All cases are archived on our website. To view them sorted by case number, diagnosis or category, visit our main Case of the Week page. To subscribe or unsubscribe to Case of the Week or our other email lists, click here.

Thanks to Dr. Raul Gonzalez, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY (USA) for contributing this case and Dr. Belinda Lategan, St. Boniface Hospital, Winnipeg, Manitoba (Canada), for writing the discussion. To contribute a Case of the Week, first make sure that we are currently accepting cases, then follow the guidelines on our main Case of the Week page.

CLINICAL PATHOLOGY

IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM

Keep your clinical pathology skills up to date and meet Maintenance of Certification (MOC) requirements with the Clinical Pathology Improvement Program (CPIP), the online, hands-on, interactive CME course using actual case studies.

Earn up to 15 CME/Self-Assessment Modules (SAMs) this year through 12 intriguing cases delivered right to your desktop. Learn on your schedule - access the program 24/7 and bookmark your place to return later.

Each month, CPIP delivers:

• A case-based challenge, complete with background, images, lab findings, and references.

• Credits to claim. Earn 1.25 CME/SAM credits when you pass each case.

• Convenience. CPIP’s interactive, immediate feedback lets you test your diagnostic skills in real time as you work through an actual case.

• Current, comprehensive content. Keep clinical pathology skills up-to-date; meet American Board of Pathology (ABP) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) requirements.

Try before you buy!

Test your knowledge with one of our most popular CPIP courses - a challenging hematology case involving eosinophilia. Complimentary for a limited time.

Register now

Website news:

(1) Our request this week is for images relevant to:

STAT6 images for Solitary fibrous tumor of colon (or elsewhere)

We believe it is important to have an adequate number of high quality images on our server, because images on other servers often disappear. If you own images of these entities, please email them as attachments to Dr. Nat Pernick at NatPernick@gmail.com, with any corresponding clinical history. There is no payment for image contributions, but we will acknowledge you as contributor, so please indicate how you want your name to be displayed.

(2) Did you know about these other email newsletters we offer for free as well?

• What's New in Pathology: Sent quarterly. Written by members of the PathologyOutlines.com Editorial Board. A new "What's New in Medical Renal Pathology" newsletter is coming out soon.

• Commercial / Promotions: Commercial emails are sent from time to time, but typically no more than monthly, and include a contest to receive an Amazon gift card just for reading the email. Promotions emails are sent before the USCAP and CAP / ASCP meetings, and list special offers for our visitors.

• Jobs, Fellowships and Conferences: Sent biweekly. Lists new postings for Pathologist, PhD and related Jobs, Fellowships, Conferences, CME, Webinars and New Products and Services.

• Website News and New Books: Sent monthly. Lists new and updated features of the website (see Blog) and new books added to the Books pages.

To subscribe to any of these simply go to: http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/subscribe.html and follow the instructions at the bottom of the page. We also post the What's New in Pathology newsletters at the top of this page, so that you can go back and read any you may have missed.

Visit and follow our Blog to see recent updates to the website.

Case of the Week #436

Clinical history:

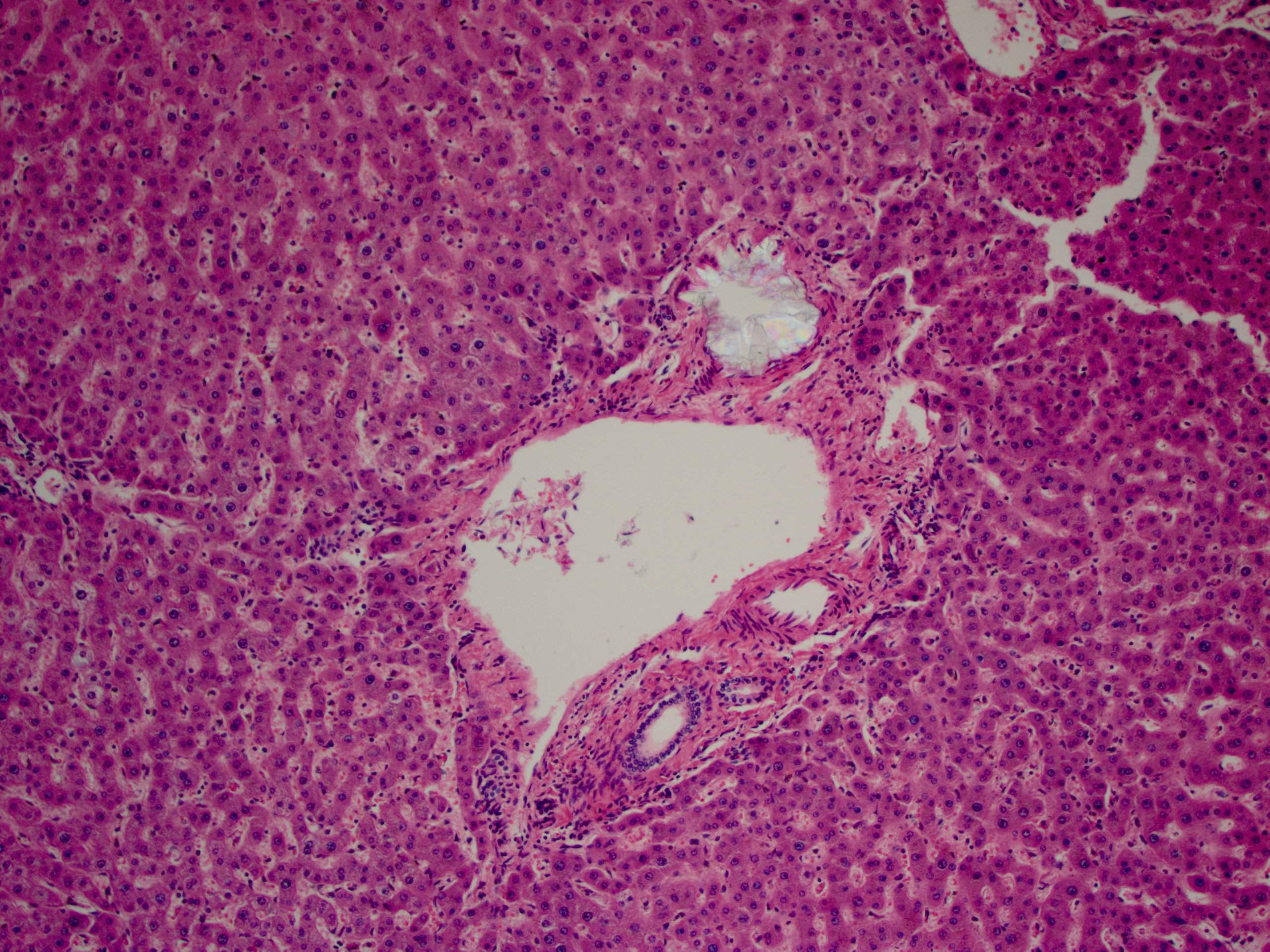

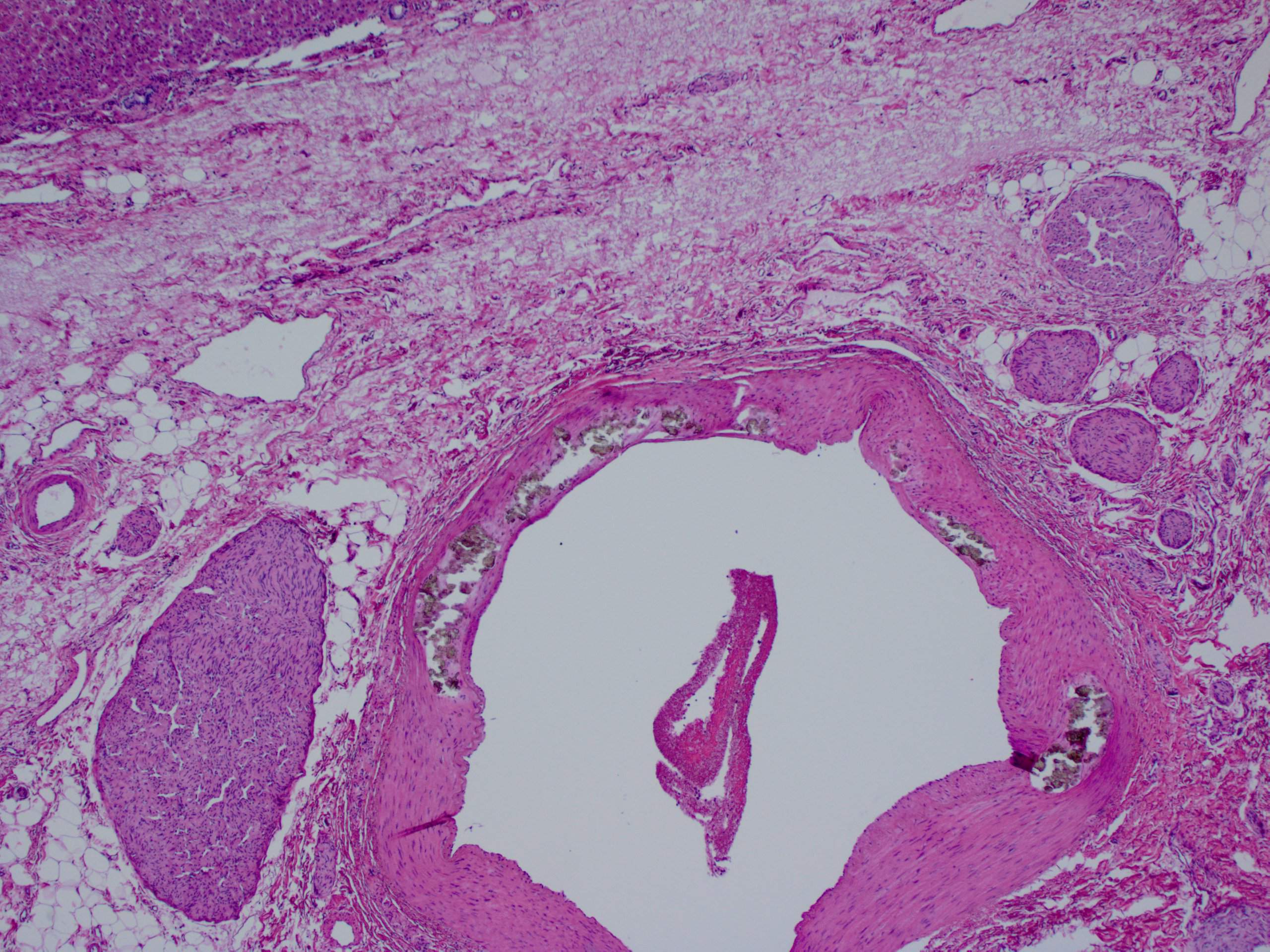

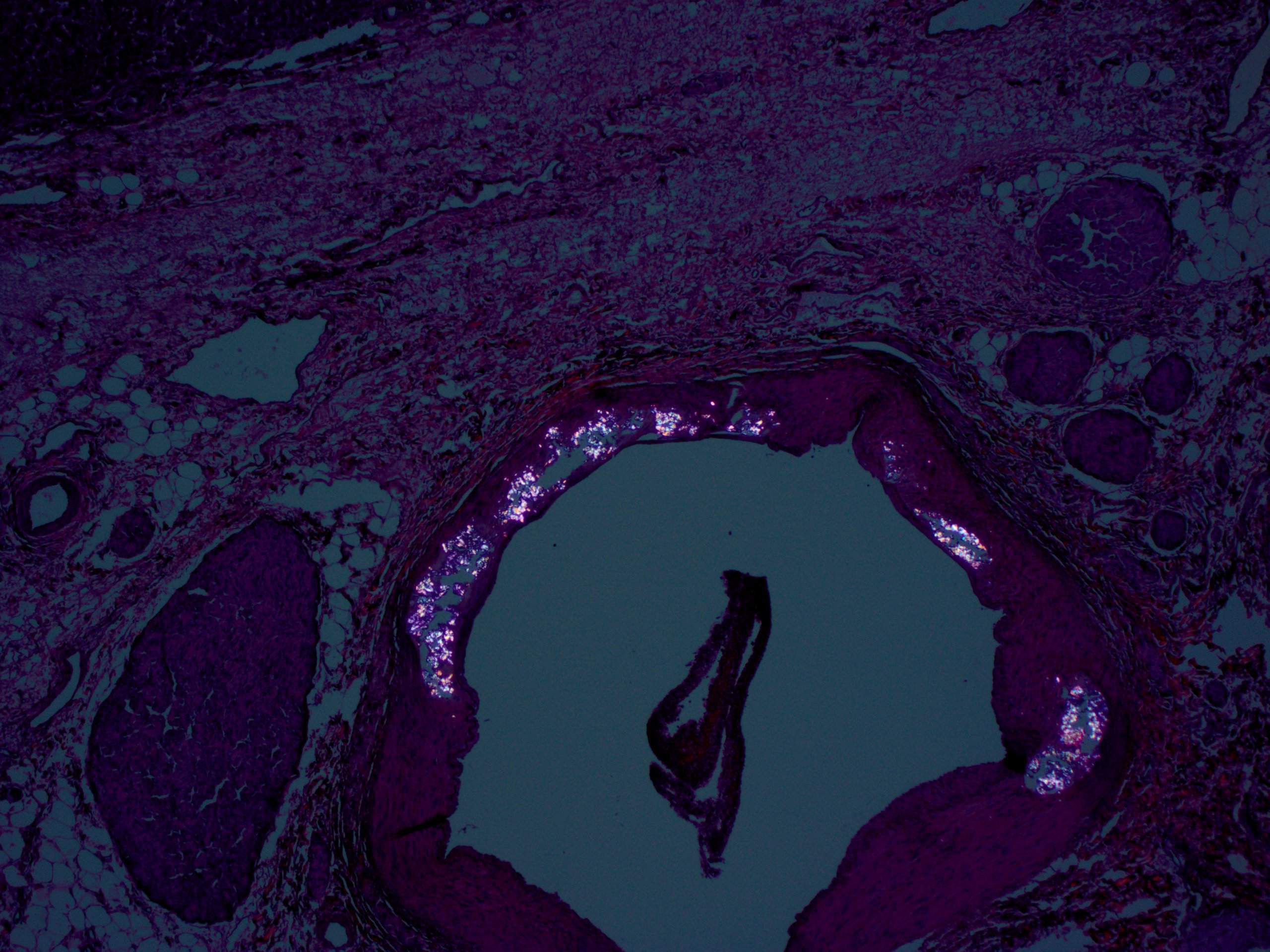

A 30 year old woman with clinical end stage renal disease and end stage liver disease underwent a combined kidney/liver transplant. The microscopic images are from the liver explant.

Histopathology images:

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis:

Primary hyperoxaluria involving the liver

Test question (answer at the end):

The type of kidney and bladder stones most often encountered in primary hyperoxaluria (PH) are:

A. Pyruvate stones

B. Calcium stones

C. Struvite stones

D. Mixed stones

Discussion:

Primary hyperoxaluria (PH) is a rare genetic disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance. Glyoxalate metabolism, which almost exclusively occurs in hepatocytes, is defective and results in excessive oxalate production. Oxalate excretion is almost entirely via the kidneys, predominantly as highly insoluble calcium salts. Oversaturation of the renal tubular filtrate leads to crystallization in the renal tubules, nephrocalcinosis and urolithiasis, often with superimposed infection.

The combination of direct renal tubular toxicity and obstruction results in renal injury with subsequent end stage renal failure in the more severe subtypes. Calcium oxalate deposition in non-renal tissues (systemic oxalosis), including the retina (diminished visual acuity), myocardium (conduction defects), blood vessel walls (vascular occlusion and gangrene), skin (livedo reticularis, calcinosis cutis metastatica, gangrene), bone (pain, joint immobility, anemia, fractures) and central nervous system also occurs (Curr Rheumatol Rep 2013;15:340, N Eng J Med 2013;369).

The three most common subtypes of primary hyperoxaluria are caused by mutations in one of three genes. PH Type 1 affects 80% of patients and demonstrates mutations in the AGXT gene, which encodes for the hepatic peroxismal enzyme alanine: glyoxalate aminotransferase (AGT). The phenotype is heterogeneous, but typically patients with PH type 1 are the most severely affected of the three most common types. PH Type 2, which affects ~10% of patients, has defects in the GRHPR gene, which encodes for GRHPR enzyme. Patients tend to be less severely affected compared to type 1 PH. PH Type 3, ~5% of cases, demonstrates defects in the HOGA1 gene which encodes for the mitochondrial 4-hydroxy-2-oxoglutarate (HOG) aldolase enzyme. A small subset of patients (~5%) with primary hyperoxaluria does not have demonstrable mutations in the any of these three genes (N Engl J Med 2013;369, Int J Nephrol 2011;2011:864580).

Primary hyperoxaluria typically manifests in infancy or childhood with recurring kidney and bladder stones and other symptoms of systemic oxalosis, but some patients are only diagnosed in adulthood. The majority of type 1 and 2 PH patients require ongoing medical treatment. Type 3 PH becomes clinically silent by age 6 years and patients do not typically progress beyond mild renal impairment. In the most severely affected patients, liver transplantation is currently the only cure as this addresses the underlying causative enzyme deficiency, although the organ is otherwise normal. Combined liver and renal transplantation is often necessary due to end stage renal disease in types 1 and 2 PH. Renal transplantation without concomitant liver transplantation is associated with a higher rate of transplant failure due to recurrent oxalate induced renal injury (N Engl J Med 2013;369, Int J Nephrol 2011;2011:864580, Curr Rheumatol Rep 2013;15:340).

A diagnosis of primary hyperoxaluria suspected on clinical and biochemical grounds can be confirmed with genetic testing for the most common gene mutations (AGXT, GRHPR and HOGA1). Antenatal and preimplantation diagnosis is possible in affected families. Prior to the availability of genetic testing, liver biopsy was required to demonstrate AGT deficiency in PH type 1. Immunoblot assays allow analysis of the protein and immunoelectron examination illustrates the near absence of AGT in peroxisomes.

Findings in explanted livers, such as in this case, include birefringent oxalate crystals in vessel walls and connective tissues of the portal areas (Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002;126:1250). Oxalate crystals may also be seen in organs of patients with secondary hyperoxalosis, including enteric hyperoxaluria and ethylene glycol poisoning (Curr Rheumatol Rep 2013;15:340).

Test Question Answer:

B. Calcium stones. Oxalate excretion is almost entirely via the kidneys, predominantly as highly insoluble calcium salts.

Additional References:

Niaudet, P.: UpToDate, Primary hyperoxaluria, 2017