5 September 2018 - Case of the Week #463

All cases are archived on our website. To view them sorted by case number, diagnosis or category, visit our main Case of the Week page. To subscribe or unsubscribe to Case of the Week or our other email lists, click here.

Thanks to Drs. K.V. Vinu Balraam and S. Venkatesan, Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra (India) for contributing this case and Dr. Genevieve M. Crane, Ph.D., Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (USA) for writing the discussion. To contribute a Case of the Week, first make sure that we are currently accepting cases, then follow the guidelines on our main Case of the Week page.

Advertisement

Website news:

(1) We have updated the Mobile home page to make it easier to use. Click on Chapters by Subspecialty to see a drop down list of subspecialties, each with their own relevant drop-down list of chapters. Currently about 40% of our visits are from users of mobile devices.

(2) We don't have an App for the Board Review Questions, but we have structured the page so it looks something like an App. Bookmark this page on your mobile device and you can easily search our 450+ Board Review style questions by Subspecialty or by Textbook Chapter. We add about 25 questions per month.

If you have comments about a question / answer, click on the Comment feature in the footer and let us know.

(3) We now provide a list of Pathology Residency Directors on the Jobs page and Fellowship Directors on the Fellowships page, in their respective blue boxes. We have intentionally omitted email addresses. When you click on the link, you can download the files as Excel spreadsheets. We will post updates from the programs and will review the list every 6 months. Contact us with changes at CommentsPathOut@gmail.com

Visit and follow our Blog to see recent updates to the website.

Case of the Week #463

Clinical history:

A 9 year old boy presented with anorexia for 2 months and abdominal distension for 8 days. He was febrile (100.4°F) and pale with generalized firm lymphadenopathy. His liver was palpable 2 cm below the right subcostal margin and his spleen was palpable 24 cm below the left subcostal margin extending to the right iliac fossa (Hackett’s Grade 5 splenomegaly).

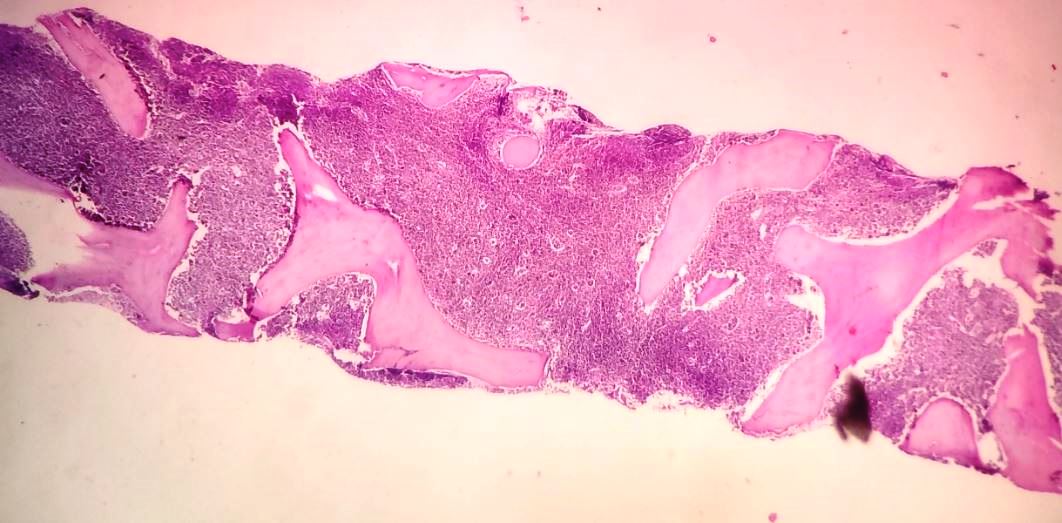

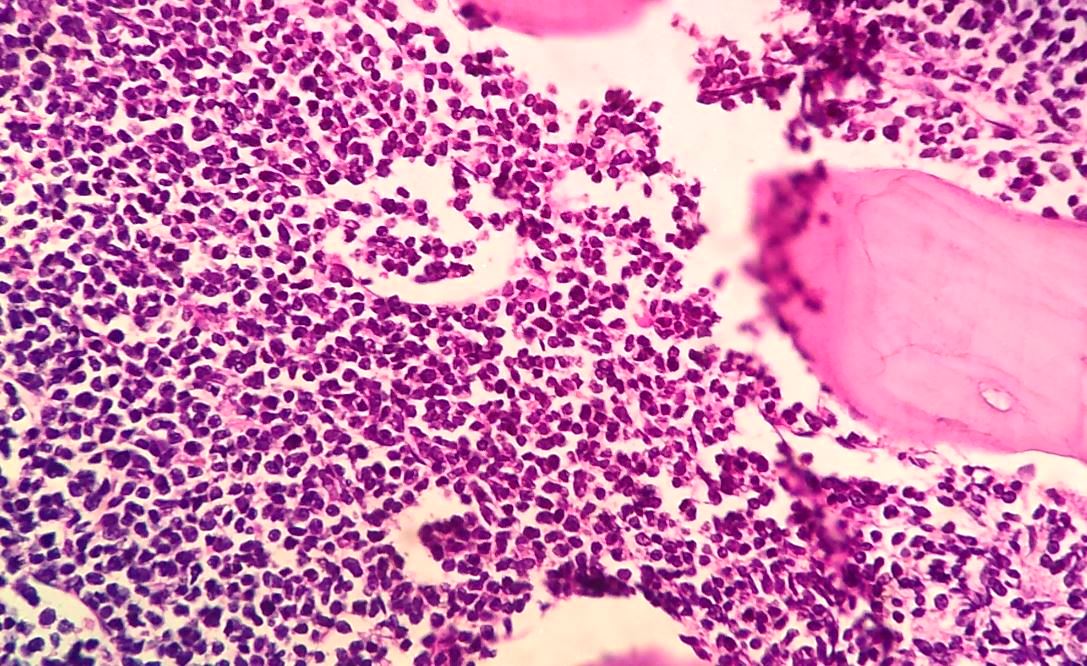

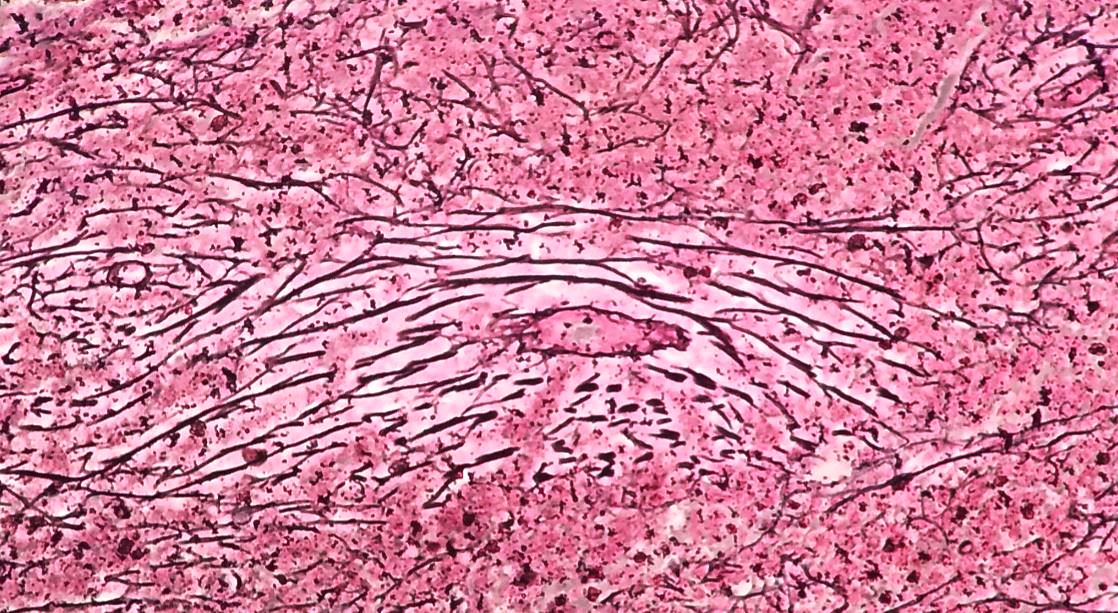

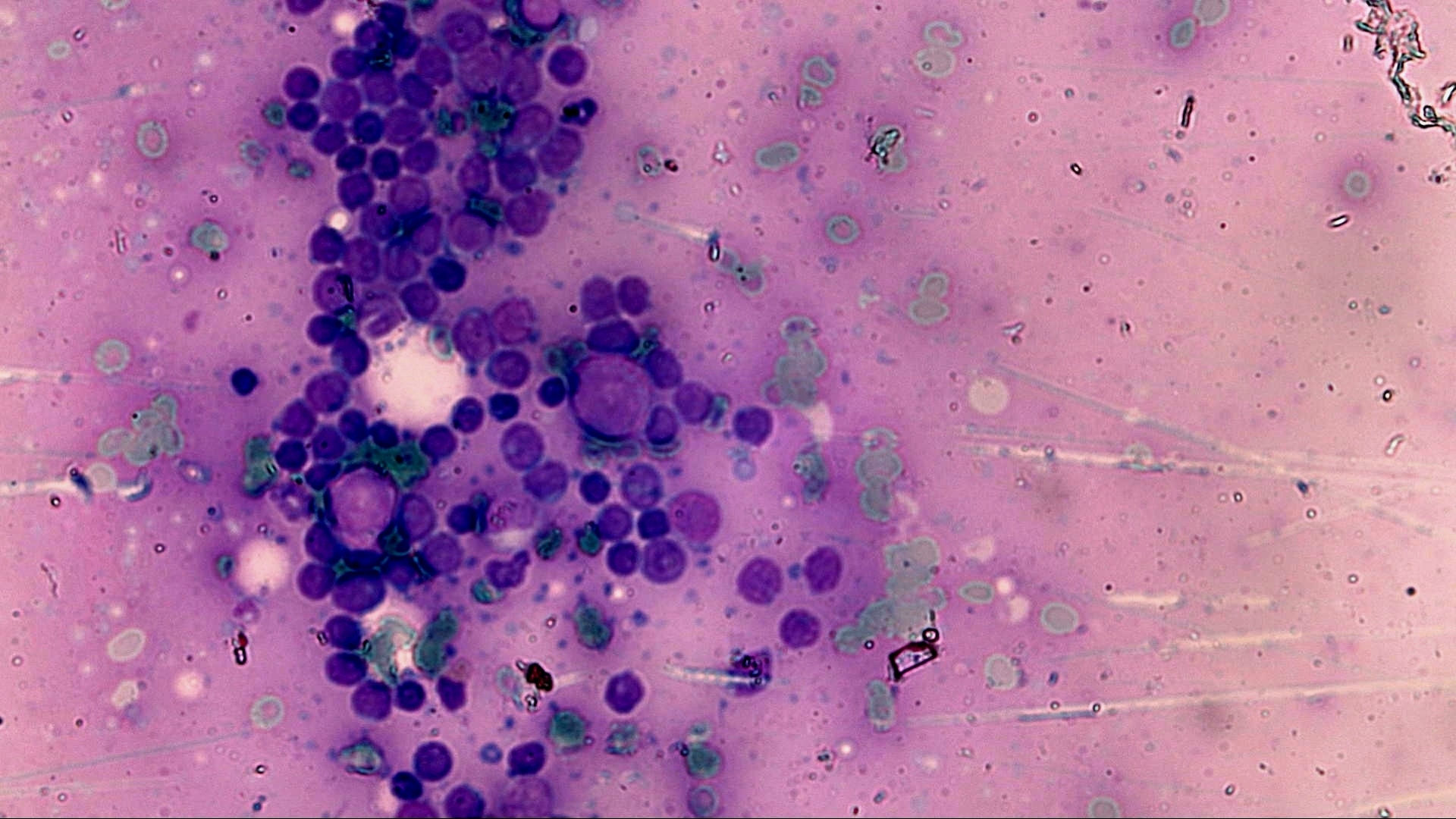

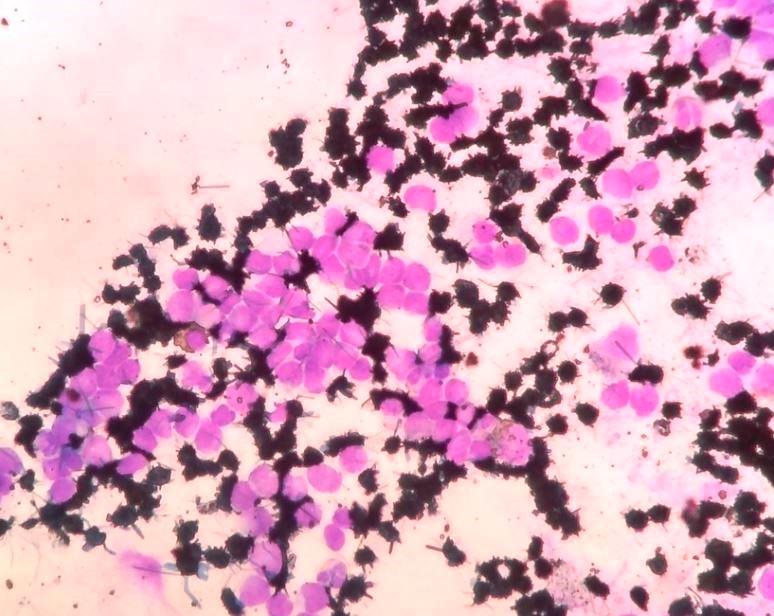

Bone marrow biopsy:

Bone marrow evaluation aspirate and touch preps demonstrated 72% blasts. The biopsy demonstrated 100% cellularity with sheets of blasts and focally increased reticulin fibrosis.

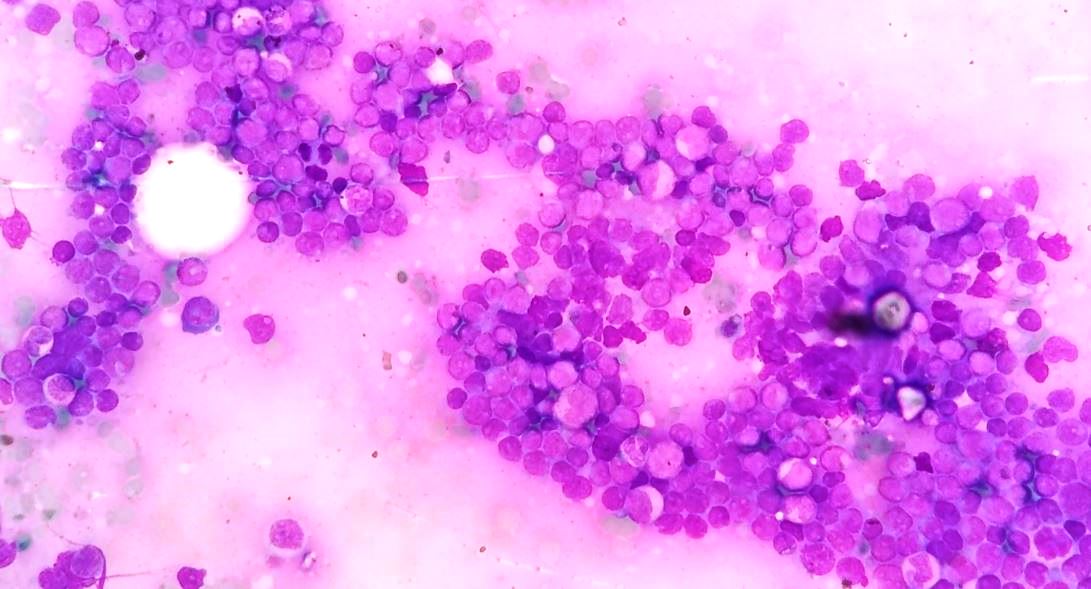

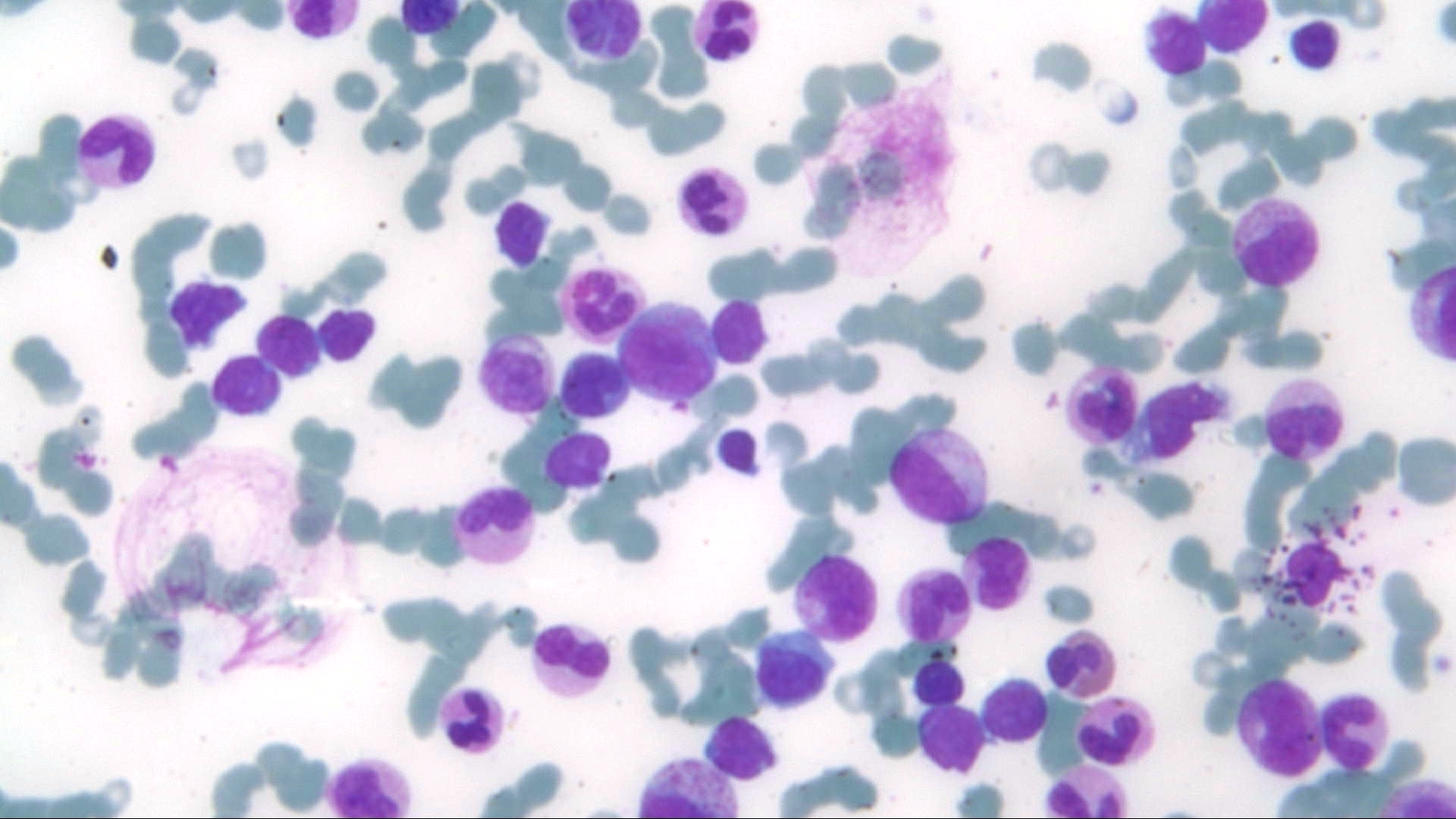

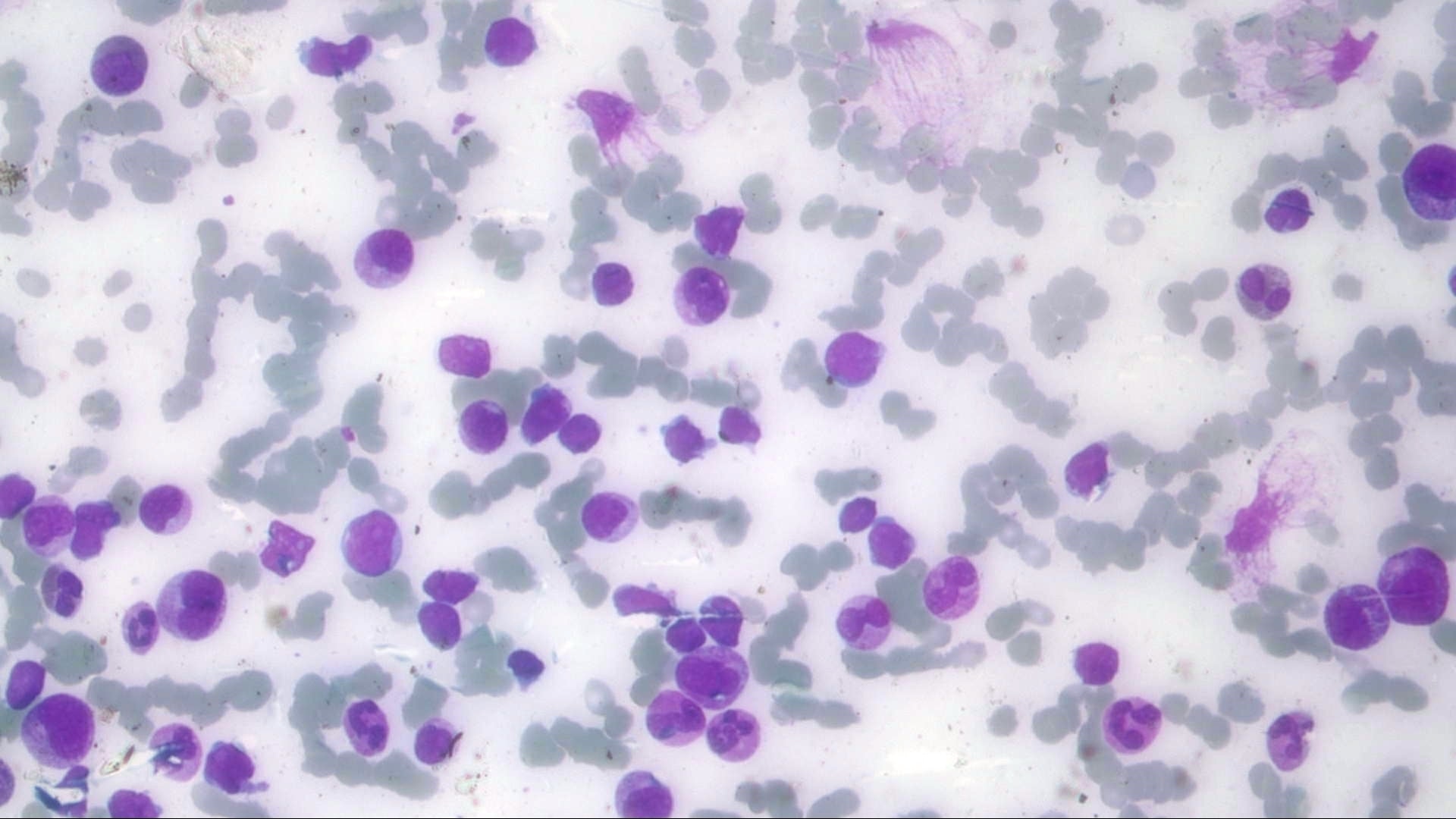

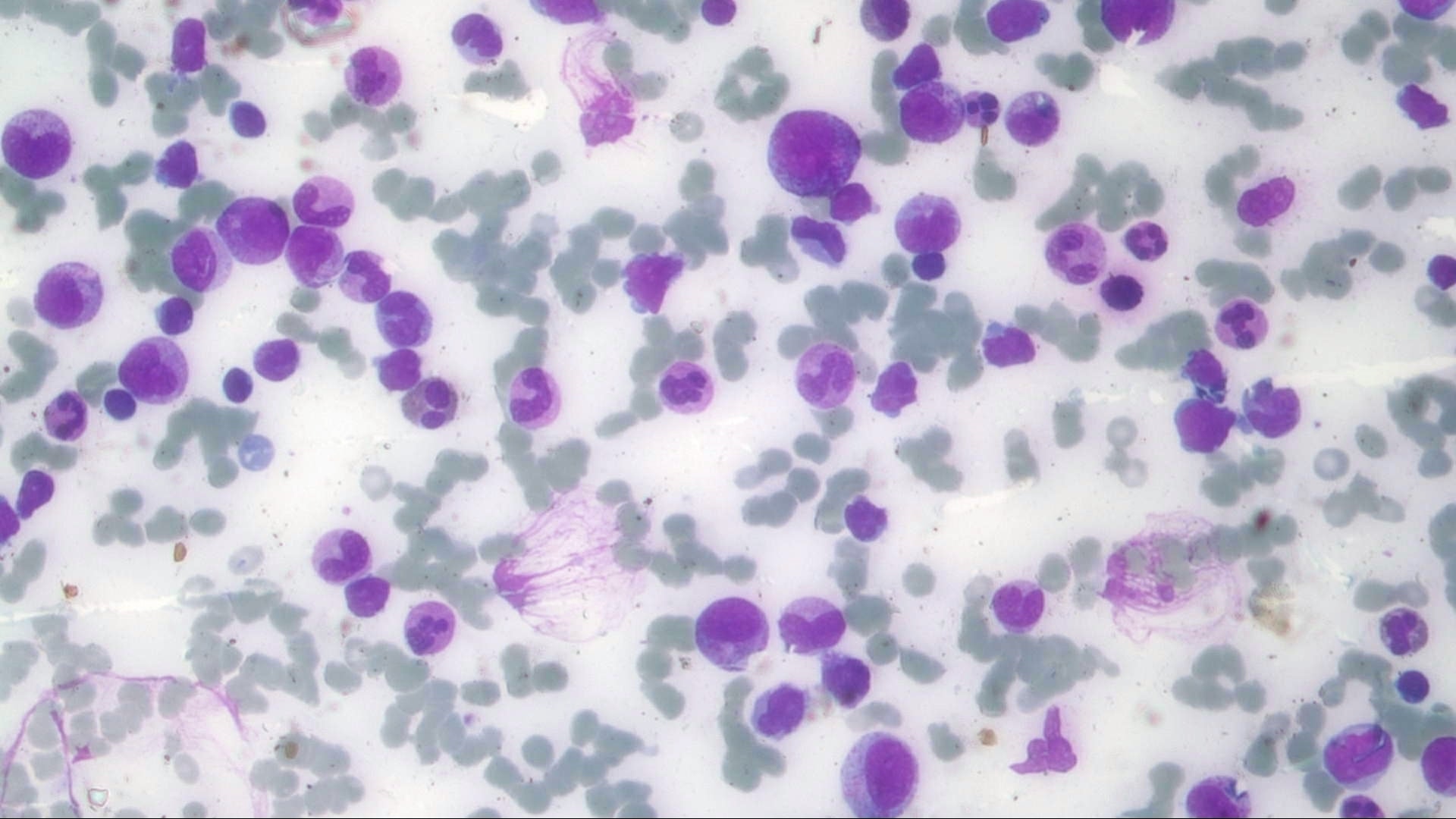

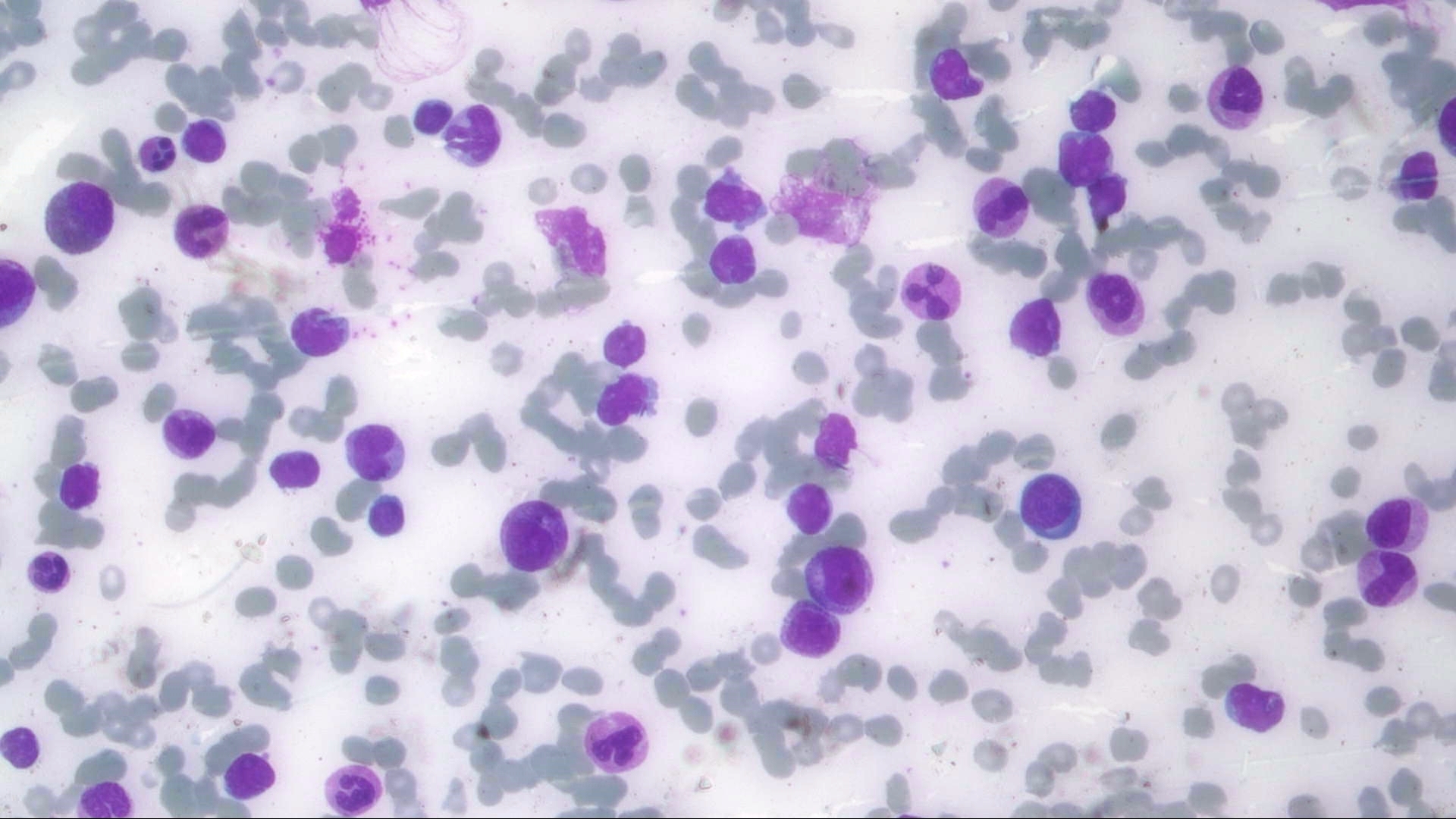

Peripheral blood images:

The peripheral blood demonstrated normocytic, normochromic anemia (Hb 8 g/dL), with an elevated white blood cell count of 239 x109/L. A differential count demonstrated 25% blasts, 17% myelocytes, 10% lymphocytes, 2% monocytes, 5% eosinophils and 3% basophils. The blasts demonstrated a high N:C ratio with fine chromatin, 1-2 prominent nucleoli and scant basophilic cytoplasm. The blasts were agranular, and no Auer rods were seen.

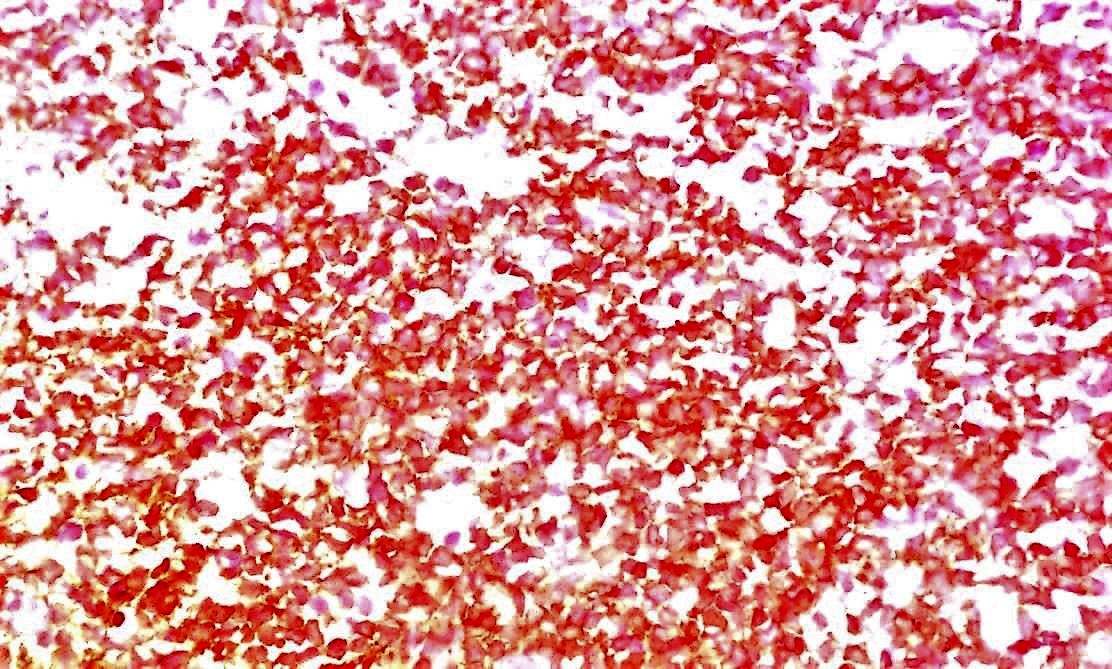

Special stains and IHC:

The blasts were negative for myeloperoxidase by cytochemical and immunohistochemical staining. Additional immunohistochemical stains demonstrated they were positive for CD34, CD19, CD79a and CD10. They were negative for C117 and CD3.

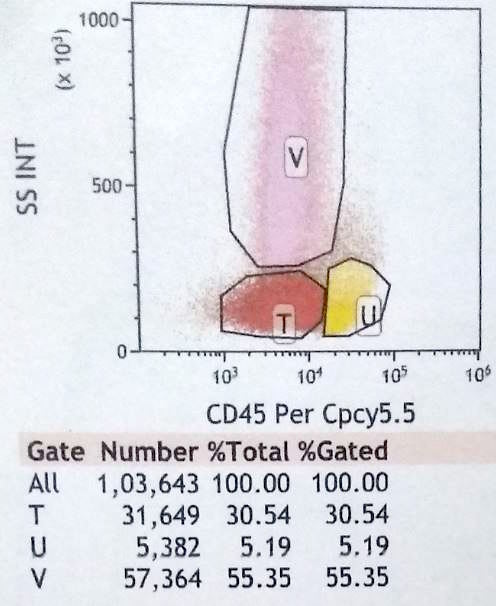

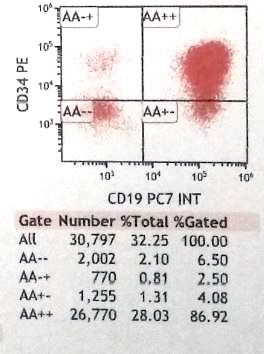

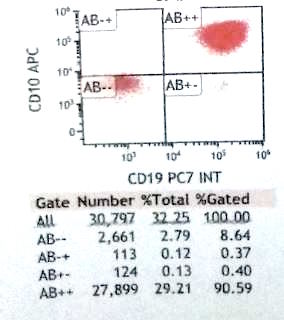

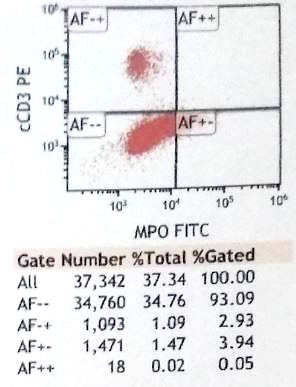

Flow cytometry images:

Flow cytometric analysis of the peripheral blood demonstrated 30% blasts expressing CD45 (dim), CD34, CD19, CD10, CD20, CD79a, CD38 and HLA-DR. The blasts were negative for CD13, C117, MPO, CD56, CD2, cCD3, CD5, CD7, CD14, CD15, CD33, CD64 and CD36.

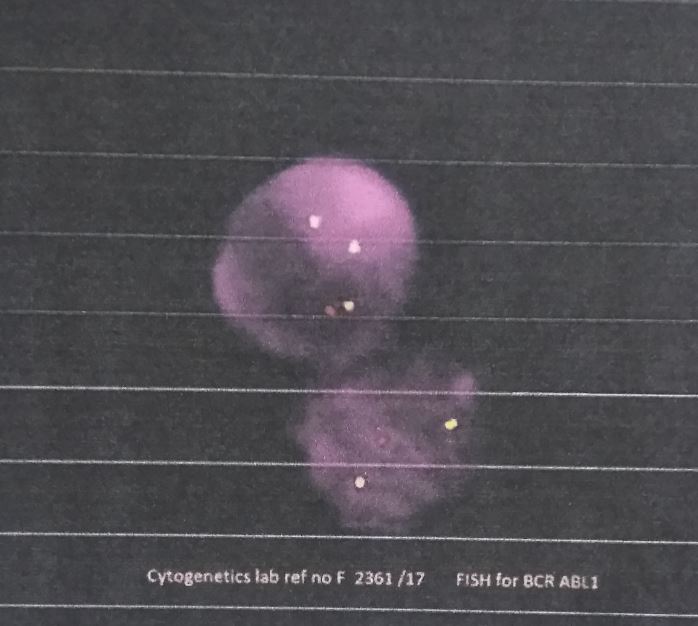

Cytogenetic image:

Interphase FISH demonstrated BCR-ABL1 fusion positivity in 98% of cells. Occasional maturing myeloid cells present in the smears studied also showed BCR-ABL1 positivity.

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis:

B cell lymphoid blast crisis in a case of pediatric CML at presentation

Test question (answer at the end):

Which of these features is true of adult patients with CML when compared with pediatric patients with CML?

A. Higher white blood cell count at initial presentation.

B. More likely to obtain deep molecular response with imatinib tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.

C. More likely to present in accelerated or blast phase.

D. More likely to have splenomegaly.

Discussion:

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is rare in the pediatric age group, accounting for 2% of childhood leukemias in children younger than 15 years and 9% of leukemias in adolescents between 15 and 19 years (Blood 2016;127:392). The median age is 11 years with an overall incidence of approximately 1-2 per million children per year (Br J Haematol 2014;167:33). Pediatric patients tend to present with a higher white blood cell count (median ~250 x109/L) compared with CML arising in the adult population (Blood 2012;120:3741) and have a more aggressive course. In addition, the proportion of pediatric patients diagnosed with advanced stage disease, i.e. accelerated phase or blast phase, is higher than seen in adult patients (Blood 2016;127:392). They tend to show a different distribution of the breakpoint region, more similar to that seen in the adult population who develop BCR-ABL+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012;51:1045). They may also have a lower rate of molecular remission with imatinib compared with adult patients, although response with second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be higher and remains under study.

Blast phase is defined as ≥ 20% blasts in the blood or bone marrow or the presence of extramedullary proliferations of blasts. In most of the cases the blasts are myeloid, but in 20-30% of cases they are lymphoblasts. These are predominantly B lymphoblasts, but T and NK blast populations have also been reported (WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Revised 4th Edition, 2017).

In this case, it was also important to differentiate a lymphoid blast crisis arising from CML from B acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL), which also occurs in the pediatric population and can be associated with BCR-ABL1 fusion. However, the t(9;22)(q34.1;q11.2) BCR-ABL fusion is relatively rare in pediatric cases of B-ALL, accounting for only 2-4% of pediatric cases compared with 25% of adult B-ALL (WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Revised 4th Edition, 2017). While there are increased immature myeloid elements in the peripheral blood, this may happen in the setting of any process in which the bone marrow is infiltrated. The presence of the BCR-ABL1 fusion in more differentiated myeloid elements favors CML as the underlying process. Mixed phenotype acute leukemia may also occur de novo or arising from CML. Here, however, there was not an increased myeloid blast population. B-ALL with BCR-ABL1, blast or accelerated phase CML and chronic phase CML all benefit from tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.

Test question answer:

B. Adult patients with CML are more likely to achieve remission with imatinib therapy. Whether children may respond better to second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors is under investigation. Pediatric patients presenting with CML tend to have a higher white blood cell count and are more likely to present in accelerated or blast phase than their adult counterparts. Both populations often present with splenomegaly, but it may be more noticeable in children.

All cases are archived on our website. To view them sorted by case number, diagnosis or category, visit our main Case of the Week page. To subscribe or unsubscribe to Case of the Week or our other email lists, click here.

Thanks to Drs. K.V. Vinu Balraam and S. Venkatesan, Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra (India) for contributing this case and Dr. Genevieve M. Crane, Ph.D., Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (USA) for writing the discussion. To contribute a Case of the Week, first make sure that we are currently accepting cases, then follow the guidelines on our main Case of the Week page.

Advertisement

Website news:

(1) We have updated the Mobile home page to make it easier to use. Click on Chapters by Subspecialty to see a drop down list of subspecialties, each with their own relevant drop-down list of chapters. Currently about 40% of our visits are from users of mobile devices.

(2) We don't have an App for the Board Review Questions, but we have structured the page so it looks something like an App. Bookmark this page on your mobile device and you can easily search our 450+ Board Review style questions by Subspecialty or by Textbook Chapter. We add about 25 questions per month.

If you have comments about a question / answer, click on the Comment feature in the footer and let us know.

(3) We now provide a list of Pathology Residency Directors on the Jobs page and Fellowship Directors on the Fellowships page, in their respective blue boxes. We have intentionally omitted email addresses. When you click on the link, you can download the files as Excel spreadsheets. We will post updates from the programs and will review the list every 6 months. Contact us with changes at CommentsPathOut@gmail.com

Visit and follow our Blog to see recent updates to the website.

Case of the Week #463

Clinical history:

A 9 year old boy presented with anorexia for 2 months and abdominal distension for 8 days. He was febrile (100.4°F) and pale with generalized firm lymphadenopathy. His liver was palpable 2 cm below the right subcostal margin and his spleen was palpable 24 cm below the left subcostal margin extending to the right iliac fossa (Hackett’s Grade 5 splenomegaly).

Bone marrow biopsy:

Bone marrow evaluation aspirate and touch preps demonstrated 72% blasts. The biopsy demonstrated 100% cellularity with sheets of blasts and focally increased reticulin fibrosis.

Peripheral blood images:

The peripheral blood demonstrated normocytic, normochromic anemia (Hb 8 g/dL), with an elevated white blood cell count of 239 x109/L. A differential count demonstrated 25% blasts, 17% myelocytes, 10% lymphocytes, 2% monocytes, 5% eosinophils and 3% basophils. The blasts demonstrated a high N:C ratio with fine chromatin, 1-2 prominent nucleoli and scant basophilic cytoplasm. The blasts were agranular, and no Auer rods were seen.

Special stains and IHC:

The blasts were negative for myeloperoxidase by cytochemical and immunohistochemical staining. Additional immunohistochemical stains demonstrated they were positive for CD34, CD19, CD79a and CD10. They were negative for C117 and CD3.

Flow cytometry images:

Flow cytometric analysis of the peripheral blood demonstrated 30% blasts expressing CD45 (dim), CD34, CD19, CD10, CD20, CD79a, CD38 and HLA-DR. The blasts were negative for CD13, C117, MPO, CD56, CD2, cCD3, CD5, CD7, CD14, CD15, CD33, CD64 and CD36.

Cytogenetic image:

Interphase FISH demonstrated BCR-ABL1 fusion positivity in 98% of cells. Occasional maturing myeloid cells present in the smears studied also showed BCR-ABL1 positivity.

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis:

B cell lymphoid blast crisis in a case of pediatric CML at presentation

Test question (answer at the end):

Which of these features is true of adult patients with CML when compared with pediatric patients with CML?

A. Higher white blood cell count at initial presentation.

B. More likely to obtain deep molecular response with imatinib tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.

C. More likely to present in accelerated or blast phase.

D. More likely to have splenomegaly.

Discussion:

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is rare in the pediatric age group, accounting for 2% of childhood leukemias in children younger than 15 years and 9% of leukemias in adolescents between 15 and 19 years (Blood 2016;127:392). The median age is 11 years with an overall incidence of approximately 1-2 per million children per year (Br J Haematol 2014;167:33). Pediatric patients tend to present with a higher white blood cell count (median ~250 x109/L) compared with CML arising in the adult population (Blood 2012;120:3741) and have a more aggressive course. In addition, the proportion of pediatric patients diagnosed with advanced stage disease, i.e. accelerated phase or blast phase, is higher than seen in adult patients (Blood 2016;127:392). They tend to show a different distribution of the breakpoint region, more similar to that seen in the adult population who develop BCR-ABL+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012;51:1045). They may also have a lower rate of molecular remission with imatinib compared with adult patients, although response with second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be higher and remains under study.

Blast phase is defined as ≥ 20% blasts in the blood or bone marrow or the presence of extramedullary proliferations of blasts. In most of the cases the blasts are myeloid, but in 20-30% of cases they are lymphoblasts. These are predominantly B lymphoblasts, but T and NK blast populations have also been reported (WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Revised 4th Edition, 2017).

In this case, it was also important to differentiate a lymphoid blast crisis arising from CML from B acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL), which also occurs in the pediatric population and can be associated with BCR-ABL1 fusion. However, the t(9;22)(q34.1;q11.2) BCR-ABL fusion is relatively rare in pediatric cases of B-ALL, accounting for only 2-4% of pediatric cases compared with 25% of adult B-ALL (WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Revised 4th Edition, 2017). While there are increased immature myeloid elements in the peripheral blood, this may happen in the setting of any process in which the bone marrow is infiltrated. The presence of the BCR-ABL1 fusion in more differentiated myeloid elements favors CML as the underlying process. Mixed phenotype acute leukemia may also occur de novo or arising from CML. Here, however, there was not an increased myeloid blast population. B-ALL with BCR-ABL1, blast or accelerated phase CML and chronic phase CML all benefit from tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.

Test question answer:

B. Adult patients with CML are more likely to achieve remission with imatinib therapy. Whether children may respond better to second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors is under investigation. Pediatric patients presenting with CML tend to have a higher white blood cell count and are more likely to present in accelerated or blast phase than their adult counterparts. Both populations often present with splenomegaly, but it may be more noticeable in children.