Premalignant disease is typically defined as a cluster of cells with some malignant properties but which do not have or have not demonstrated the ability to invade into deeper tissue or to spread to other parts of the body (Curtius 2017).

Premalignant disease is important because

- It is a risk factor for cancer; we must either remove it surgically, destroy it with other treatment or follow it carefully.

- It may indicate that invasive cancer is currently present and we have to look harder to find it.

- It helps us to better understand how cancer arises.

Almost all adult cancer has, and apparently arises from, a known premalignant disease:

- To our knowledge, the only exceptions are glioblastoma and Hodgkin lymphoma, although we have speculated that they may also be associated with premalignant disease based on patterns of molecular changes in cells (email me other cancer types without known premalignant disease at Nat@PathologyOutlines.com).

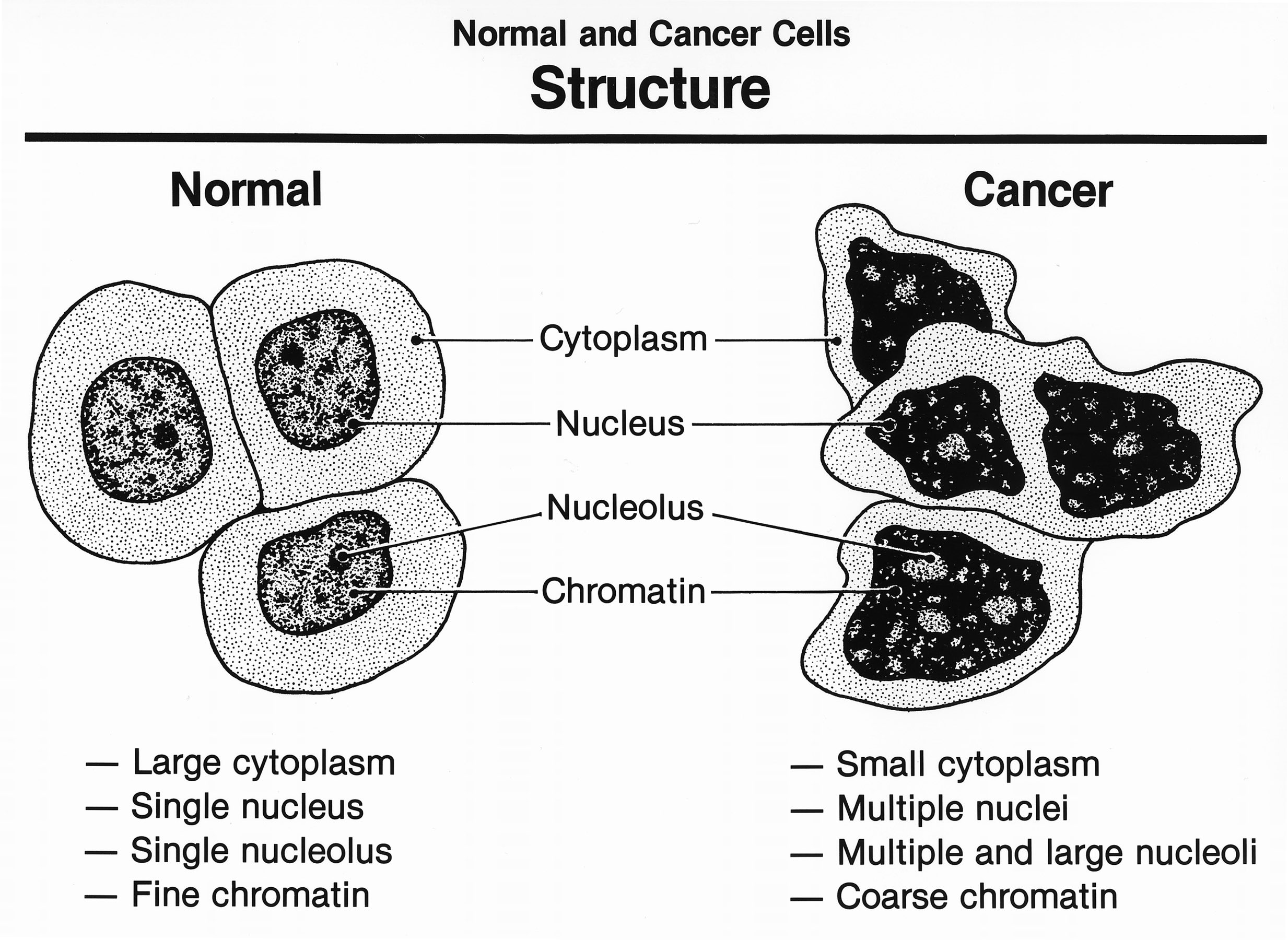

The following features of cancer are commonly seen under the microscope in premalignant disease and invasive cancer:

- Cell nuclei are larger and darker than normal because they contain more DNA which is associated with more frequent cell division.

- Cells are more varied than usual due to mutations and other background changes.

- The arrangement of cells is disorganized compared to usual.

- For invasive cancers, cells do not stay where they belong.

Source: Wikipedia

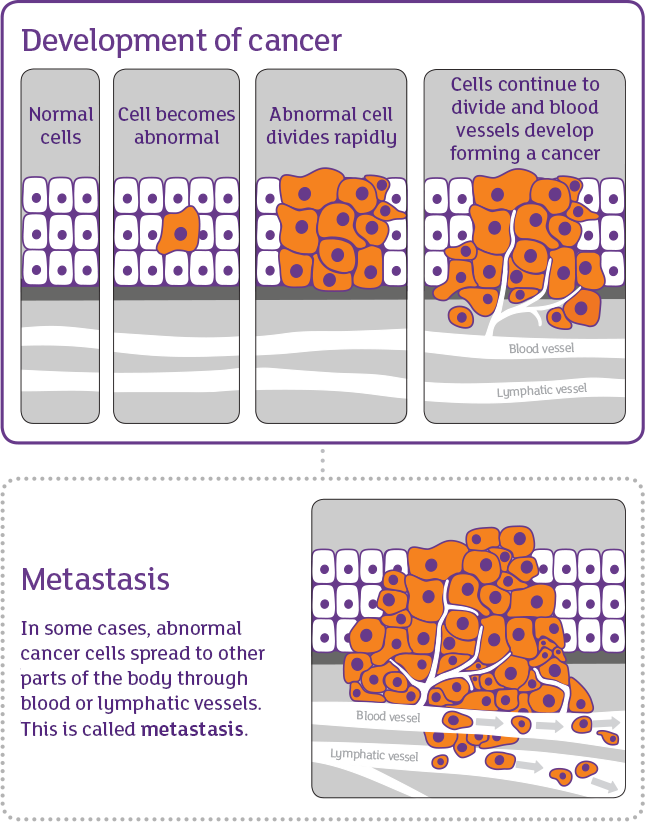

Source: Cancer Institute NSW (Australia)

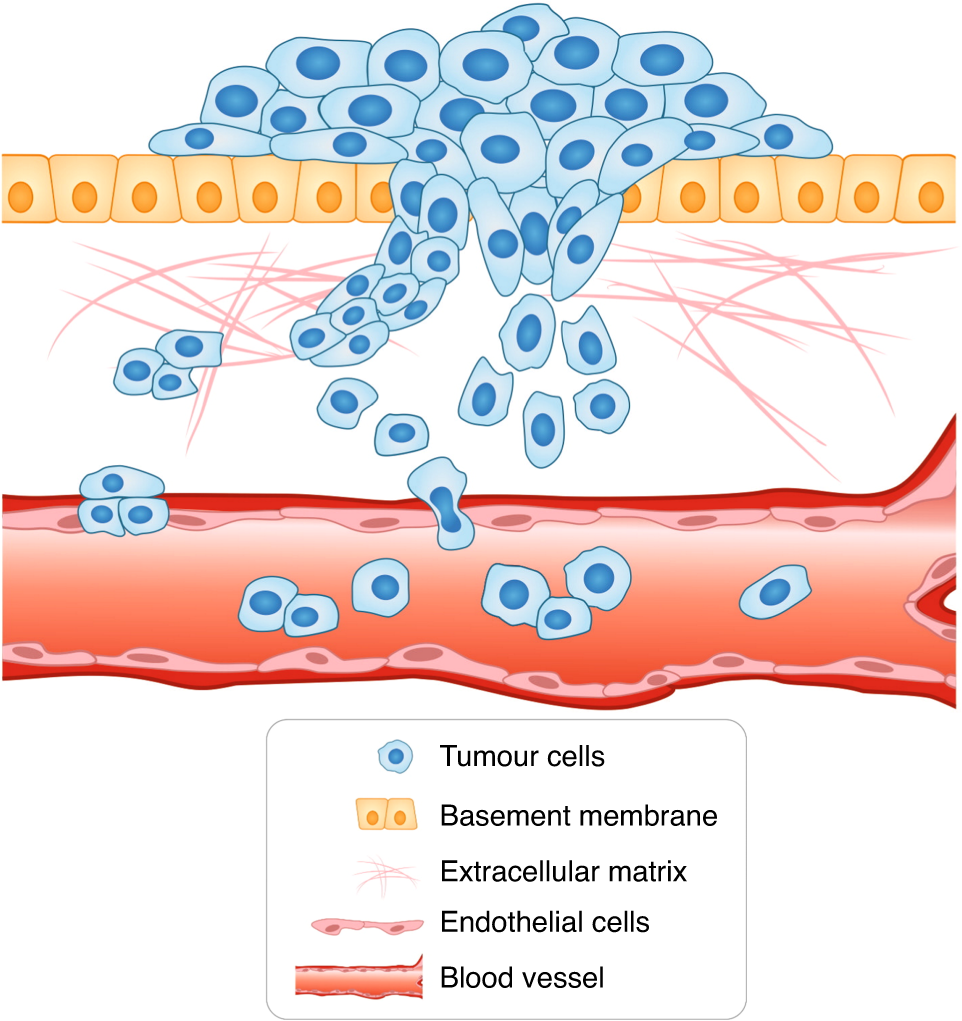

Cancer cells penetrate the basement membrane and invade the surrounding tissues.

Source:

Br J Cancer 124, 102–114 (2021)

The following images show premalignant and malignant disease for the most common causes of U.S. cancer death:

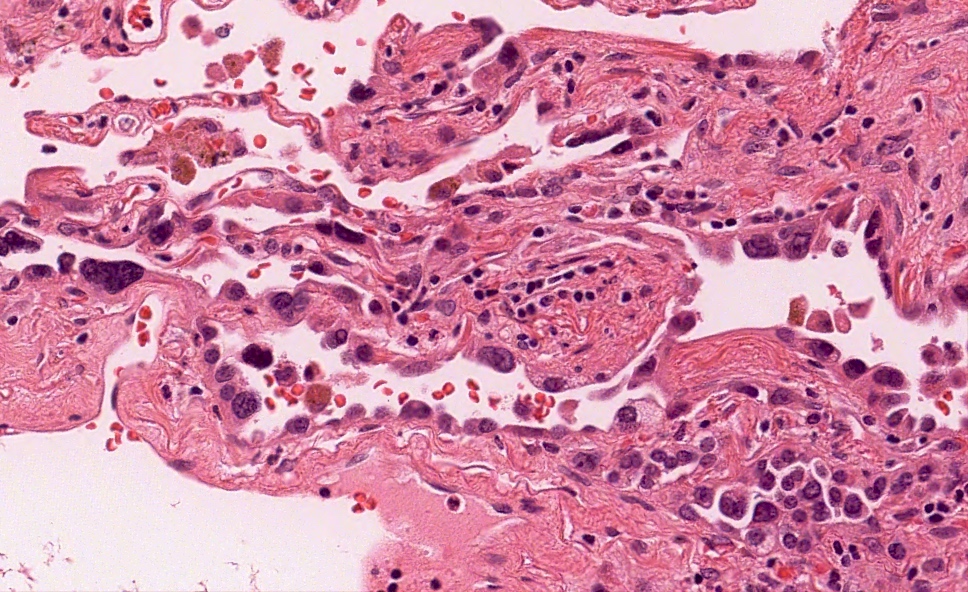

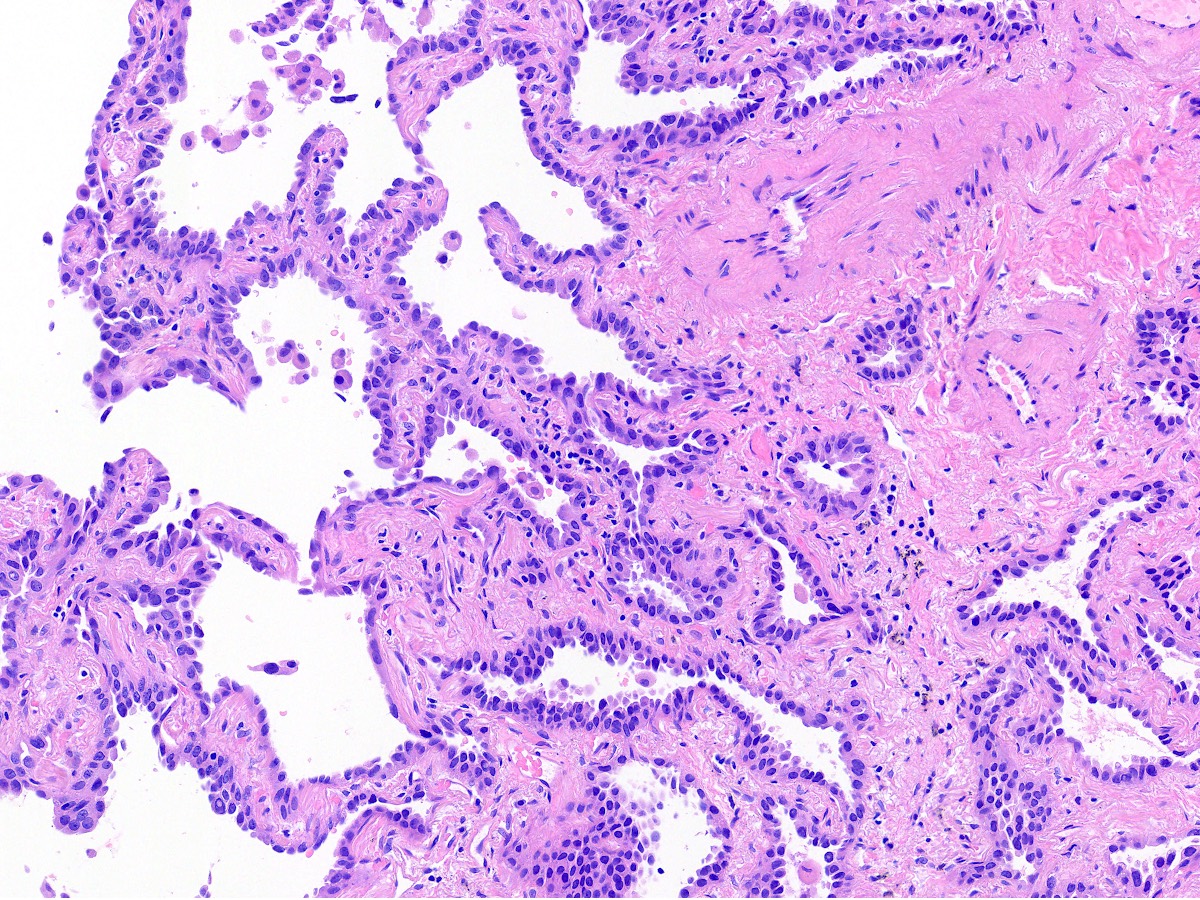

1. Lung cancer: atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (premalignant) and adenocarcinoma (malignant)

1a. Lung - atypical adenomatous hyperplasia: In this premalignant condition, cells lining the alveolar spaces have darkened (hyperchromatic) nuclei and are irregular in shape but have not invaded deeper tissue.

1b. Lung - invasive adenocarcinoma: The left side shows premalignant cells lining intact alveolar spaces. The right side shows malignant, irregular invasive glandular structures with intervening fibrous tissue.

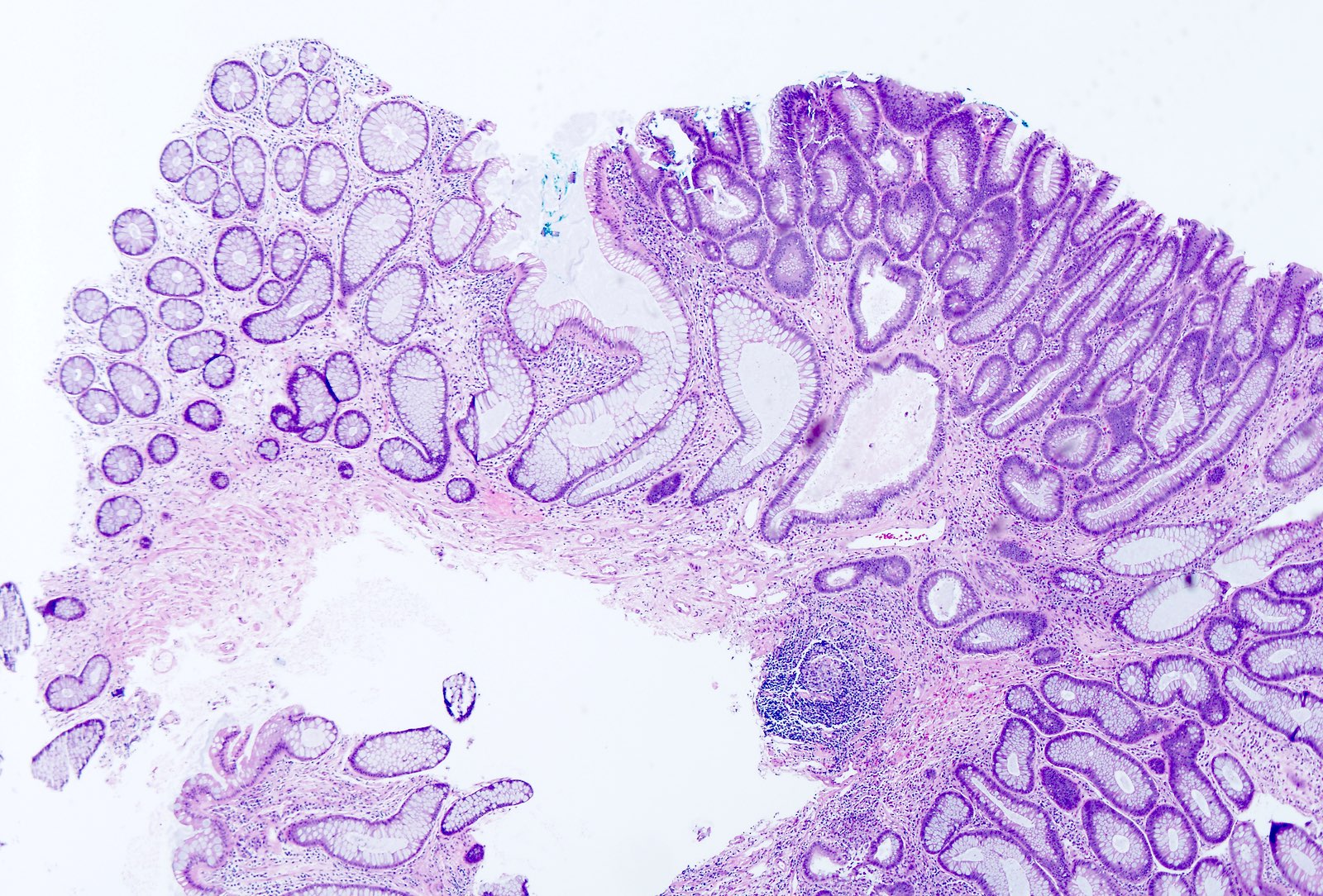

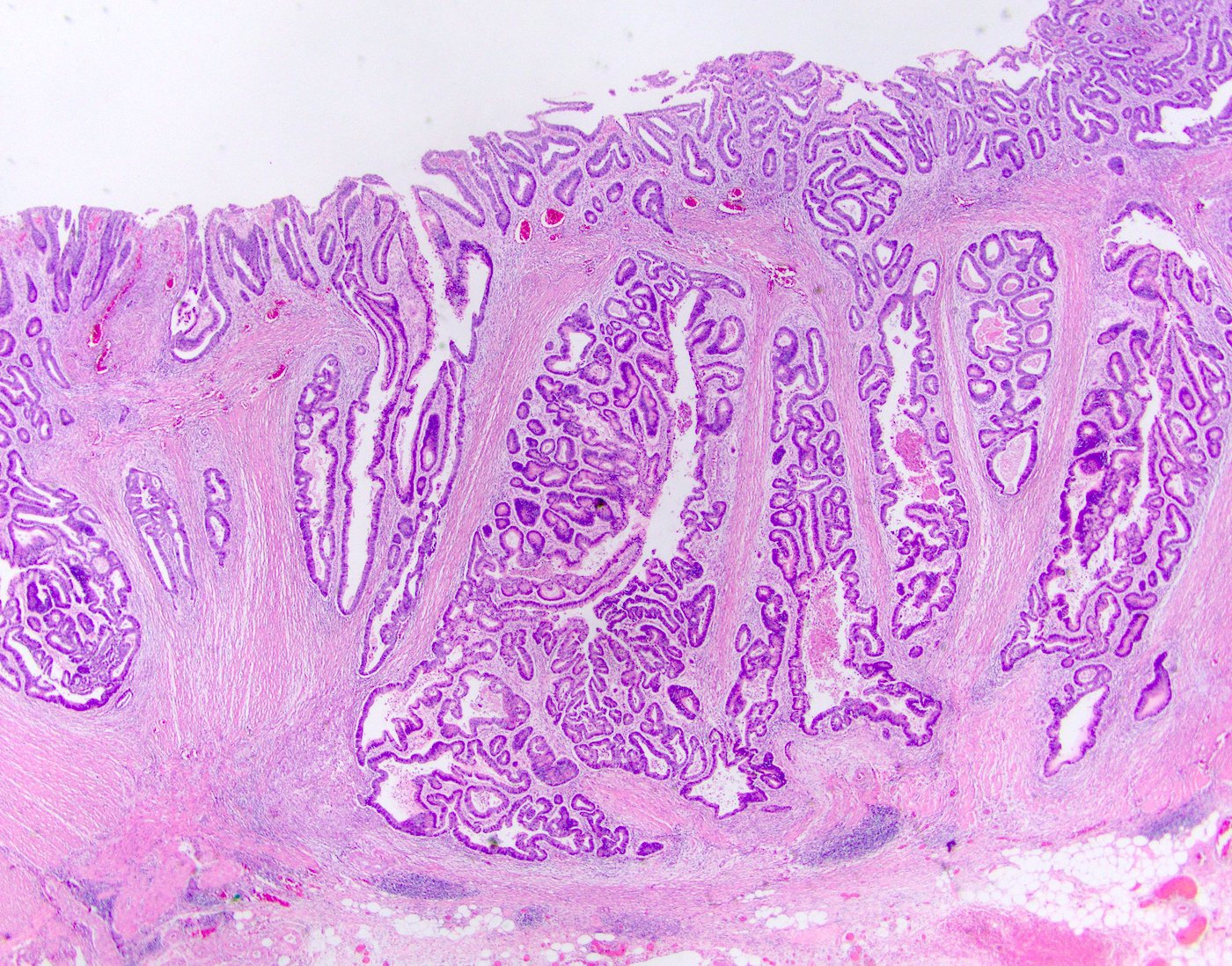

2. Colon cancer: tubular adenoma (premalignant) and adenocarcinoma (malignant)

2a. Colon - tubular adenoma: These 2 images demonstrate this premalignant condition. In the left image, the left side shows normal colonic epithelium and the right side has nuclei that are darker (tubular adenoma). In the right image from a different patient, the nuclei are pseudostratified (i.e., uneven, appearing to be in multiple layers).

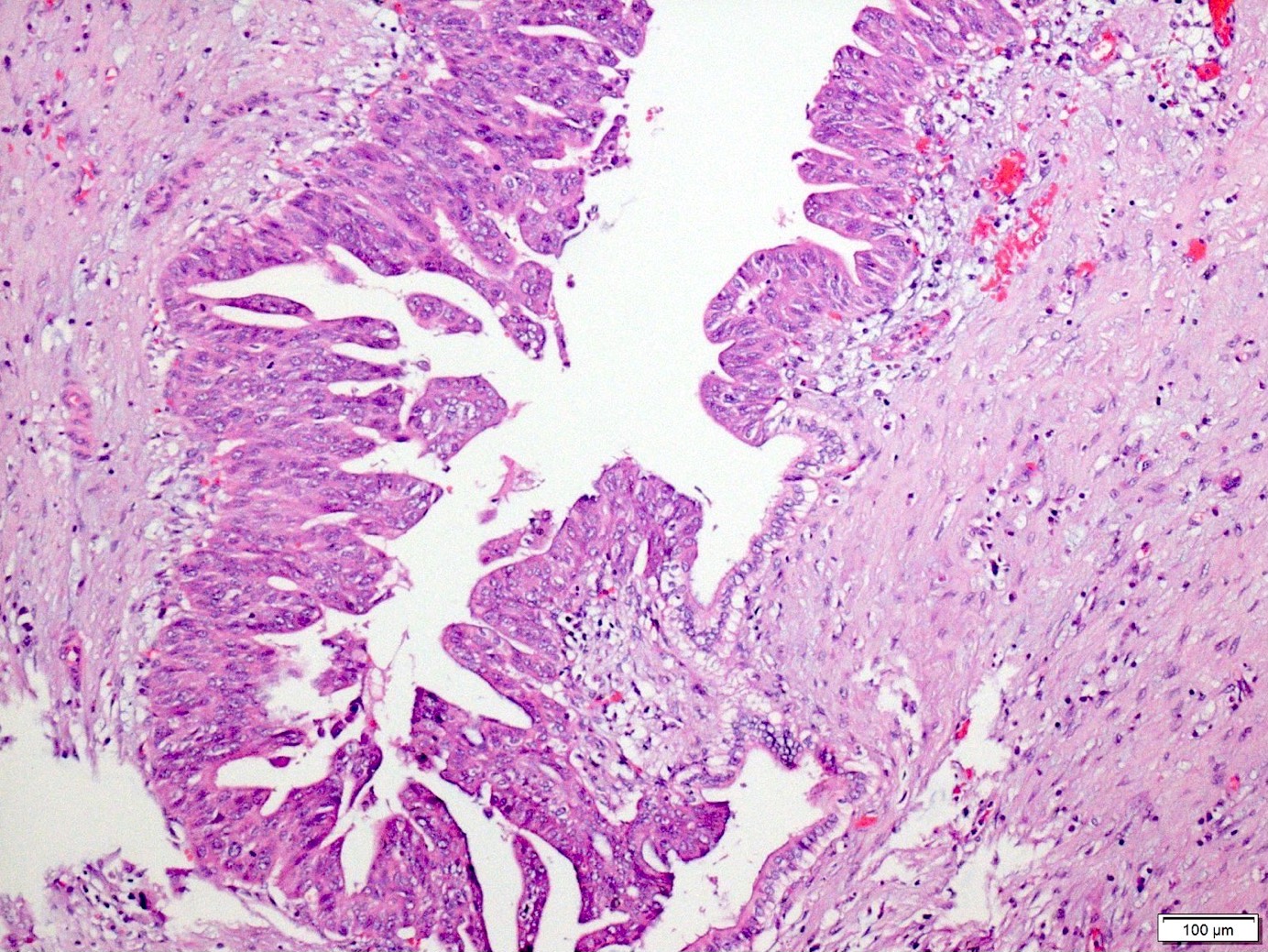

2b. Colon - invasive adenocarcinoma: In this malignant condition, these 2 images from different patients show glands with darkened nuclei and irregular shapes penetrating deep below the surface.

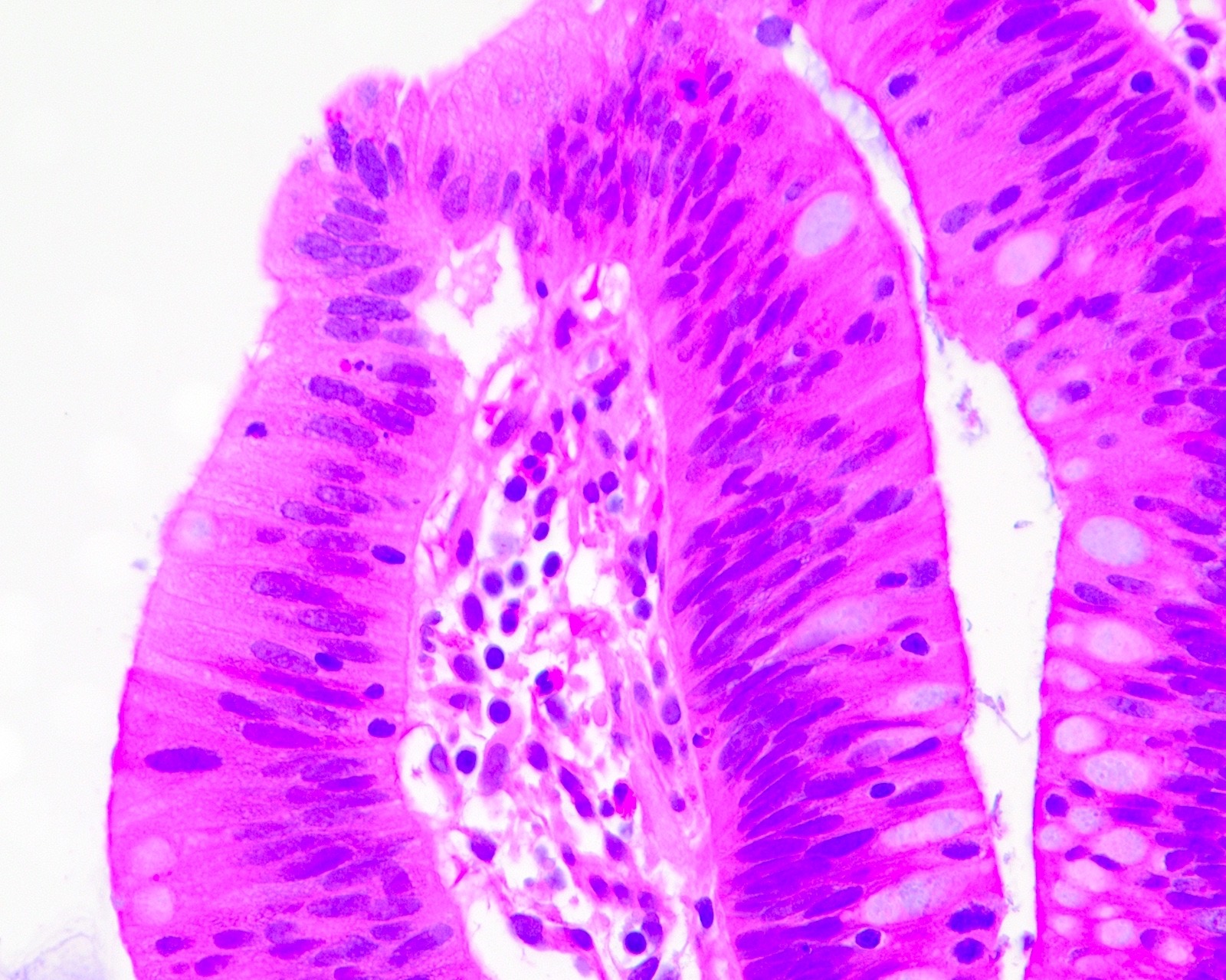

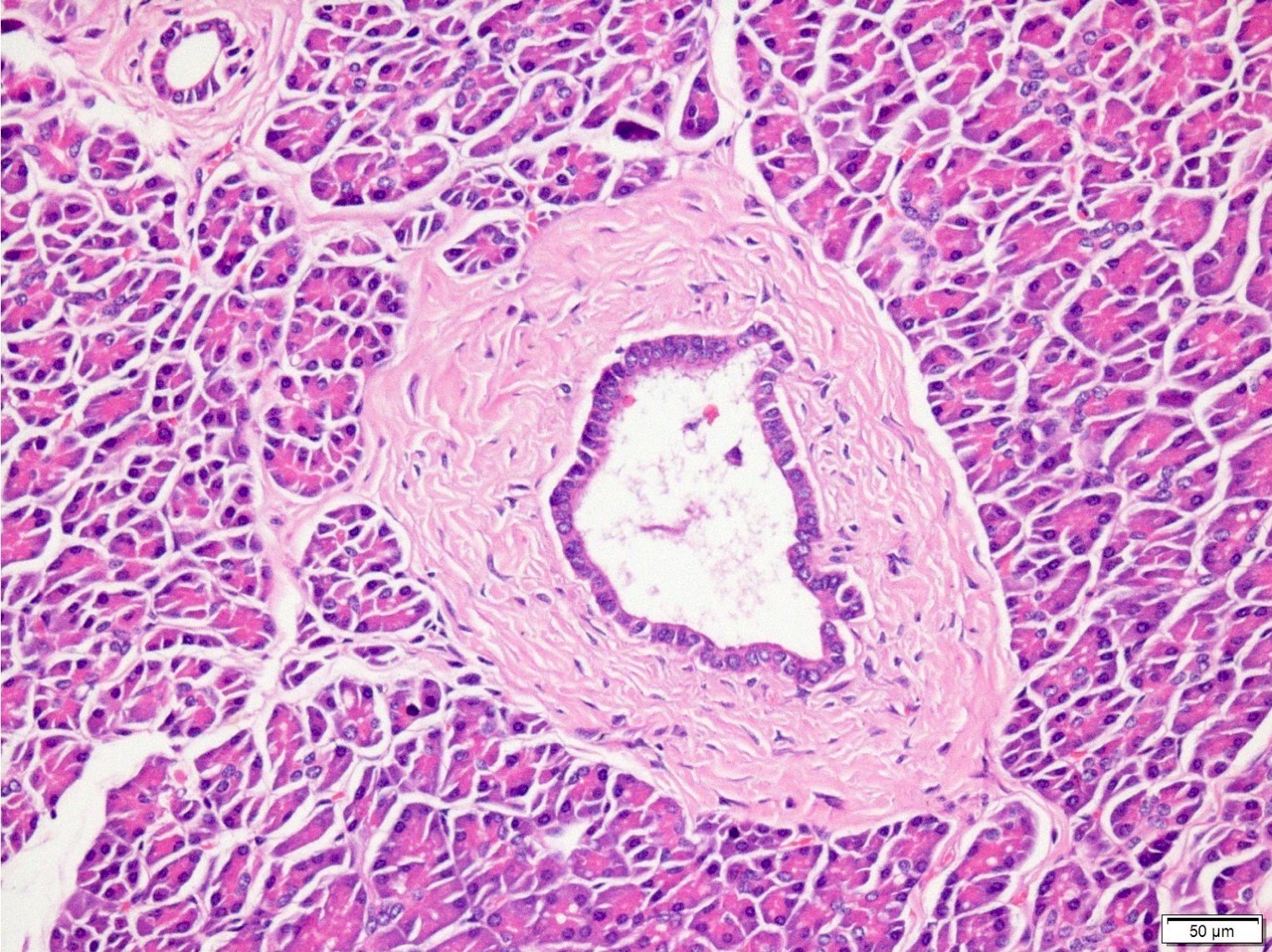

3. Pancreatic cancer: pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN, premalignant) and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma of usual type (malignant)

3a. Normal pancreatic duct in center of image, surrounded by fibrous tissue and normal pancreatic acinar cells.

3a. Pancreas - PanIN: In this premalignant condition, the duct is irregular in shape and the cells have irregular and darkened nuclei (please compare to the normal pancreatic duct on the left).

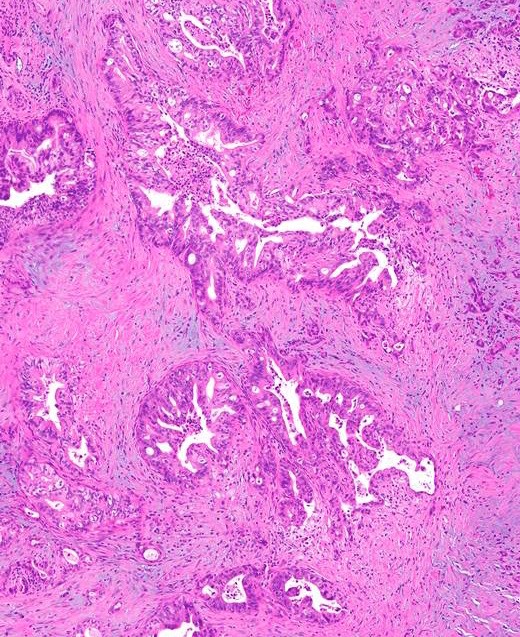

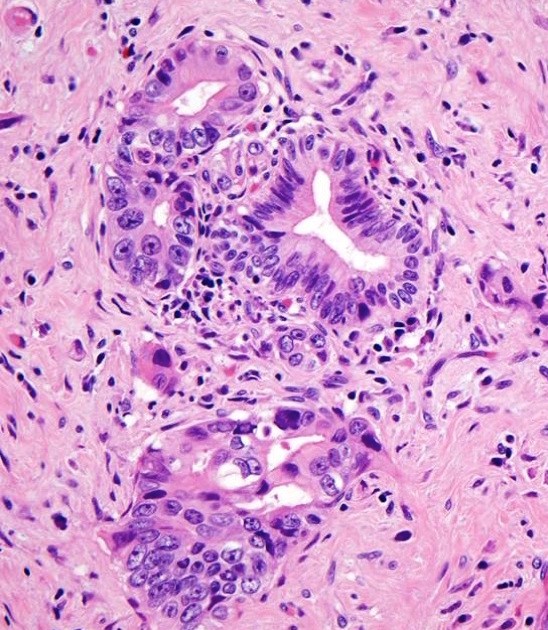

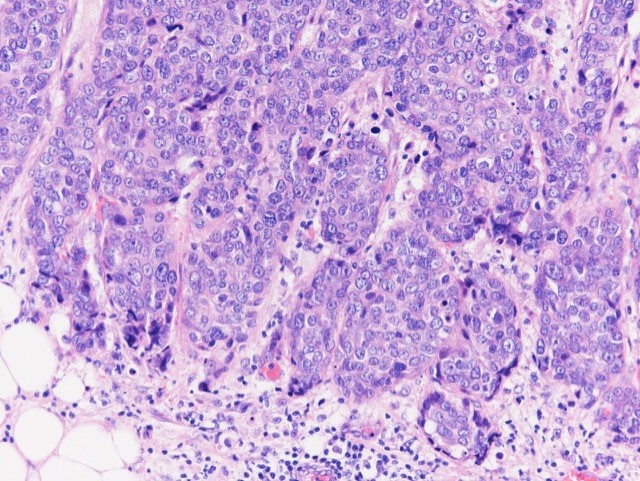

3b. Pancreas - pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: In this malignant condition, these 2 images from different patients show glands with darkened nuclei and irregular shapes penetrating deep below the surface of the pancreas.

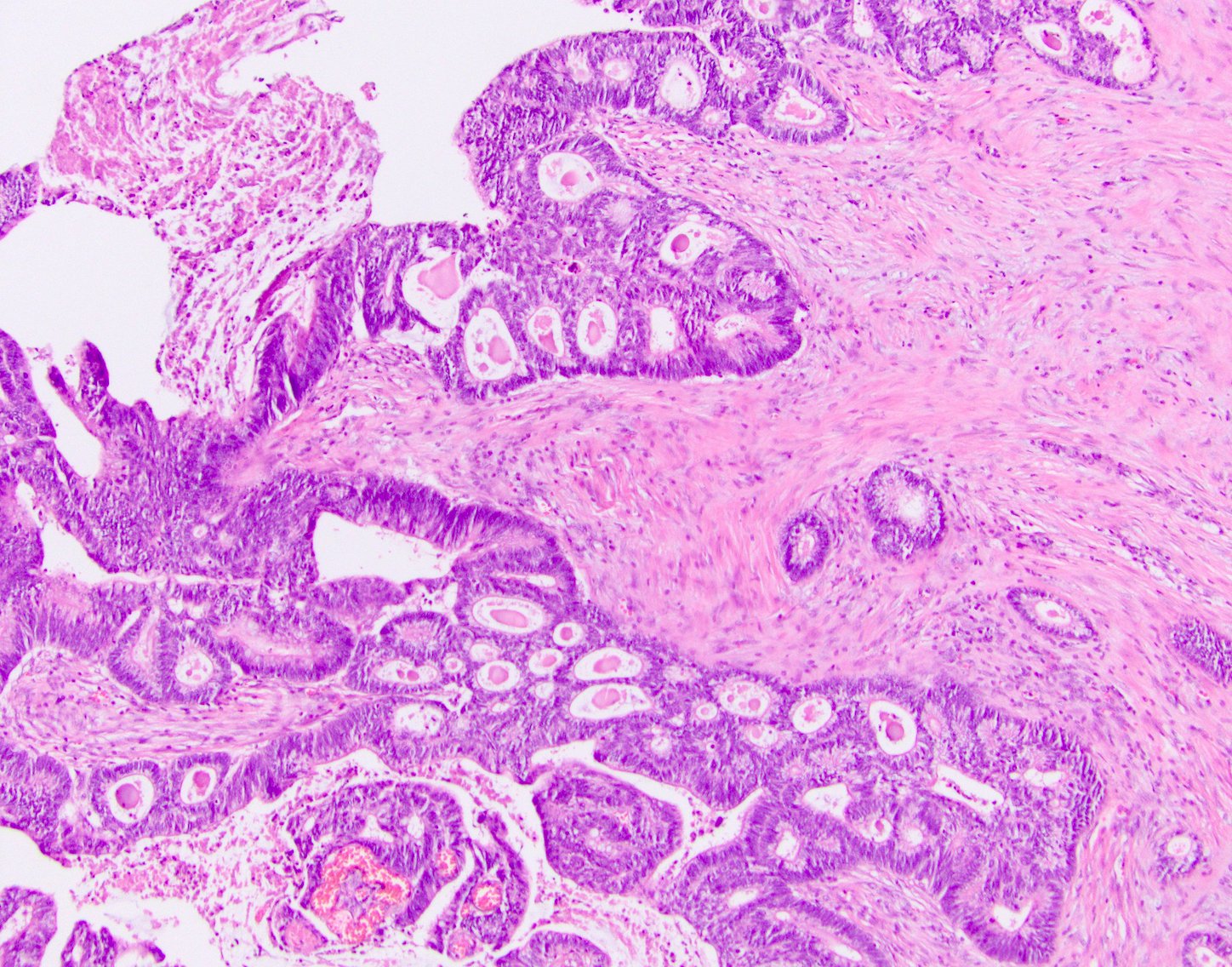

4. Breast cancer: ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS, premalignant) and invasive ductal carcinoma (malignant)

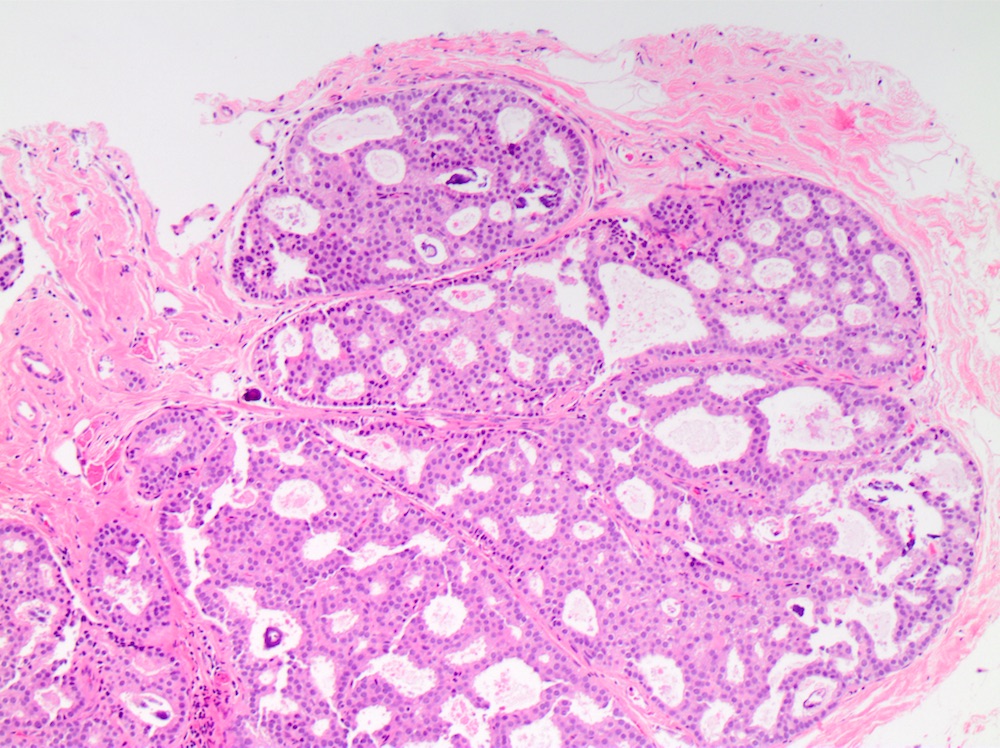

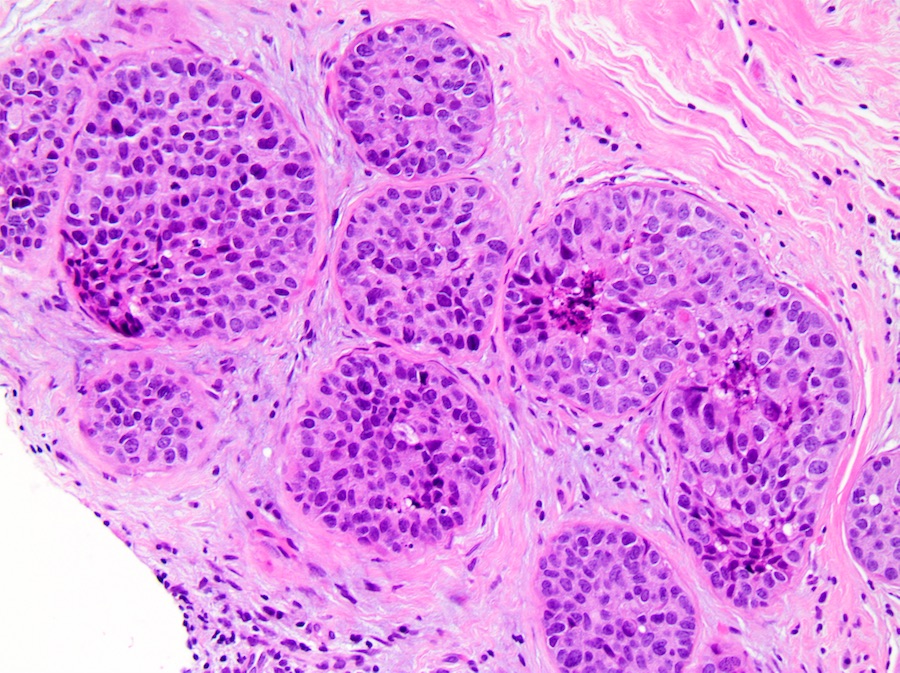

4a. Breast - DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ): In this premalignant condition, the left image shows ducts whose cells are crowded together but look too normal and too uniform for this much crowding. In the right image, DCIS from a different patient, the cells have marked nuclear abnormalities (darkened and irregular nuclei).

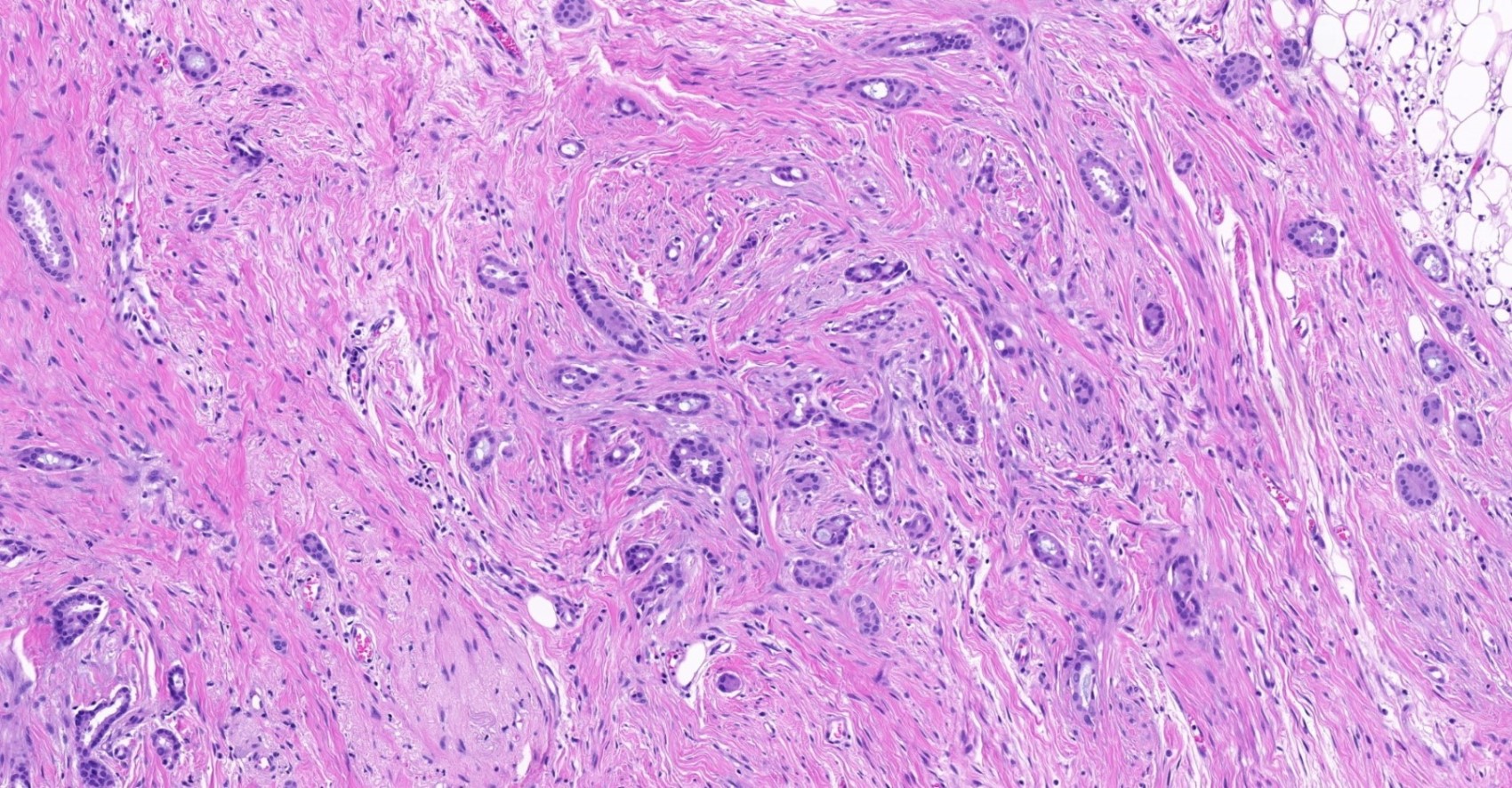

4b. Breast - Ductal adenocarcinoma: In this malignant condition, the left image shows malignant glands scattered throughout the breast tissue. In the right image, at higher power, these cells from a different patient show darker nuclei, irregular shapes and loss of the usual gland-like architecture.

How does tissue change from normal to premalignant to malignant?

We have proposed that malignant change is due to self-organized criticality, nature's way of making enormous transformations over a short time scale based on individual factors often thought too trivial to consider. For example, in a simple sandpile, individual grains of sand dropped on a sandpile usually have no apparent impact, occasionally cause small avalanches and rarely cause the entire sandpile to collapse. Dropping a single grain of sand with no apparent impact causes small structural changes in the sandpile that ultimately may enable an additional grain to set off an avalanche (Bak, How Nature Works 1999).

Similarly, in punctuated equilibrium of species, a theory about the evolution of species, one sees prolonged periods of no new species followed by bursts of new species (Eldredge & Gould 1972). During the "quiet" periods, minor changes are accumulating but are not apparent, as with the sandpile.

Human cellular networks also have long periods with accumulation of minor changes and no apparent clinical or microscopic changes, followed by bursts of activity leading to obvious premalignant or malignant changes (Cross 2016).

The theory of self-organized criticality contrasts with the theory of gradualism, in which major changes occur due to the steady accumulation of small changes that produce visible differences. Gradualism is easily understandable and logical and was promoted by Darwin (Gould 1983) but it does not accurately describe changes to a sandpile, the evolution of species or the process of malignant change (Sun 2018).

Email me at Nat@PathologyOutlines.com with any comments or questions.