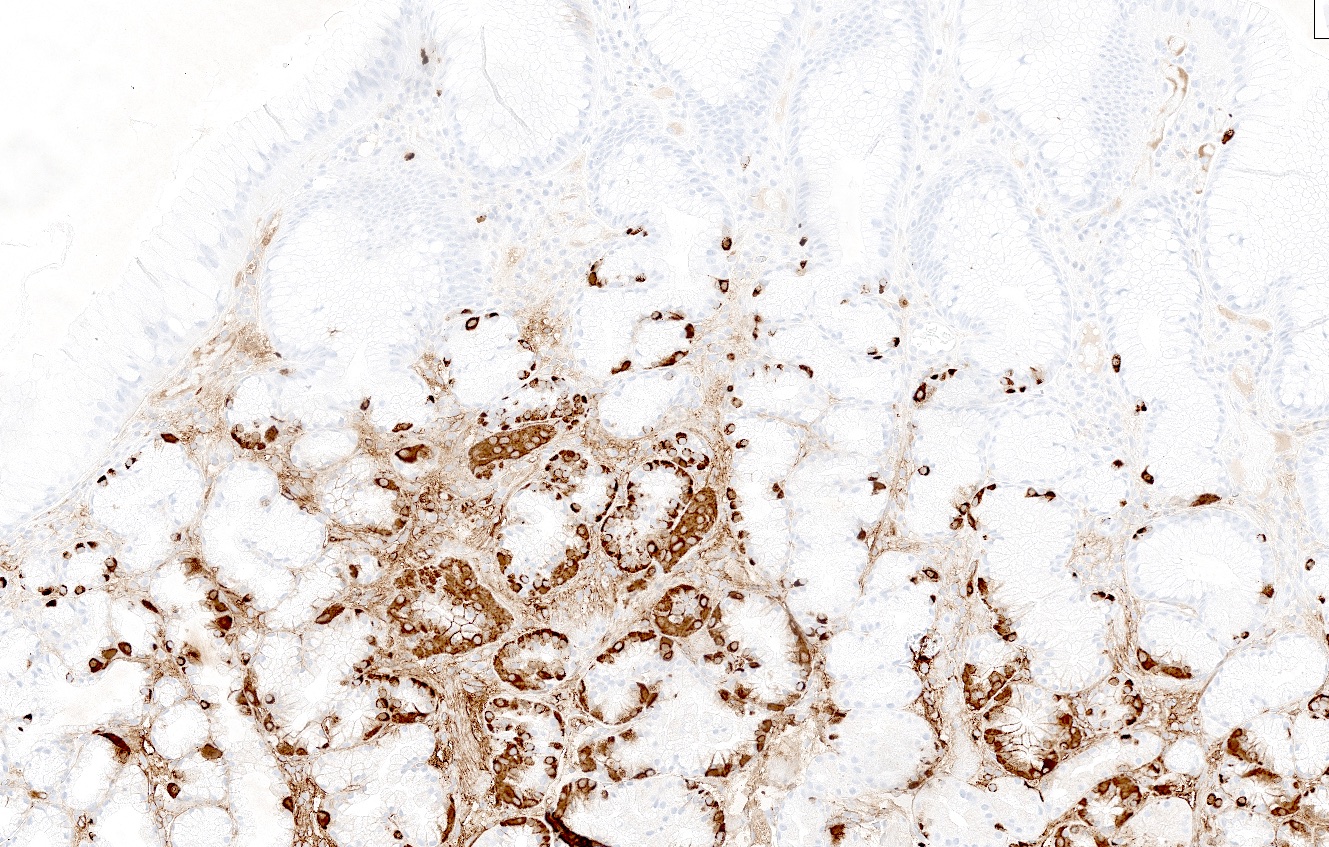

- ECL cell hyperplasia (micronodular / nodular or linear): 5 or more cells forming a nodule surrounded by a basement membrane and measuring < 0.5 mm (micronodular / nodular) / 5 or more cells lining the base of pits (linear)

- Early phase

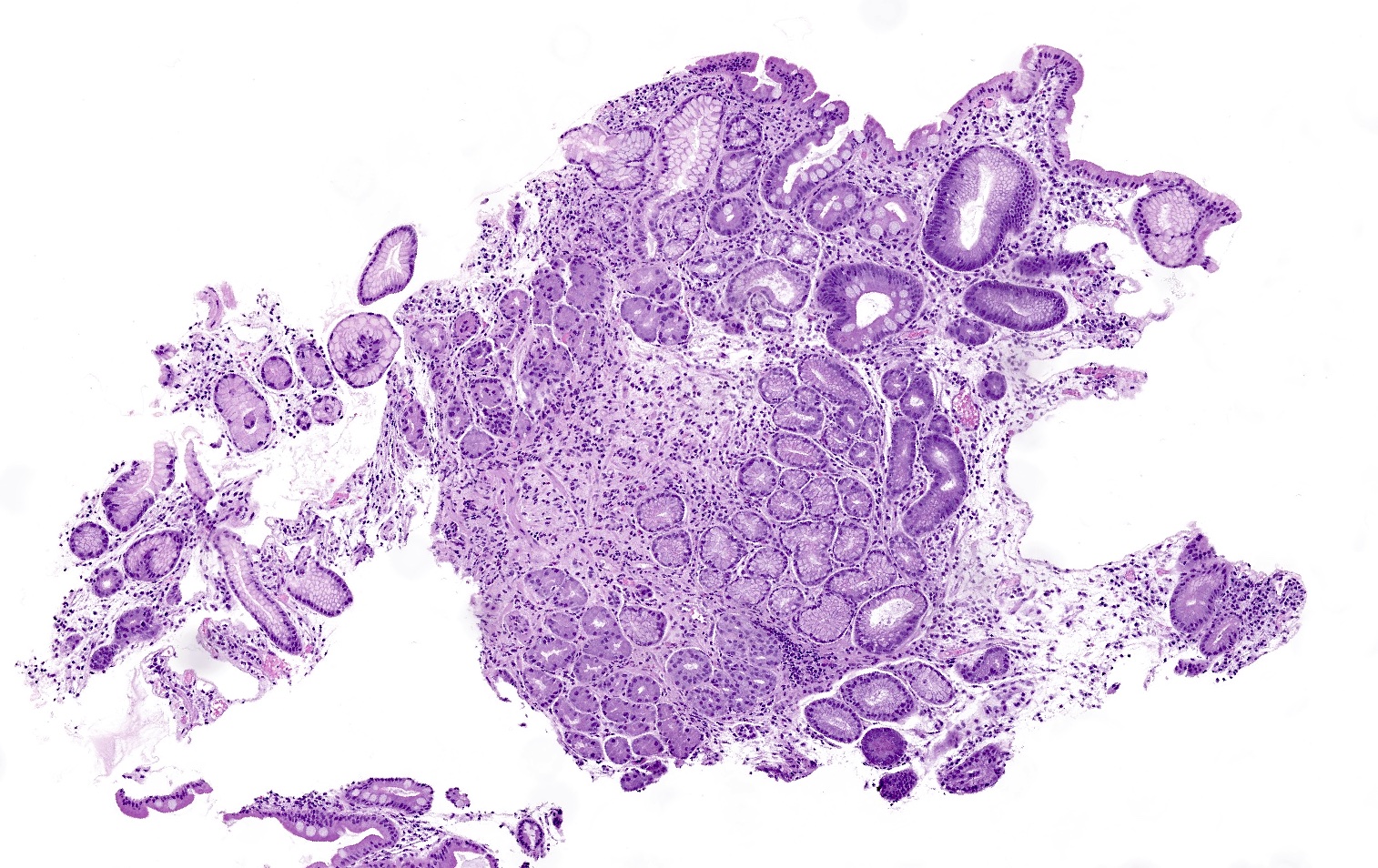

Microscopic (histologic) images

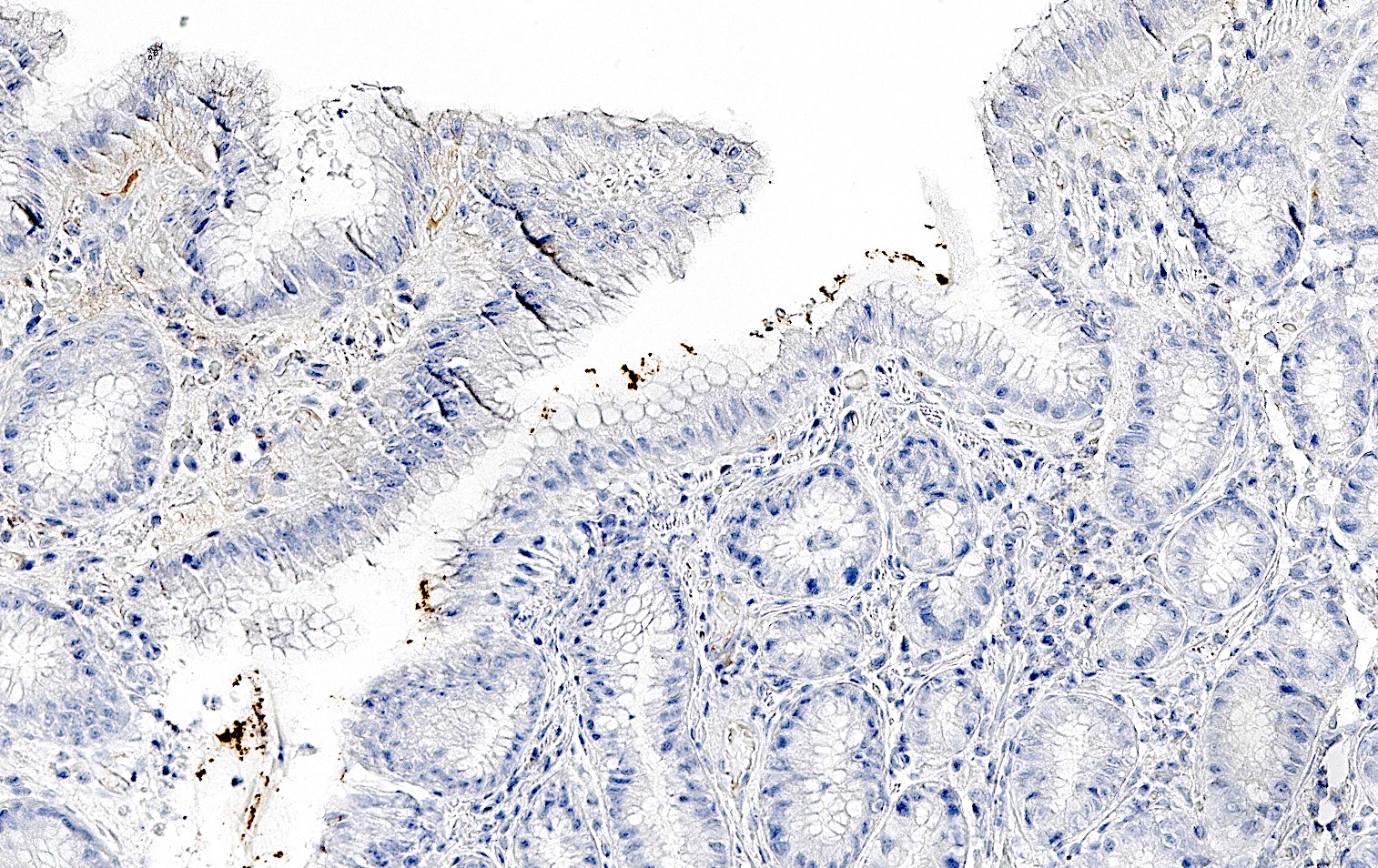

Contributed by Jen Rytych, M.D. and Joshua A. Hanson, M.D.

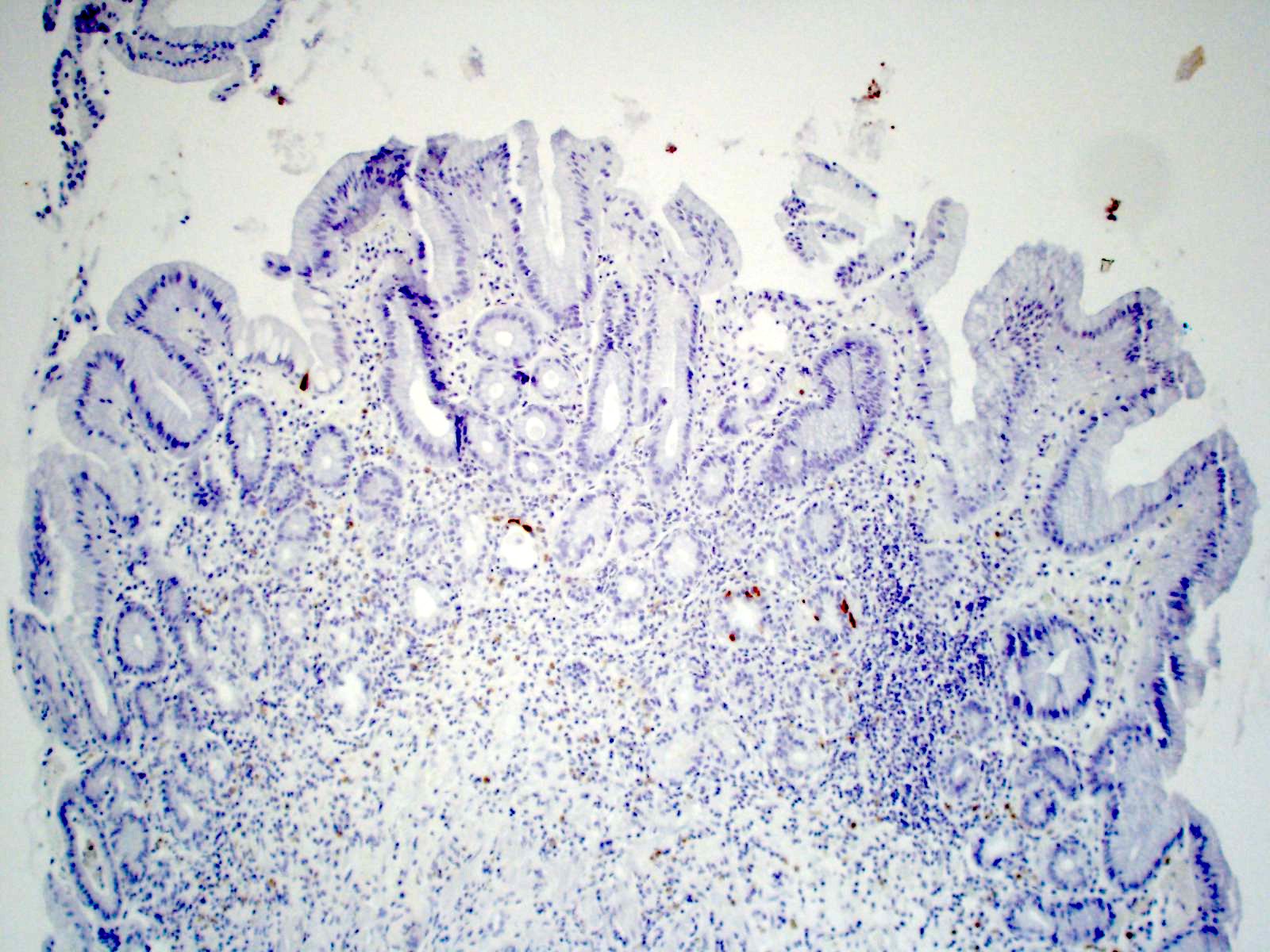

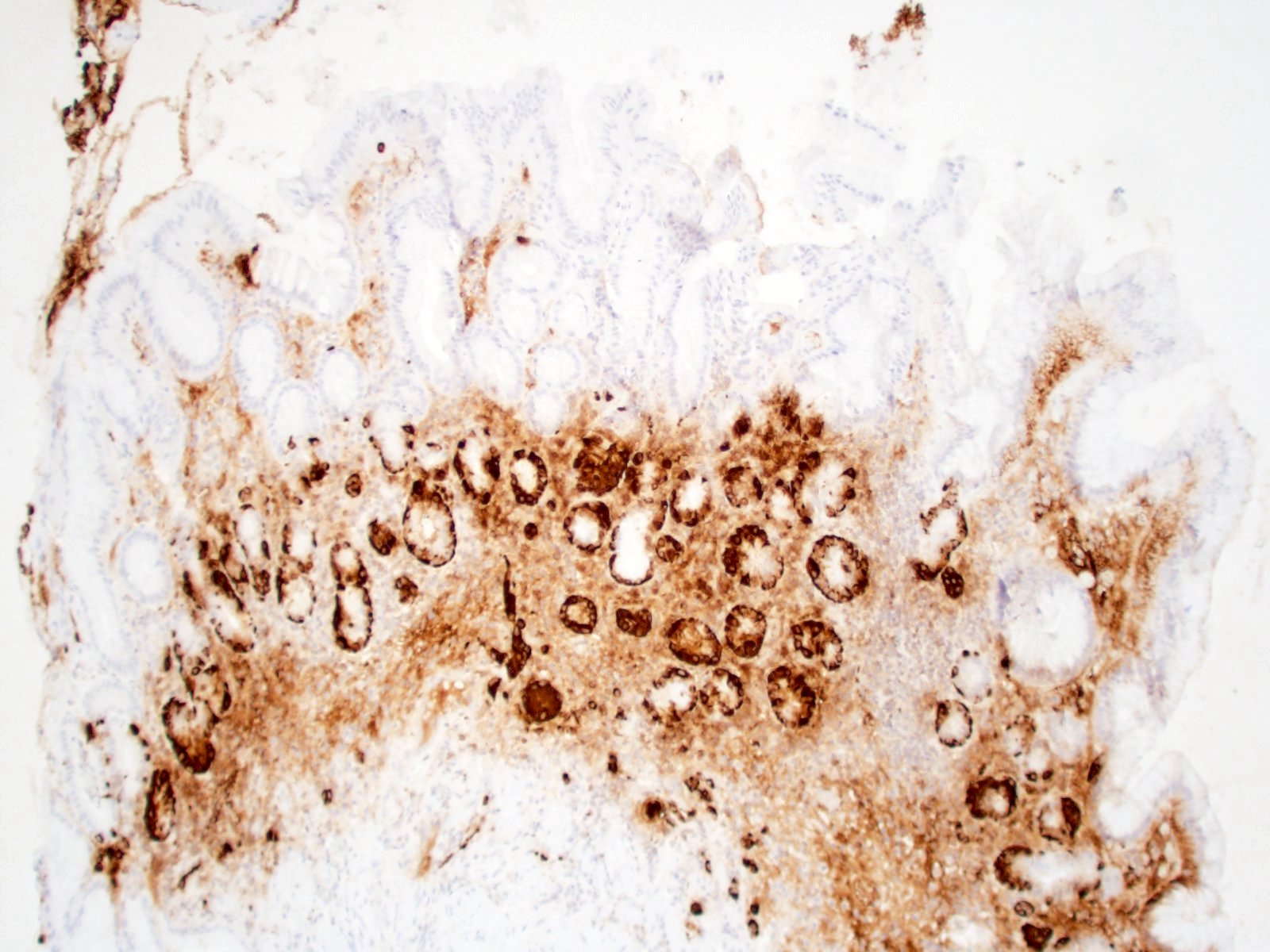

Positive stains

- Intestinal metaplasia can be highlighted by mucin 2 (MUC2) and Alcian blue, pH 2.5 (Cancer Res 1999;59:1003, Acta Biomed 2018;89:93)

- Pseudopyloric metaplasia can be highlighted by mucin 6 (MUC6) and trefoil factor 2 (TFF2) (J Pathol 2018;245:132)

- Enterochromaffin-like cell (ECL) hyperplasia can be highlighted by synaptophysin and chromogranin A (Pathologica 2021;113:5)

Negative stains

- Negative gastrin IHC in antralized (loss of oxyntic glands) gastric body (no G cells present confirms biopsy is from body or fundus)

- Negative H. pylori IHC excludes atrophic H. pylori gastritis and increases the likelihood of autoimmune atrophic gastritis (Arch Pathol Lab Med 2019;143:1327)

Videos

Histology of atrophic gastritis

Histology of autoimmune atrophic gastritis

Sample pathology report

- Gastric polyps, biopsies:

- Chronic atrophic gastritis, enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell hyperplasia and intestinal metaplasia (see comment)

- Helicobacter pylori immunostain is negative

- Comment: Sample of gastric body type mucosa is confirmed by gastrin negative immunostaining. Synaptophysin and chromogranin A highlight linear and micronodular ECL hyperplasia. Combined morphologic and immunohistochemical findings suggest atrophic gastritis, autoimmune type and confirmatory testing (such as antiparietal or anti-intrinsic factor serologies and serum gastrin and B12 levels) may be considered.

- No evidence of dysplasia or infiltrative process identified in the submitted specimen.

Differential diagnosis

- Nonatrophic H. pylori gastritis:

- Antral predominant acute or chronic inflammation with a top heavy, band-like distribution

- Loss of glands not prominent

- Lymphocytic gastritis:

- > 20 - 25 intraepithelial lymphocytes/100 epithelial cells

- Loss of glands not prominent

- Collagenous gastritis:

- Thickened subepithelial collagen band (> 10 μm) with entrapment of capillaries

- Loss of glands not prominent

- Reactive gastropathy:

- Foveolar hyperplasia, smooth muscle hyperplasia and minimal inflammation

- Loss of glands not prominent

- Reference: Virchows Arch 2018;473:533

Additional references

Board review style question #1

A 60 year old man with abdominal pain undergoes an upper endoscopy and biopsies from the body of the stomach are shown. What cell type is lost that leads to a decrease in acid production and what micronutrient is most commonly deficient as a direct result of this in these patients?

- Chief cells; calcium

- Chief cells; iron

- G cells; calcium

- Parietal cells; calcium

- Parietal cells; iron

Board review style answer #1

E. Parietal cells; iron. Parietal cells in the stomach not only secrete intrinsic factor, which is important for the absorption of vitamin B12, but also produce hydrochloric acid, which is necessary for the conversion of ferric (Fe3+) iron to absorbable ferrous (Fe2+) iron. Iron deficiency is a common early finding in atrophic gastritis. Answers A, C and D are incorrect because by comparison, calcium absorption requires vitamin D and is inhibited by high levels of phytic acids, sodium and caffeine. Celiac disease is associated with vitamin D deficiency and therefore calcium deficiency. Answer C is incorrect because G cells secrete gastrin into systemic circulation, which stimulates the proliferation of parietal cells and ECL cells and is not directly involved in micronutrient absorption. Answers A and B are incorrect because chief cells secrete digestive enzymes, such as pepsinogen and lipase, that break down macronutrients, such as proteins and lipid; they are not directly involved in the absorption of micronutrients.

Comment Here

Reference: Atrophic gastritis

Comment Here

Reference: Atrophic gastritis

Board review style question #2

A 55 year old woman presents with vague upper abdominal discomfort, bloating and occasional nausea. Upper endoscopy reveals a thinning of the gastric mucosa with areas of erythema and multiple patchy white plaques scattered throughout the mucosal surface. Multiple biopsies are taken. Which of the following histologic findings would be most consistent with a diagnosis of atrophic gastritis?

- Antral predominant acute or chronic inflammation in a top heavy, band-like distribution

- Gastric mucosa with dilated capillaries, intravascular fibrin thrombi and reactive foveolar changes

- Increased gastric intraepithelial lymphocytes and expansion of the lamina propria by lymphocytes and plasma cells

- Loss of parietal cells and replacement of gastric glands by intestinal type epithelium

- Tortuosity and hyperplasia of foveolar epithelium with loss of mucin

Board review style answer #2

D. Loss of parietal cells and replacement of gastric glands by intestinal type epithelium. These are the defining histologic features of atrophic gastritis.

Answer C is incorrect because it is the common presentation for lymphocytic colitis. Answer B is incorrect because it lists the typical histologic features for gastric antral vascular ectasia. Answer E is incorrect because it describes the typical histologic features of reactive gastropathy. Answer A is incorrect because it is the common presentation for a typical H. pylori gastritis.

Comment Here

Reference: Atrophic gastritis

Comment Here

Reference: Atrophic gastritis