Table of Contents

Definition / general | Epidemiology | Sites | Pathophysiology | Diagrams / tables | Clinical features | Life cycle | Diagnosis | Laboratory | Prognostic factors | Prevention | Case reports | Treatment | Microscopic (histologic) description | Microscopic (histologic) images | Differential diagnosis | Additional referencesCite this page: Fadel H. Schistosomiasis. PathologyOutlines.com website. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/parasitologyschisto.html. Accessed April 2nd, 2025.

Definition / general

- Schistosomiasis or bilharziasis is among the most important parasitic diseases worldwide, afflicting 200 - 300 million individuals

- Adult male and female blood flukes inhabit veins of the mesentery or bladder

- Most important species infecting humans are Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma japonicum, Schistosoma mekongi, Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma intercalatum; other species infect humans less frequently

Epidemiology

- Schistosomiasis is an important cause of disease in many parts of the world, most commonly in places with poor sanitation

- School age children who live in these areas are often most at risk because they tend to spend time swimming or bathing in water containing infectious cercariae

- Risk factors: living in or travel to endemic areas and exposure to contaminated freshwater

- S. mansoni - distributed throughout Africa:

- In freshwater in southern and sub-Saharan Africa, including great lakes, rivers and smaller bodies of water

- Also Nile River valley in Sudan and Egypt, South America (Brazil, Suriname, Venezuela), Caribbean (low risk, includes Dominican Republic, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Lucia)

- S. haematobium - distributed throughout Africa:

- In freshwater in southern and sub-Saharan Africa, including great lakes, rivers and smaller bodies of water

- Also Nile River valley in Egypt, Mahgreb region of North Africa

- Found in areas of the Middle East

- Eggs hatch within 15 - 30 minutes

- S. japonicum: Indonesia and parts of China and Southeast Asia

- S. mekongi: Cambodia and Laos

- S. intercalatum: parts of Central and West Africa

Sites

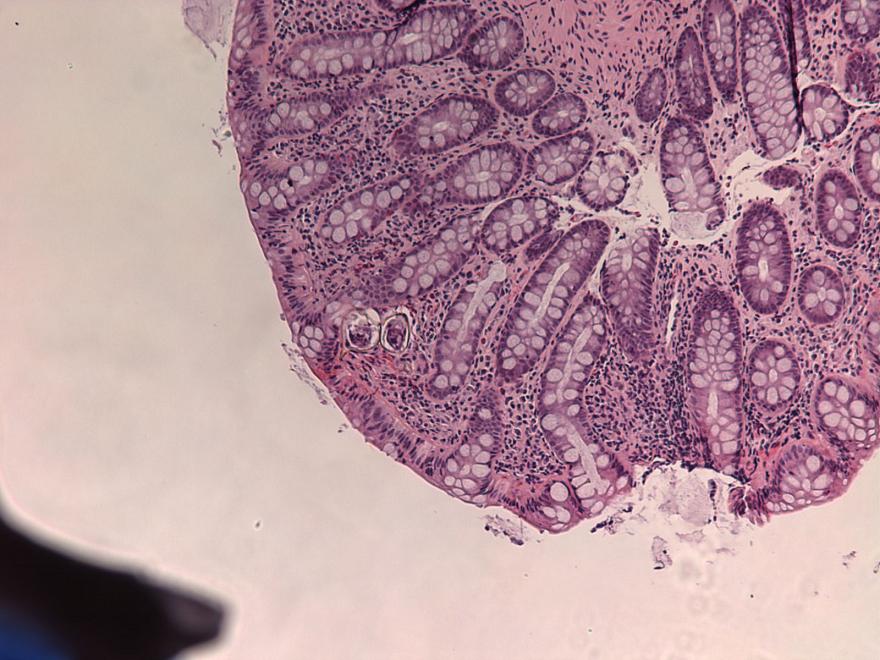

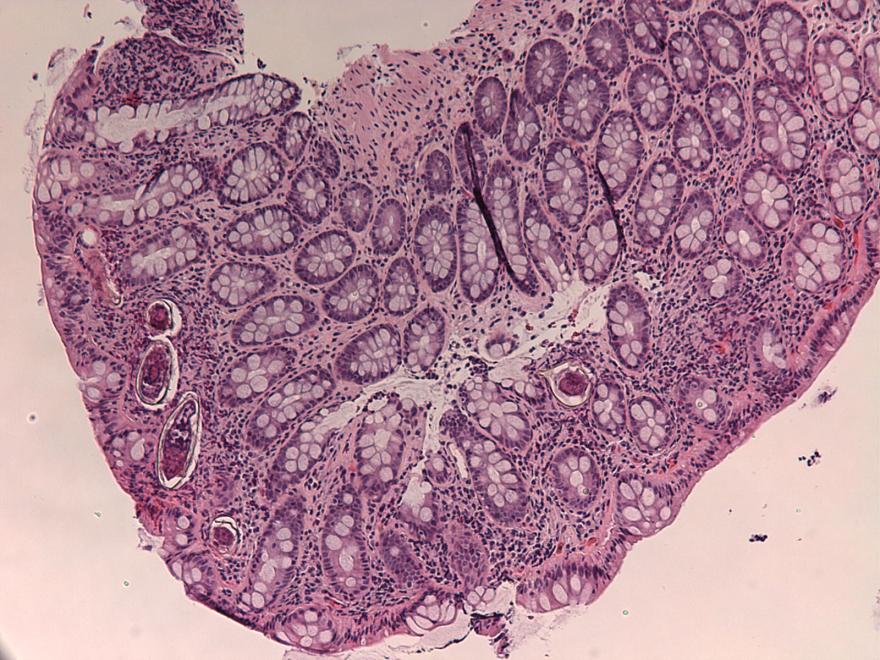

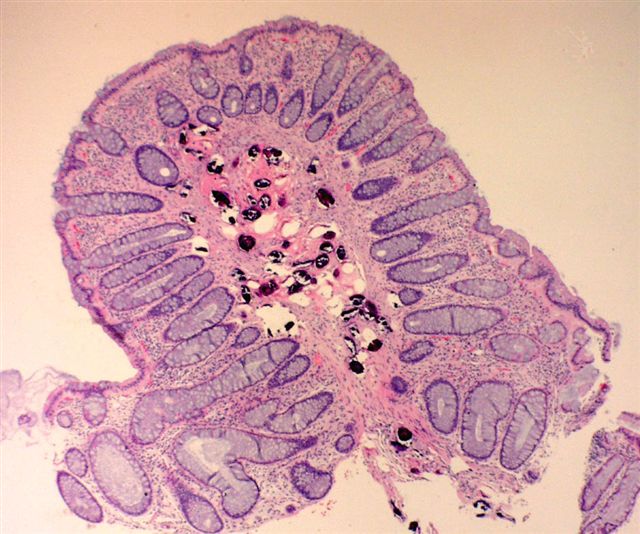

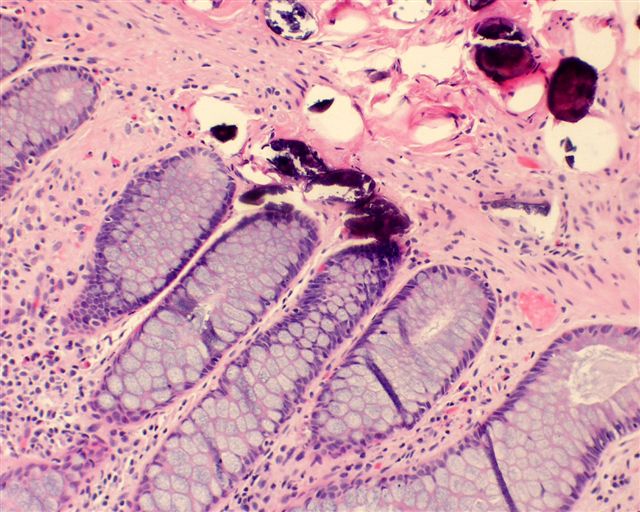

- Appendix

- Common, usually doesn't cause acute appendicitis

- May cause appendicitis in regions endemic for schistosomiasis

- Prominent eosinophilic infiltrate in appendix

Pathophysiology

- Eggs are deposited in smallest venule that can accommodate the female worm, where they elicit a strong granulomatous response that results in extrusion of the egg into the intestinal lumen or the bladder

- Pathology is primarily related to sites of egg deposition, number of eggs deposited and host reaction to egg antigens

Clinical features

- Symptoms of schistosomiasis result primarily from penetration of cercariae (cercarial dermatitis), from initiation of egg laying (acute schistosomiasis or Katayama fever) and as a late stage complication of tissue proliferation and repair (chronic schistosomiasis)

- Hours after cercarial penetration, a papular rash may develop, associated with pruritus

- This is a sensitization phenomenon resulting from prior exposure to cercarial antigens

- Most severe form of dermatitis occurs in individuals who are repeatedly exposed to cercariae of nonhuman (primarily avian) schistosomes

- Cercarial dermatitis or swimmer's itch occurs worldwide and is a well recognized entity in the United States (McPherson: Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods, 22nd Edition, 2011 [Chapter 62])

- Initiation of egg laying by mature worms 5 - 7 weeks after infection may result in acute schistosomiasis or Katayama fever, a serum sickness-like syndrome that occurs with heavy primary infection, especially that of S. japonicum

- Antigenic challenge to the host is thought to result in immune complex formation (McPherson: Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods, 22nd Edition, 2011 [Chapter 62])

- Chronic infection results in continued deposition of eggs, many of which remain in the body

- Granulomas produced around these eggs in the intestine and bladder are gradually replaced by collagen, resulting in fibrosis and scarring

- Eggs trapped in the liver may induce pipe stem fibrosis with obstruction to portal blood flow

- Occasionally, eggs are deposited in ectopic sites, such as the spinal cord, lungs or brain

- Coinfection with Schistosoma mansoni and HIV1 may occur (Parasit Vectors 2014;7:587)

Life cycle

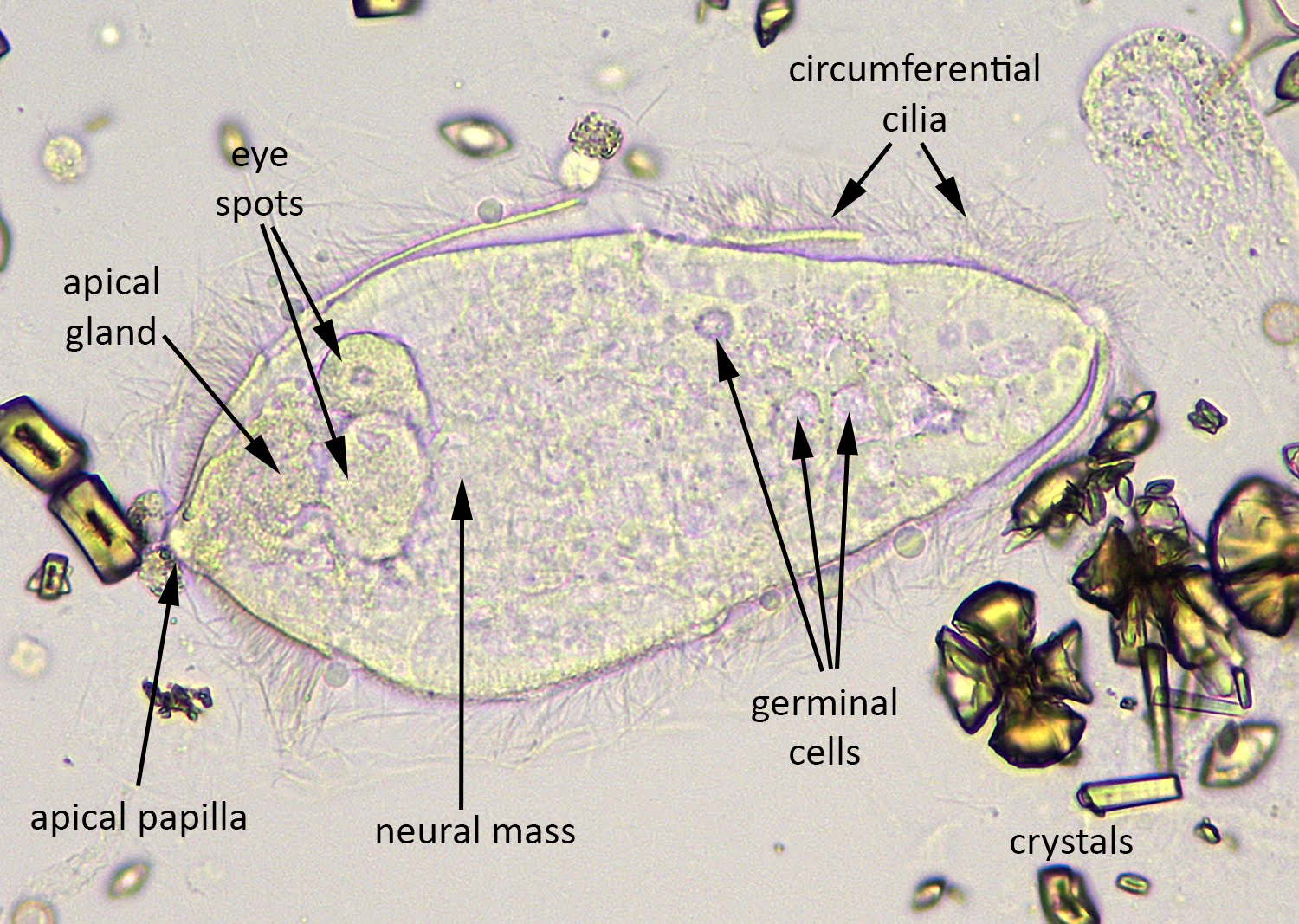

- Eggs are fully embryonated when passed and readily hatch when deposited in fresh water

- Miracidia penetrate an appropriate species of snail host, where they undergo transformation and extensive asexual multiplication

- After about 4 weeks, large numbers of fork tailed cercariae emerge from the mollusk

- Cercariae swim actively about for hours and readily penetrate the skin of susceptible hosts, including humans

- After penetration, the cercariae, now called schistosomules, enter the circulation and pass through the lungs before reaching the mesenteric portal vessels

Diagnosis

- Diagnosis is established by demonstrating eggs in feces or urine by direct wet mount or formalin ethyl acetate concentration methods

- Zinc sulfate concentration is not satisfactory for recovery of heavy schistosome eggs

- Eggs may be detected in biopsies of rectum, bladder or occasionally liver

- Egg hatching methods may occasionally be requested to determine viability or less commonly, to detect a limited infection

- Feces mixed in distilled water is placed in a flask, covered with foil (to keep out light), with neck or a sidearm exposed to bright light

- Miracidia, if present, actively swim to the light and can be detected using a hand lens

Laboratory

- Serologic tests may be useful for screening travelers to endemic areas, at risk patients with negative urine / stool examinations, monitoring response to therapy

- Although not widely available, a limited number of reference laboratories and the CDC provide testing

- CDC uses the Falcon assay screening test in a kinetic enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (FAST ELISA); sera that are positive by screening test are evaluated by immunoblot to improve specificity

- Results vary based on antigens used and the test methods employed

Prognostic factors

- Patients with coexisting HBV or HIV infections have worse prognoses

Prevention

- No vaccine is available

- Recommendations:

- Avoid swimming or wading in freshwater in endemic countries; ocean and chlorinated swimming pools are safe

- Drink safe water

- Apply vigorous towel drying after accidental, very brief water exposure to prevent penetration of skin by parasite; note: has limited effectiveness

Case reports

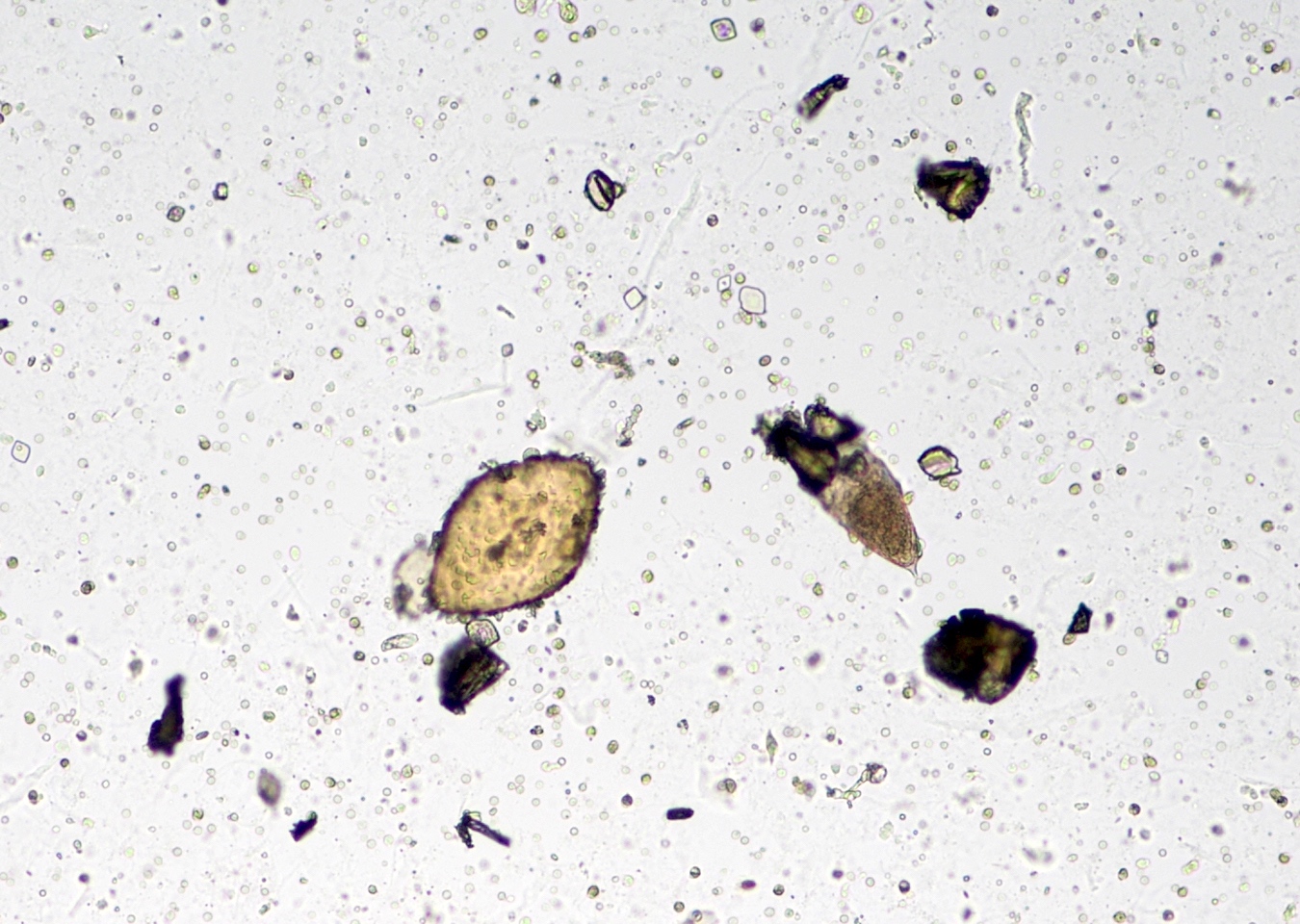

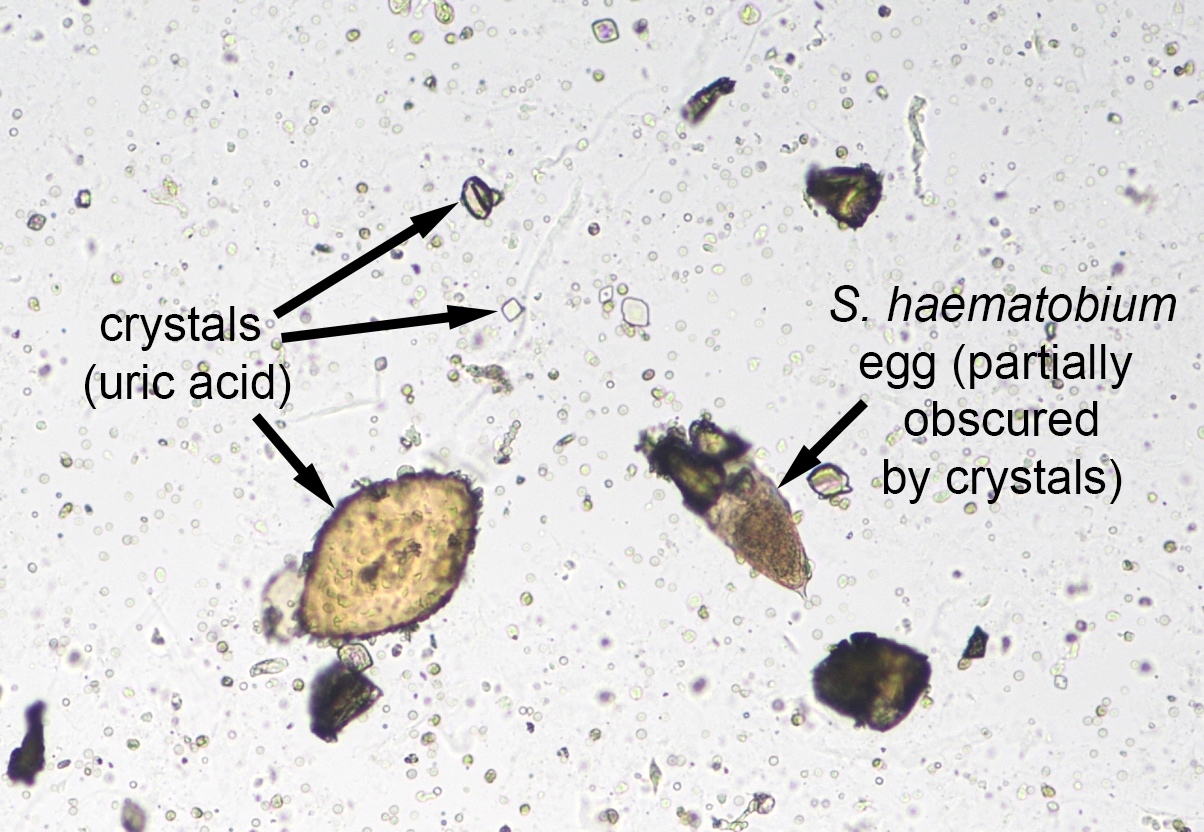

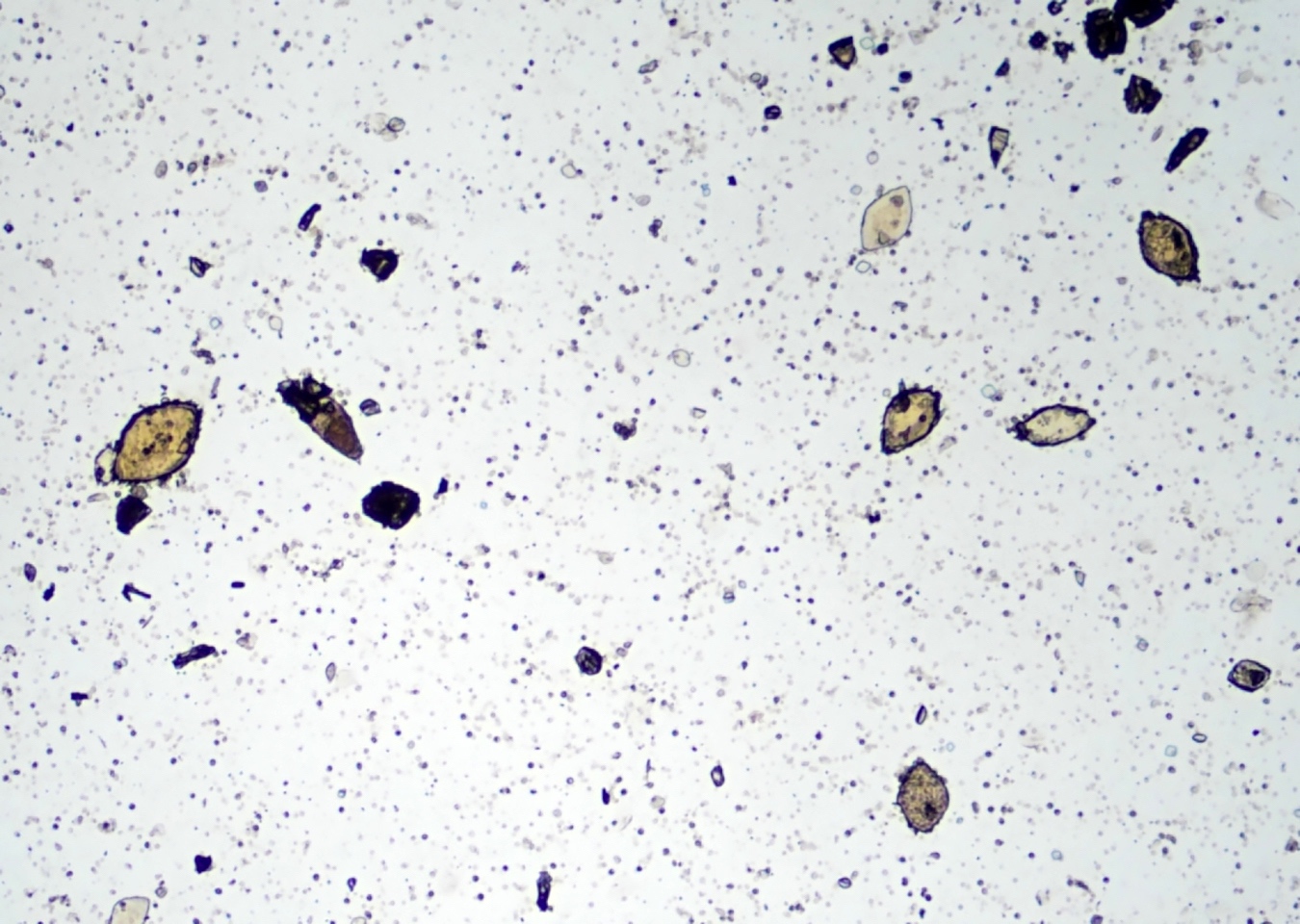

- Child from Sub-Saharan Africa with many ovoid, elongate, lemon-shaped objects seen in centrifuged urine specimen (Pritt: Creepy Dreadful Wonderful Parasites Blog - Case of the Week 511 [Accessed 26 October 2018])

- 20 year old woman with schistosomiasis manifesting as colon polyp (J Med Case Rep 2014;8:331)

- 31 year old woman with bowel endometriosis and schistosomiasis (Fertil Steril 2006;85:1060)

- Patient with unspecified object in urine sediment (Pritt: Creepy Dreadful Wonderful Parasites Blog - Case of the Week 518 [Accessed 13 February 2019])

- Three cases of appendicitis with Schistosoma haematobium eggs (APMIS 2006 Jan;114:72)

Treatment

- Praziquantel, taken for 1 - 2 days, is safe and effective for urinary and intestinal infections by all Schistosoma species

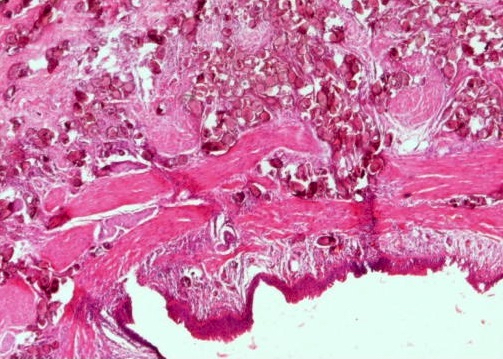

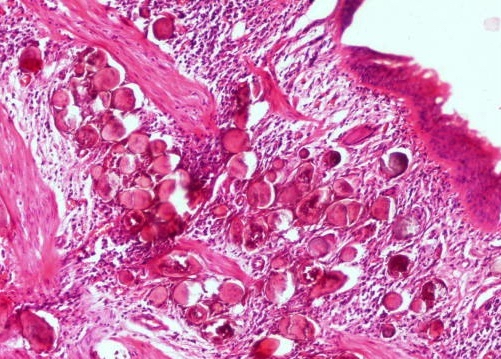

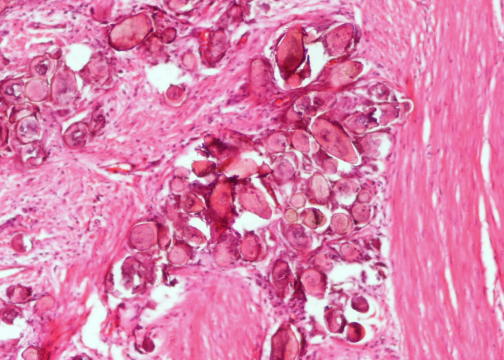

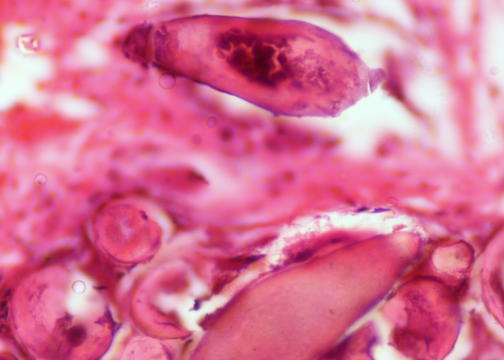

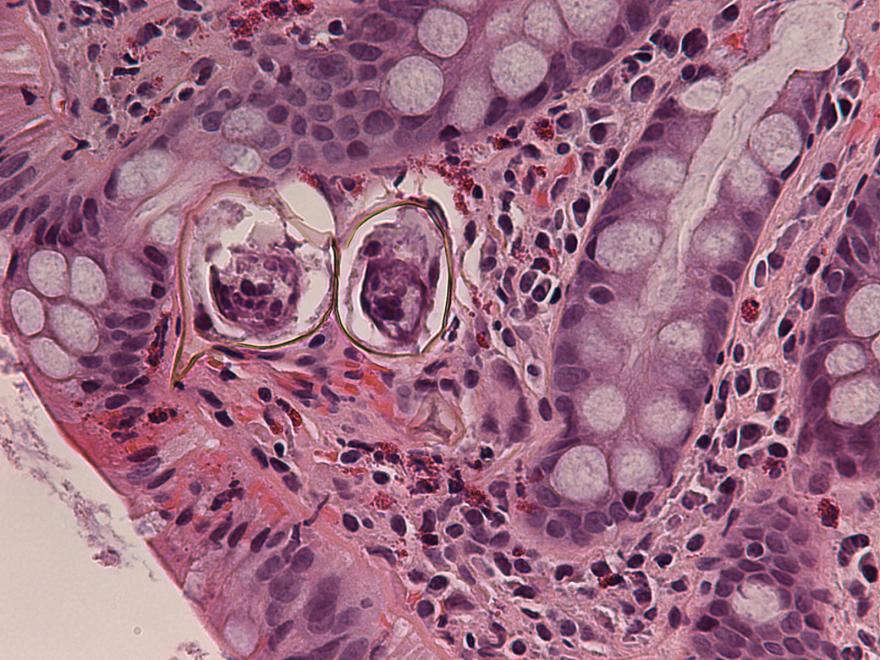

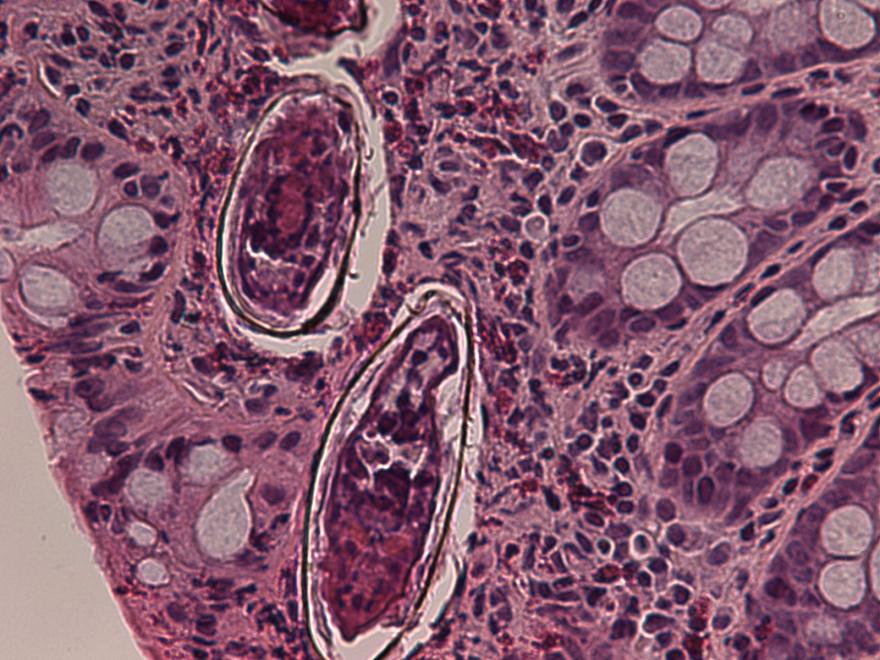

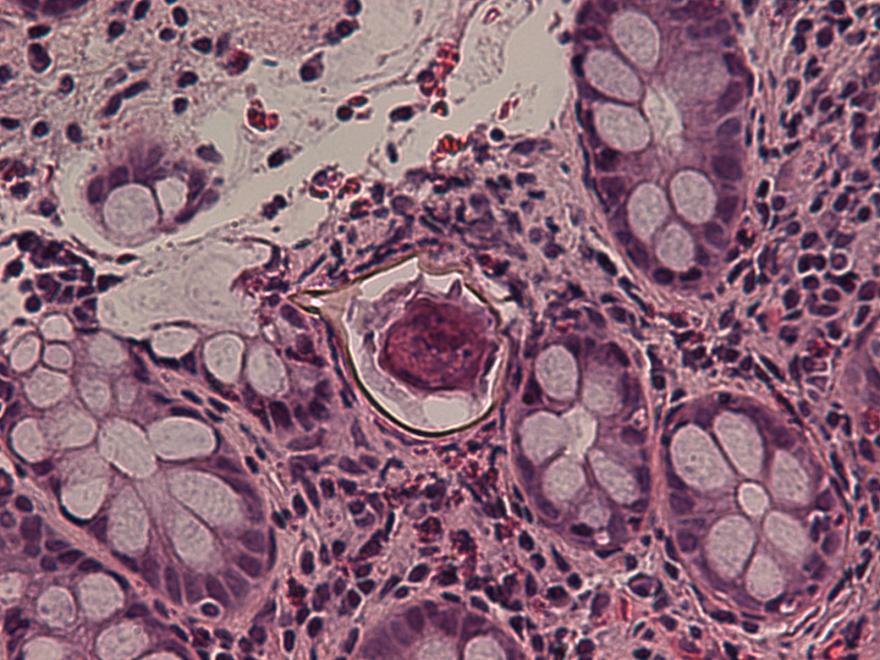

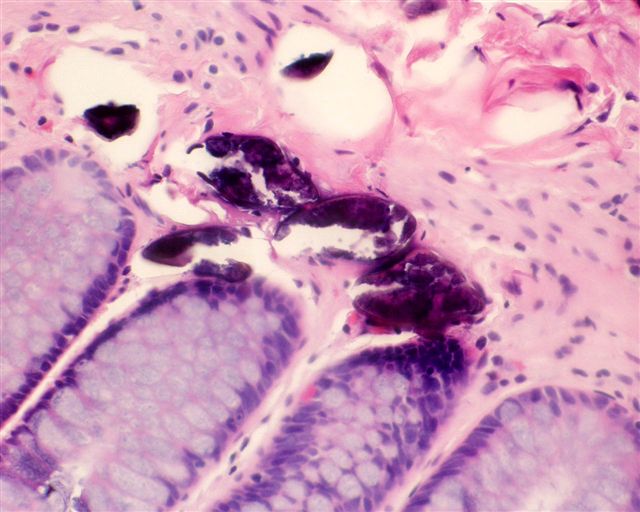

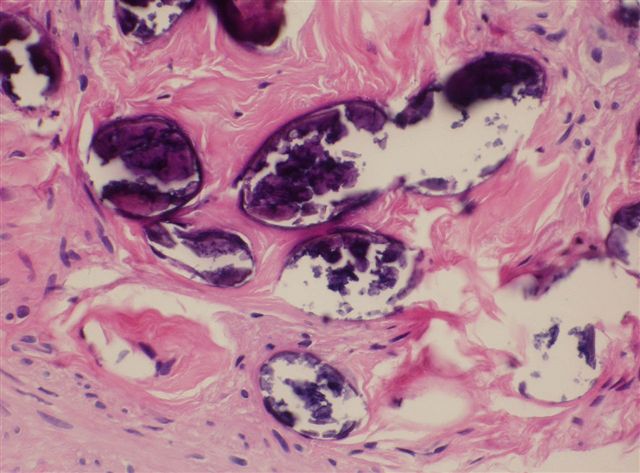

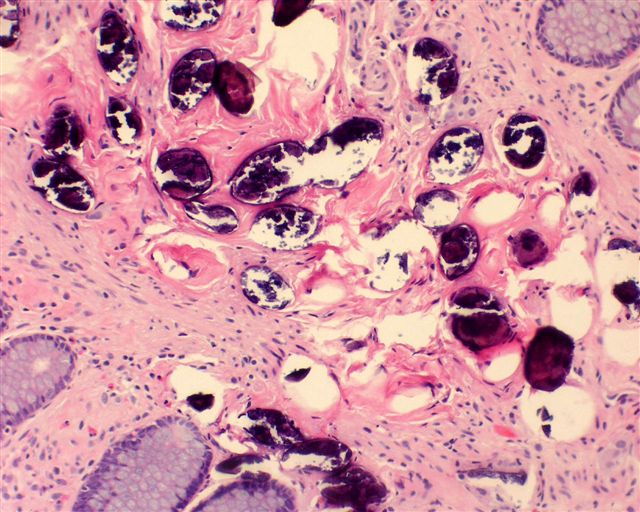

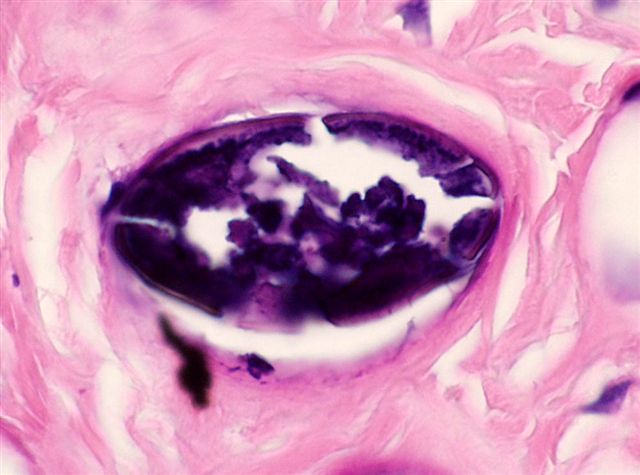

Microscopic (histologic) description

- Focal ulcers, eggs may be calcified, surrounded by fibrosis or granuloma

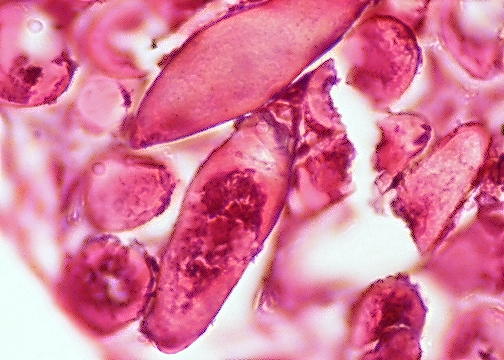

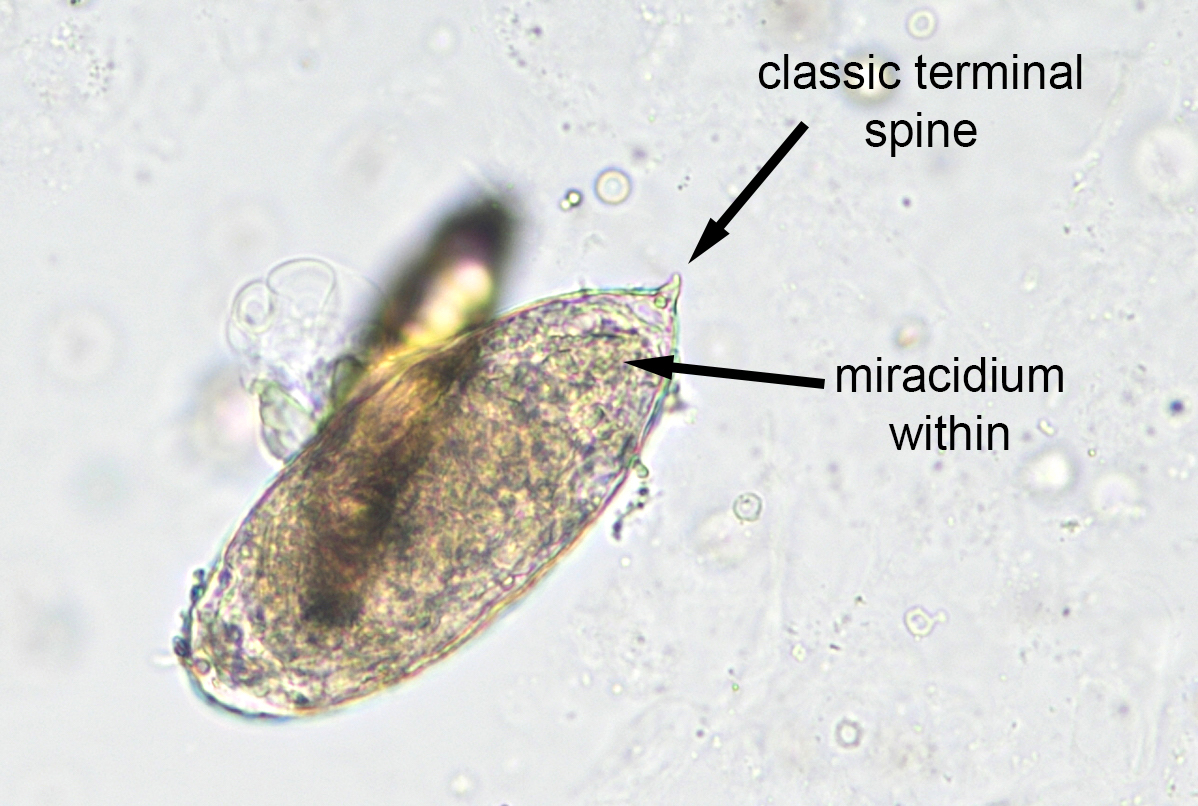

- S. haematobium: eggs are 110 - 170 by 40 - 70 microns, oval with terminal spine

- S. japonicum: eggs are 70 - 100 by 55 - 65 microns, oval / round (more rounded than other types), minute subterminal or no spine

- S. mansoni: eggs are 110 - 175 by 45 - 70 microns with thin transparent shell and definite lateral spine

- Adult female schistosomes are slender, measuring up to 26 mm by 0.5 mm

- Males, which are slightly shorter, enfold a female using the lateral margins of the body (the gynecophoral canal) to assist in sperm transfer

- When examined in situ, schistosomes are often found in copula

Microscopic (histologic) images

Scroll to see all images:

Contributed by Kiran Alam, M.B.B.S., M.D., Anshu Jain, M.B.B.S., M.D., Veena Maheshwari, M.B.B.S., M.D., Farhan A. Siddiqui, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Ershad ul Haq, M.B.B.S., M.D.

Contributed by Jennifer Stumph, M.D.

Contributed by Lisa Cerilli, M.D.

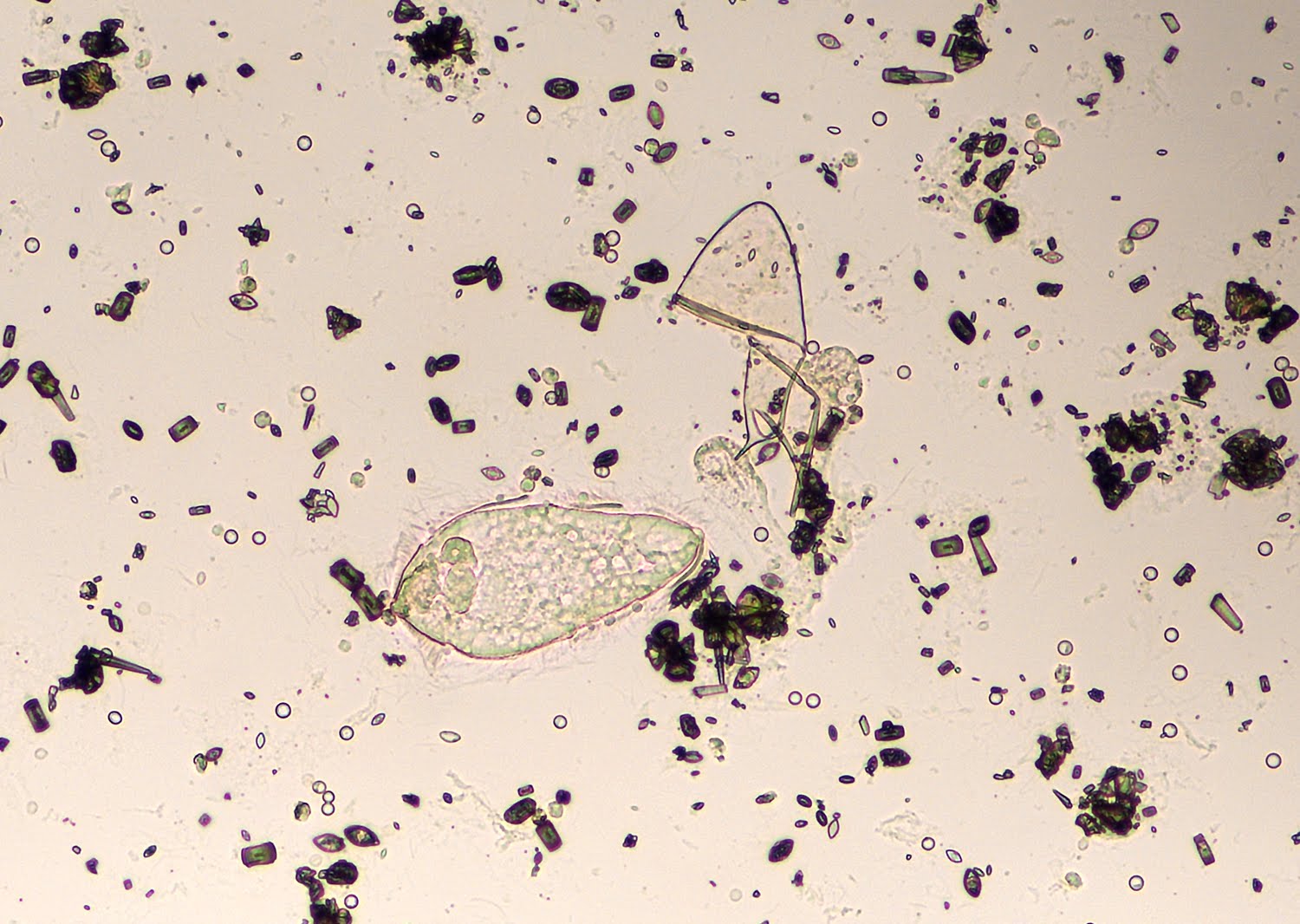

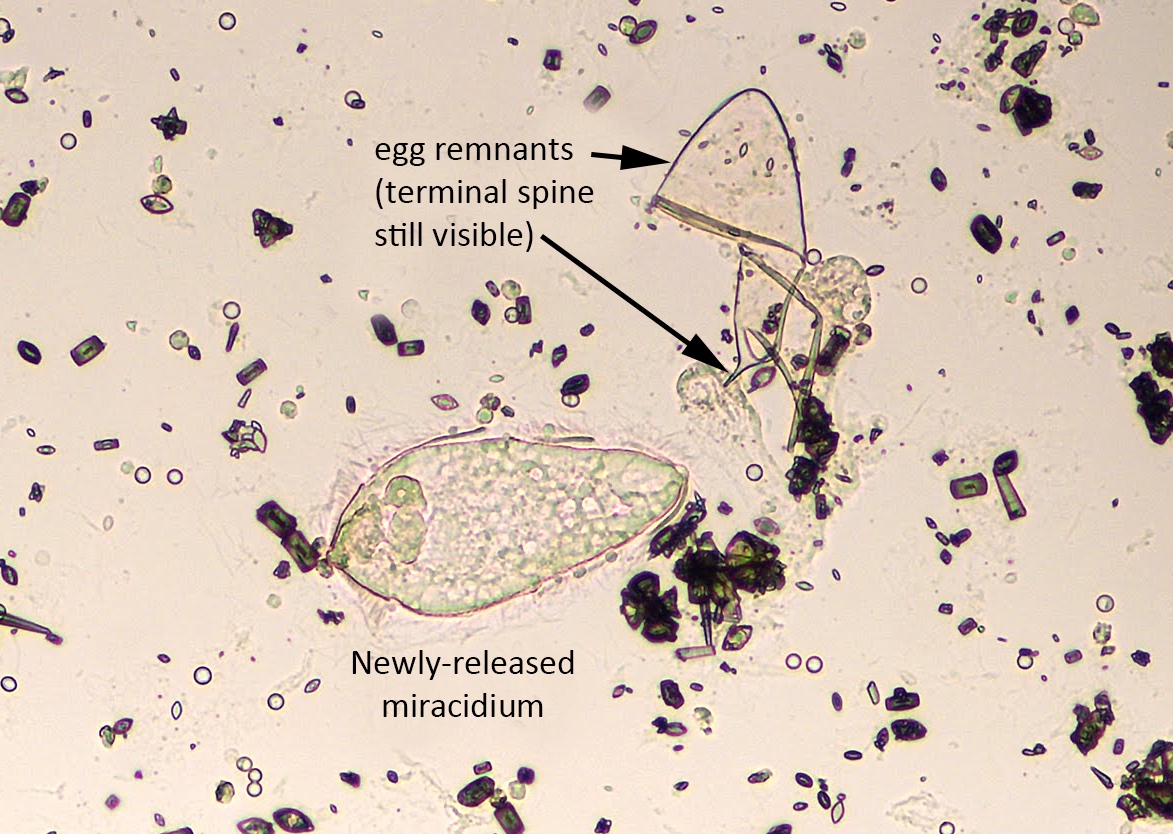

Contributed by Bobbi Pritt, M.D. and Heather Rose

Contributed by Bobbi Pritt, M.D. and Sarah Jung, M.D.

Images hosted on other servers:

Schistosoma haematobium - oval eggs with terminal spine:

Differential diagnosis

- Uric acid crystals: have size variability and points on both ends, like a lemon; in contrast, S. haematobium eggs have a defined "pinched off" terminal spine and larval form (miradium) within (Pritt: Creepy Dreadful Wonderful Parasites Blog - Answer to Case 511 [Accessed 26 October 2018])

Additional references

- Parasite Immunol 2006;28:613, Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:411, Arch Pathol Lab Med 2005;129:544, CDC: Parasites [Accessed 10 January 2018], eMedicine: Schistosomiasis (Bilharzia) [Accessed 10 January 2018], eMedicine: Emergent Management of Acute Schistosomiasis [Accessed 10 January 2018], Wikipedia: Schistosomiasis [Accessed 10 January 2018], Pritt: Creepy Dreadful Wonderful Parasites Blog - Answer to Case 518 [Accessed 13 February 2019]