Table of Contents

Definition / general | Essential features | ICD coding | Epidemiology | Sites | Pathophysiology | Etiology | Clinical features | Diagnosis | Laboratory | Prognostic factors | Case reports | Treatment | Clinical images | Microscopic (histologic) description | Microscopic (histologic) images | Peripheral smear description | Peripheral smear images | Positive stains | Molecular / cytogenetics description | Differential diagnosis | Additional references | Board review style question #1 | Board review style answer #1 | Board review style question #2 | Board review style answer #2 | Board review style question #3 | Board review style answer #3Cite this page: Lieberman JA. Leishmania. PathologyOutlines.com website. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/parasitologyleishmania.html. Accessed April 1st, 2025.

Definition / general

- Vector borne intracellular protozoan parasite

- Class: Kinetoplastida

- Order: Trypanosomatida

- Morphology (human stage, amastigote forms)

- Size: 1 - 3 x 3 - 6 microns, ovoid

- Kinetoplastid: looks like a small second nucleus and is a helpful feature for identification

- Composed of intercalating rings of DNA, serves key metabolic functions and possible drug target

- Flagellum: not produced by amastigote forms

Essential features

- Vector borne disease, transmitted by a sandfly bite

- Latin America, Middle East, Asia Minor, parts of Africa and Mediterranean

- 3 forms: cutaneous, mucocutaneous (may be disseminated) and visceral

- Cutaneous has a prototypical ring shaped ulcer; may regress spontaneously, although recurrence possible

- Mucosal and disseminated can be severely disfiguring

- Visceral presents with hepatosplenomegaly and hematopoietic suppression; usually fatal if untreated

- Amastigotes are detectable within macrophages / monocytes

- Kinetoplastid (like a second, small nucleus) is a helpful morphologic feature

- Culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are diagnostic; available at select reference laboratories in the U.S. (e.g., CDC)

- Consult reference laboratories prior to specimen collection

ICD coding

Epidemiology

- Parasite transmitted by sandfly bite (genera: Phlebotomus, Lutzomyia)

- Dogs are likely an important reservoir in and around human settlements (Vet Parasitol 2007;149:139)

- Global distribution (Acta Trop 2017;176:150):

- Africa, Asia / Middle East, Americas, Mediterranean

- Within the Americas, Latin America and particularly Bolivia have high prevalence

- 350 million people at risk (F1000Res 2017;6:750, Acta Trop 2017;176:150, Acta Trop 2018;177:135)

- 1.5 - 2 million cases/year

- 70,000 deaths/year

Sites

- Cutaneous (most common form of disease):

- Localized

- Diffuse

- Mucocutaneous:

- Especially nasopharynx, pharynx, perioral skin

- Brazil, Bolivia and Peru account for 90% of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis cases

- Visceral (kala azar, black fever):

- Reticuloendothelial system, marrow

- Usually fatal if untreated

- Reference: F1000Res 2017;6:750

Pathophysiology

- Transmission:

- Promastigote injected with infected sandfly saliva and phagocytosed by monocytes / macrophages

- Amastigotes develop from promastigotes, replicate inside monocytic phagocytes

- Circulating monocytes with amastigotes ingested by naive sandfly

- Proinflammatory immune response is critical for control of parasite replication (J Immunol 2016;196:4100, Ann Hum Genet 2017;81:41, J Immunol 2010;185:6205)

- Critical role for Th1 T cells and M1 macrophages

- Compromised T cell immunity or T cell anergy and Th2 biasing contribute to kala azar, disseminated disease

- Genetic risk factors include polymorphisms in cytokine receptors, IgG receptors

Etiology

- Many species can cause disease (F1000Res 2017;6:750, Acta Trop 2017;176:150, Acta Trop 2018;177:135, Parasite Immunol 2009;31:254)

- Cutaneous (localized and diffuse):

- L. major (Old World / Middle East)

- L. tropica, L. mexicana, L. panamensis (Americas)

- L. guyanensis often causes multiple cutaneous lesions

- Mucocutaneous (members of Viannia subgenus):

- L. braziliensis, part of Viannia subgenus

- Forms a species complex that includes L. peruviana; may not be distinguishable by laboratory testing

- L. peruviana is not thought to cause mucocutaneous disease

- L. guyanensis, L. panamensis, part of Viannia subgenus

- Form a species complex; may not be distinguishable by laboratory testing

- L. braziliensis, part of Viannia subgenus

- Visceral / kala azar:

- L. infantum (Mediterranean), L. donovani (India and East Africa)

- L. chagasi, L. amazonensis, L. tropica (Americas)

Clinical features

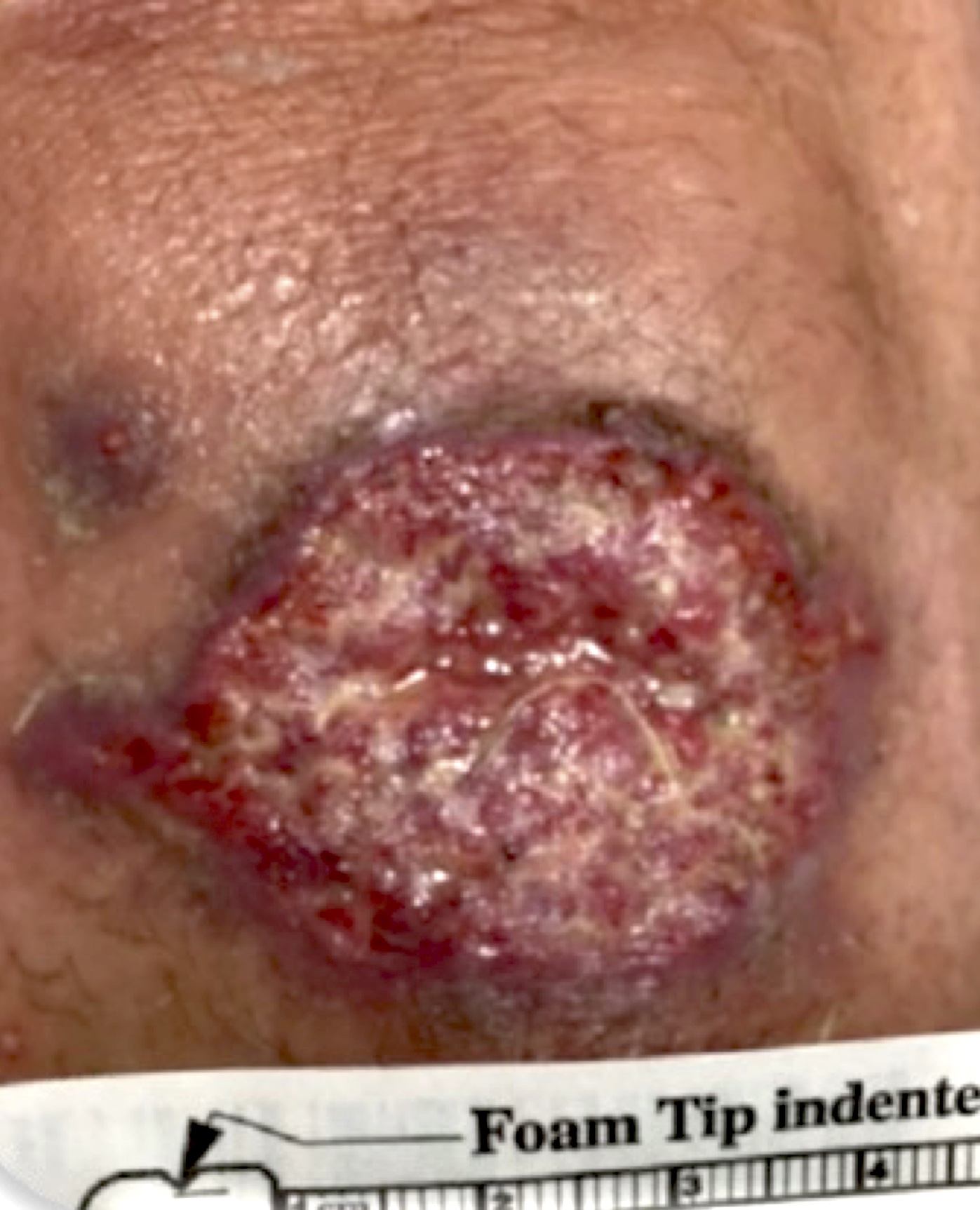

- Cutaneous:

- Small, erythematous, often pruritic papule

- Evolves into round, ring shaped, raised edges, eroded / ulcerated coin lesions; crust may form

- May last from months to years

- Afebrile disease with local lymphadenopathy

- May progress to scarring and local deformity

- ~33% of patients relapse

- Mucocutaneous:

- Ulcerative lesions of mucosal surfaces or (perioral) skin

- May be destructive of soft tissue, cartilage

- Symptoms range from mild pain to significant odynophagia

- Part of the spectrum of disease from cutaneous to disseminated

- Occurs in 1 - 10% of patients with localized leishmaniasis in endemic regions, especially South America

- Disseminated (F1000Res 2017;6:750, Acta Trop 2017;176:150, Acta Trop 2018;177:135):

- Multiple lesions on multiple body sites

- Often involves mucosal surfaces

- Visceral leishmaniasis / kala azar (F1000Res 2017;6:750, Parasite Immunol 2009;31:254):

- Febrile disease (irregular), night sweats, cachexia

- Hepatosplenomegaly is often apparent

- Multi / trilineage hematopoietic disruption may be apparent, often significant anemia

- Hemophagocytosis variable

- No cutaneous lesions

- Likely lethal if untreated

- Deaths occur due to hemorrhage, multiorgan system failure, superinfection

- Recurrence possible in immunocompromised (e.g., HIV)

Diagnosis

- Multiple diagnostic tests may be required (Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017;96:24)

- Generally performed at reference laboratory

- Contact reference laboratory before specimen collection

- Species level identification is recommended

- Tissue smears and full thickness skin biopsy for histopathology (amastigotes visualization)

- Microbiologic culture (to identify nonleishmanial causes of disease); parasite culture is rarely performed except at select reference laboratories

- E.g., McGill University / Canadian National Reference Centre for Parasitology (non-CLIA laboratory) (McGill: National Reference Centre for Parasitology [Accessed 27 July 2022])

- DNA based molecular (PCR) testing, most sensitive:

- Ability to distinguish species, especially Viannia subgenus, is a key component of Leishmania molecular testing

- University of Washington (UW Medicine) Molecular Microbiology Laboratory (University of Washington: Leishmania DNA Detection by PCR [Accessed 27 July 2022])

- Montenegro (leishmanin) skin test is not available in North America

- Equivalent to purified protein derivative (PPD) for M. tuberculosis

Laboratory

- Culture

- Thin smear / touch prep:

- Thin smear to detect parasite and determine parasitemia in cases of visceral leishmaniasis

- Touch prep for identification of intracellular (monocytes) parasites of cutaneous / mucocutaneous lesions

- Giemsa stain recommended

- Histopathology:

- Lymphohistioplasmacytic infiltrate

- Epithelioid granulomata

- Leishmania amastigotes within histiocytes

- Molecular:

- CDC testing back online as of July 2022; see CDC - DPDx

- Rare clinical reference laboratories offer testing

- Specimen collection criteria are very important; please review specimen collection guidelines with reference laboratory before specimen collection

- Organism specific assays are the most sensitive, capable of detecting single genome per reaction (University of Washington: Leishmania DNA Detection by PCR [Accessed 27 July 2022])

- May also be detected by 28S / ITS PCR on the basis of eukaryotic homology (i.e., to fungal organisms), although assay performance not known, not specifically validated (Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:2035)

- 28S does not permit species specific identification

Prognostic factors

- Associated with increased risk of mucosal leishmaniasis (Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017;96:24)

- Positive prognostic factors:

- Immunocompetence

- Small lesion size (< 1 cm)

- Resolution of lesions without therapy

- Lack of mucosal involvement

- Negative prognostic factors:

- Concomitant HIV, other causes of T cell impairment

- > 4 lesions, each > 1 cm

- Single lesion ≥ 5 cm

- Prior treatment failure

- Diffuse or disseminated disease

- Significant regional lymphadenopathy

Case reports

- 27 month old boy with cutaneous leishmaniasis in North Dakota (Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:e73)

- 16 year old American girl returning from Israel with cutaneous leishmaniasis (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2018;7:e178)

- 32 year old woman with lupus, macrophage activation syndrome and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (Acta Med Port 2018;31:593)

- 42 year old woman with nasal perforation nearly 30 years after exposure (Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018;99:327)

- 200 U.S. soldiers deployed in Iraq with asymptomatic visceral Leishmania infantum infection (Clin Infect Dis 2019;68:2036)

Treatment

- Patients infected with Leishmania spp. from subgenus Viannia (L. [Viannia] spp.) are at increased risk of mucosal disease and treatment is indicated; guidelines are not unanimous, however, for immunocompetent persons with uncomplicated, low risk skin lesions caused by species outside subgenus Viannia (Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017;96:24, Acta Trop 2017;176:150)

- Some authors argue against treatment if there is spontaneous resolution (Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017;96:24)

- Some authors recommend treating any patient with New World cutaneous leishmaniasis (Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017;96:24)

- Amphotericin B; liposomal formulation recommended for visceral leishmaniasis

- Pentavalent antimonial compounds (SbV); many are not available in the U.S. without special approval or drug trial

- Pentamidine

- Miltefosine (FDA approved oral drug)

- Azole antifungals (ketoconazole) may be an option

- Start antiretroviral therapy for untreated HIV+ individuals as soon as possible; monitor for relapse

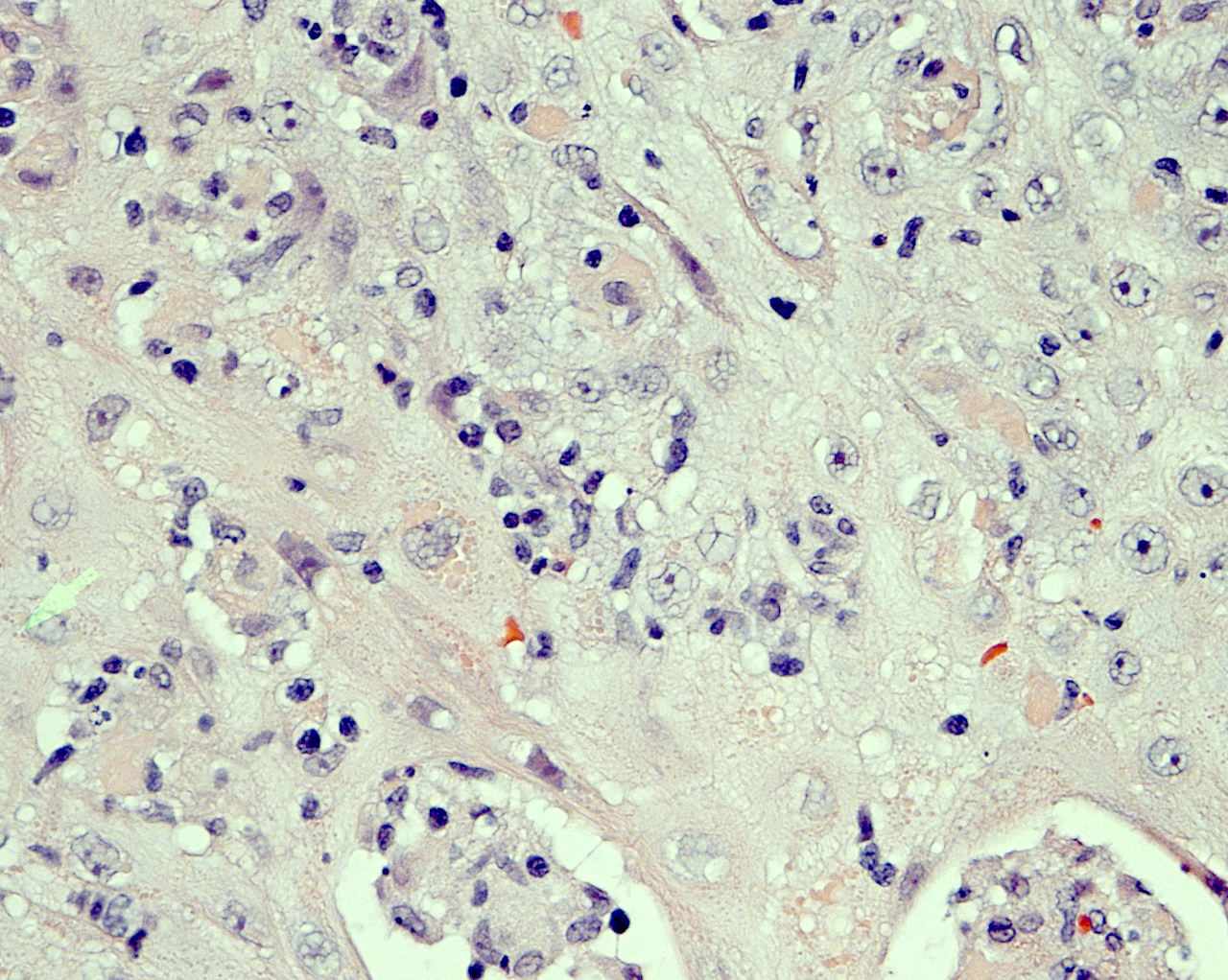

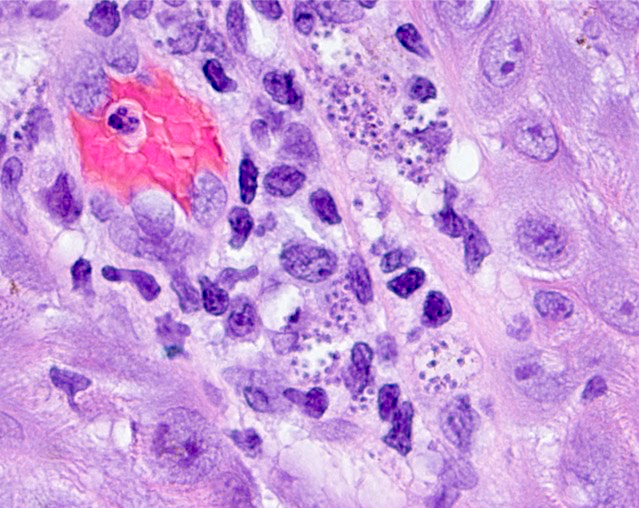

Microscopic (histologic) description

- Amastigotes are intracellular forms within monocytes / histiocytes

- Kinetoplast may be visible

- Histopathology:

- Histiocyte rich inflammation, often neutrophils and lymphocytes

- Necrosis may be present but negative for necrotizing granulomas

- Fibrosis often present

- Russell bodies may be present (nonspecific)

- References: J Cutan Pathol 2017;44:1005, Biomed Res Int 2020;2020:4926819

Microscopic (histologic) images

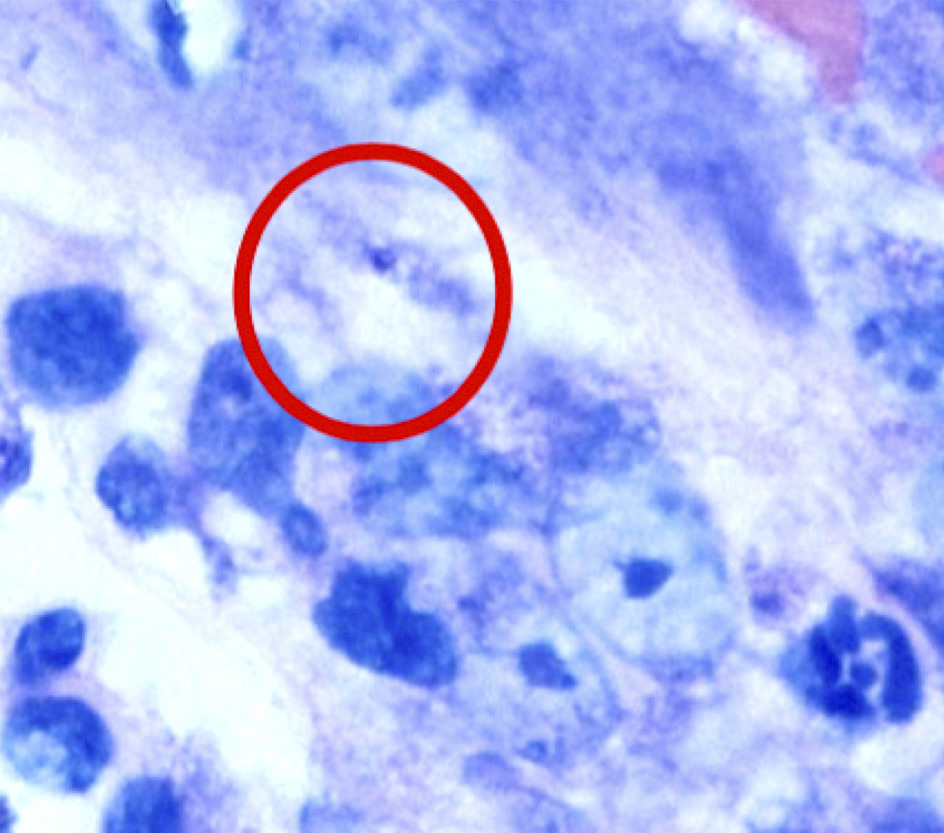

Peripheral smear description

- Monocytes contain intracellular organisms (amastigotes)

- Each amastigote contains a prominent nucleolus and a rod shaped kinetoplast

Peripheral smear images

Positive stains

- Giemsa

- Diff-Quik

- CD1a can stain amastigotes but has a low sensitivity (~50%) (J Cutan Pathol 2017;44:1005)

Molecular / cytogenetics description

- PCR is an important diagnostic tool for diagnosing leishmaniasis

- Primarily available at reference laboratories, including CDC, UW Medicine and Walter Reed (for U.S. servicemembers and beneficiaries, as well as Department of Defense employees)

- Consult prior to specific specimen collection is recommended (CDC: Practical Guide for Specimen Collection and Reference Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis [Accessed 27 July 2022])

- The parasite may be incidentally detected by 28S / ITS broad range fungal PCR (see above)

Differential diagnosis

- Mycobacterium leprae (leprosy / Hansen disease):

- Skin lesions in leprosy demonstrate altered pigmentation often with anesthesia

- Biopsy typically demonstrates foam cells and granulomatous inflammation; may involve nerve

- Acid fast bacilli (AFB) are seen with Ziehl-Neelson or Fite stains in the multibacillary form of the disease but often not visualized in paucibacillary disease

- Diagnosis is by clinical correlation, skin or nerve biopsy with demonstration of AFB

- PCR for M. leprae is not widely available

- Mycobacterium ulcerans (Buruli ulcer):

- Skin lesions are nodular and may or may not ulcerate

- When ulcerated, undermining edges are common; often irregular edges

- AFB are often present in nonulcerated tissue or at wound edge

- M. ulcerans can be cultured with growth at 33 °C; slow growing Mycobacterium

- PCR can distinguish from other organisms

- Skin lesions are nodular and may or may not ulcerate

- Rhinoscleroma (Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis):

- Mucosal / nasal septal ulcerated lesion that may mimic mucosal leishmaniasis

- Biopsy demonstrates histiocytic inflammation but negative for AFB

- Culture or PCR (16S rDNA) demonstrates K. rhinoscleromatis

- Botryomycosis (bacterial pseudomycosis):

- Rare suppurative and granulomatous reaction to chronic bacterial infection, often Staphylococcus aureus (other organisms have been implicated)

- Lacks geographic associations of leishmaniasis

- Skin lesions may also be chronic but are irregular, nodular and may ulcerate; may contain so called sulfur granules

- Visceral form can involve lung or other organs, appear as mass lesion rather than the diffuse hepatosplenomegaly seen in visceral leishmaniasis

- Microscopy demonstrates rich neutrophilic infiltrate, often with granulomatous inflammation and aggregates of bacteria with Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon (asteroid bodies)

- Bacterial culture or bacterial PCR (16S rDNA) may demonstrate S. aureus, other bacteria

- Hematopoietic neoplasms:

- Aggressive NK / T lymphoma (midline granuloma) in the nasopharynx:

- Clinical lesion may be ulcerated, mucosal lesion similar to cutaneous / mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

- Mycosis fungoides / cutaneous DLBCL in the skin:

- Lesions vary over time but typically erythematous, nonulcerated; may form nodules

- Biopsy reveals atypical lymphoid infiltrate, often with frankly neoplastic cells

- Flow cytometry and immunohistochemical staining confirms diagnosis

- Aggressive NK / T lymphoma (midline granuloma) in the nasopharynx:

- Pyoderma gangrenosum:

- Skin lesions are painful ulcers with irregular borders; frequently on the legs but may occur at other sites

- Associations with Crohn's disease and other autoimmune conditions

- Biopsy findings are nonspecific and change over time; early lesions include suppurative folliculitis with significant neutrophils; leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be present

- Mycobacteria and amastigotes are absent; wound cultures may demonstrate chronic superficial infection

Additional references

Board review style question #1

A 40 year old immigrant from a rural community in Northeastern Brazil presents to the clinic with a mildly painful, slightly itchy ulcer on his left shin. The lesion first presented 2 months ago as an erythematous lesion and has evolved to a 0.9 cm diameter, symmetric ulcer, with raised edges and a slight crust. He is afebrile and vital signs are stable. Physical exam is negative for pedal edema and stasis dermatitis. He is treated for mild hypertension but no other medical problems. Laboratory evaluation reveals an Hgb A1c of 6.1%. What is the most likely cause of this patient's skin lesion?

- Chronic venous insufficiency

- Cutaneous leishmaniasis

- Diabetic ulcer

- Hansen disease

- Primary cutaneous large B cell lymphoma, leg type

Board review style answer #1

B. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. This is a classic description of a cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion and Northeastern Brazil is a location of high endemicity. Although leprosy (Hansen disease) also occurs in Northeastern Brazil, this is not a typical presentation. The patient's laboratory findings of an elevated Hgb A1c suggest he is at increased risk of diabetes mellitus type 2 but does not meet criteria for diagnosis and thus a diabetic ulcer is unlikely. The patient has mild hypertension but is treated and does not have evidence of stasis dermatitis, making venous insufficiency unlikely. In addition, the symmetric and focal nature of the lesions is not typical for venous stasis lesions. Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma, leg type is a disease typically seen in older women and the skin lesion is more likely a firm, subepidermal nodule.

Comment Here

Reference: Leishmania

Comment Here

Reference: Leishmania

Board review style question #2

A 28 year old female Peace Corps volunteer of French and Scandinavian descent returns from Bolivia with a chronic, nonperforating erosion of the nasal septum. She has no other medical problems and no systemic symptoms. What is the best diagnostic approach to identify the cause of this patient's nasopharyngeal lesion?

- Culture for acid fast bacilli

- Flow cytometry

- KOH stain and direct microscopic exam for fungi

- Tissue biopsy for histopathology

Board review style answer #2

D. Tissue biopsy for histopathology. The patient has returned from an area where Leishmania is endemic and where mucosal leishmaniasis is particularly common. The diagnostic approach of choice is evaluation of tissue. However, tissue should also be sampled for culture to rule out other infections (fungal, bacterial), including rhinoscleroma (Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis) and botryomycosis (S. aureus). Acid fast organism infections are less likely than Leishmania in this immunocompetent individual. Fungal stains may be negative, even when organisms are isolated by culture. Flow cytometry would be useful in the diagnosis of an NK / T nasal type lymphoma (midline granuloma) but these aggressive lesions are more commonly associated with men of East Asian descent.

Comment Here

Reference: Leishmania

Comment Here

Reference: Leishmania

Board review style question #3

A 21 year old male soldier returns from deployment in the Middle East with fever, weight loss, anemia and an enlarged spleen. Thin smear of his peripheral blood demonstrates monocytes with cytoplasmic inclusions. What is the most likely risk factor for his infection?

- Epstein-Barr virus infection

- Exposure to dogs

- Exposure to sandflies

- No specific risk factor for spontaneous hematopoietic neoplasm

Board review style answer #3

C. Exposure to sandflies. The patient recently deployed to a Leishmania endemic area and presents with possible visceral leishmaniasis. The most important risk factor is an exposure to sandflies. Leishmania spp. is a vector borne parasite transmitted to humans when promastigotes are injected and phagocytosed by monocytes. These morph into amastigotes, which can be seen on peripheral smears as round forms with a nucleus and often a smaller nucleus-like kinetoplast. Although dogs are likely an important reservoir for Leishmania spp. transmission, transmission requires the parasite cycle through the sandfly stages.

Comment Here

Reference: Leishmania

Comment Here

Reference: Leishmania