Strategic plan to substantially reduce cancer deaths - discussion #6

What we have learned from studying colon cancer

This essay expands on our strategic plan to substantially reduce cancer deaths by discussing what the medical community has learned from studying colon cancer, currently the #2 cause of cancer death in the United States. I have also added my own conclusions, which are not yet part of the medical consensus on this disease.

The American Cancer Society projects that in 2023, colorectal cancer will cause 52,550 deaths in the U.S. (28,470 men, 24,080 women). It is the third leading cause of U.S. cancer death in men (after lung and prostate) and in women (after lung and breast) but is #2 overall because prostate and breast cancer are largely gender restricted. Colon and rectal cancers are reported together because many rectal cancer deaths are misclassified as colon cancer on death certificates, due in part to cultural reluctance to use the term "rectum" (Cancer Facts & Figures 2023).

Colorectal cancer death rates have dropped substantially from 29.2 per 100,000 in 1970 to 12.6 in 2020, attributed to earlier detection through screening and improvements in treatment; however, incidence and death rates for adults under age 55 years (particularly white Americans) have been increasing for unknown reasons (Note: I have not found any graphs that I can legally post but click here, source).

Colorectal cancer death rates, by age, 1999 to 2019

My major conclusions from studying colorectal cancer are

- No single treatment for advanced colon cancer is likely to be curative due to its diverse origins and because aggressive tumors and widespread disease are accompanied by systemic changes different in character from those present in the cancer cells (Pernick: How colorectal cancer arises and treatment approaches, based on complexity theory 2020).

- To attain high cure rates, we propose combining treatment strategies that affect as many aspects of the malignant process as possible, including (1) kill as many tumor cells as possible, using multiple, distinct methods to address tumor cell heterogeneity; (2) target the microenvironment nurturing the tumor (i.e., the vasculature, inflammatory cells and their products and the extracellular matrix or "cellular infrastructure"); (3) counter tumor associated immune system dysfunction; (4) identify and target possible genetic changes associated with tumor promotion at birth; (5) move tumor cells that survive treatment toward less hazardous states; (6) identify, reduce and counter the effects of patient related chronic stressors or risk factors; (7) eliminate premalignant lesions through more effective screening; (8) promote overall patient health. This may mean that treatment requires 8-10 therapies, or possibly more, that will have to be timed appropriately to be tolerable and effective.

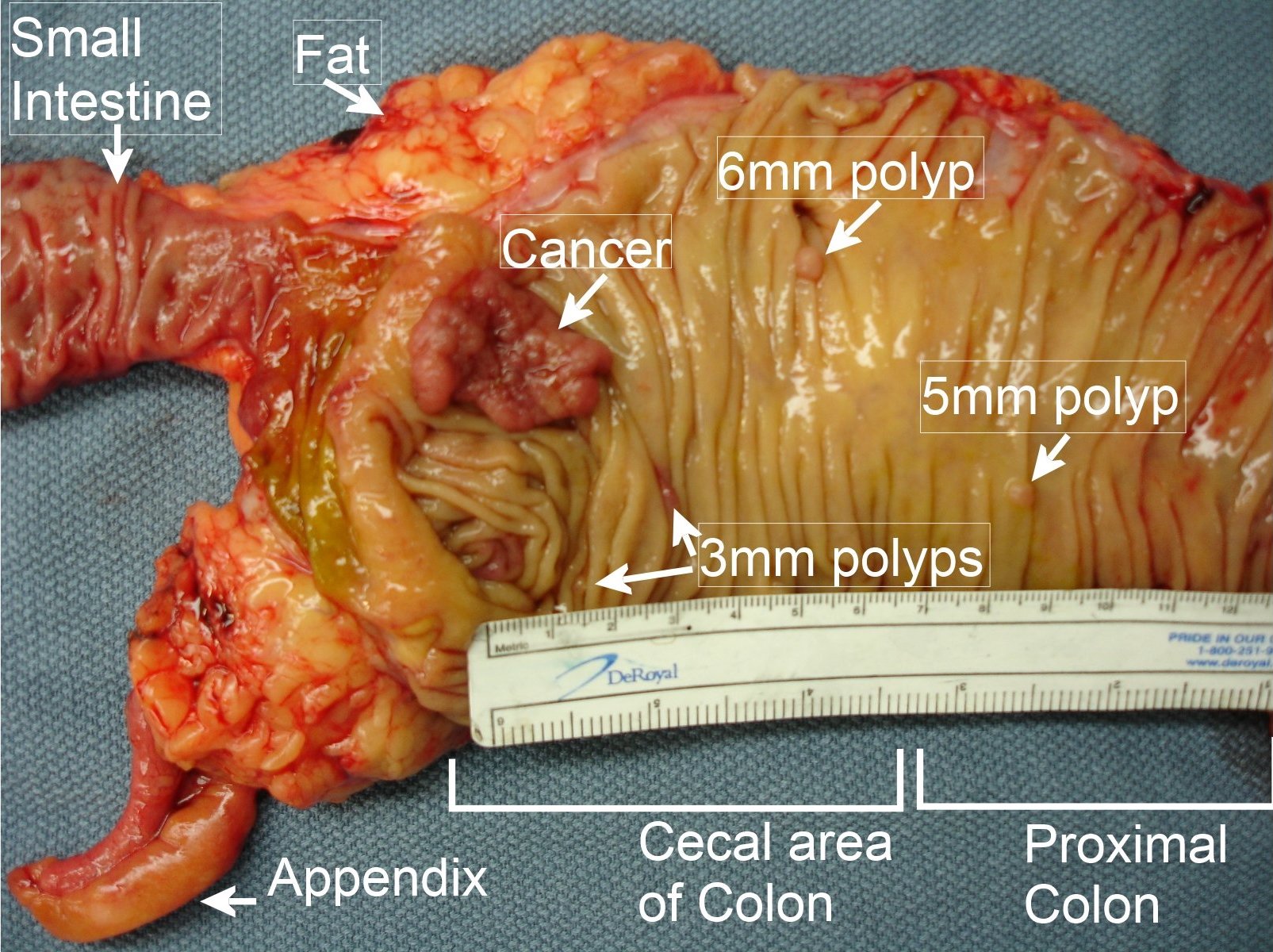

- An important risk factor for colorectal cancer is nonuse of screening, which causes 22% of colorectal cancer cancers and 33% of deaths. Failure to screen is a risk factor because screening detects premalignant and early malignant disease (which is easier to treat); additionally, some screening methods (sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy) remove precancerous adenomas (polyps) and are actually effective treatments themselves. The American Cancer Society and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend that individuals at average risk for colorectal cancer begin screening at age 45 and continue through age 75; however, U.S. screening is suboptimal among underserved populations including the uninsured, recent immigrants and racial/ethnic minority groups; younger adults are also not effectively screened.

- Other risk factors for colorectal cancer and the percentage of colorectal cancer deaths attributed to them (population attributable fraction) are

- Physical inactivity: 16%

- Excess weight (BMI of 25+): 10-20%

- Tobacco: 10%

- Alcohol: 10%

- Diet: 5-10%

- Advancing age is an important risk factor for colorectal cancer; 90% of cases are diagnosed after age 50 years.

- We should aggressively enroll patients into clinical trials so physicians can learn and improve treatment for aggressive disease. Clinical trials are also necessary to determine the optimal timing of the multiple types of treatments that we believe are necessary to cure advanced disease.

The next essay will discuss what we have learned from studying pancreatic cancer.